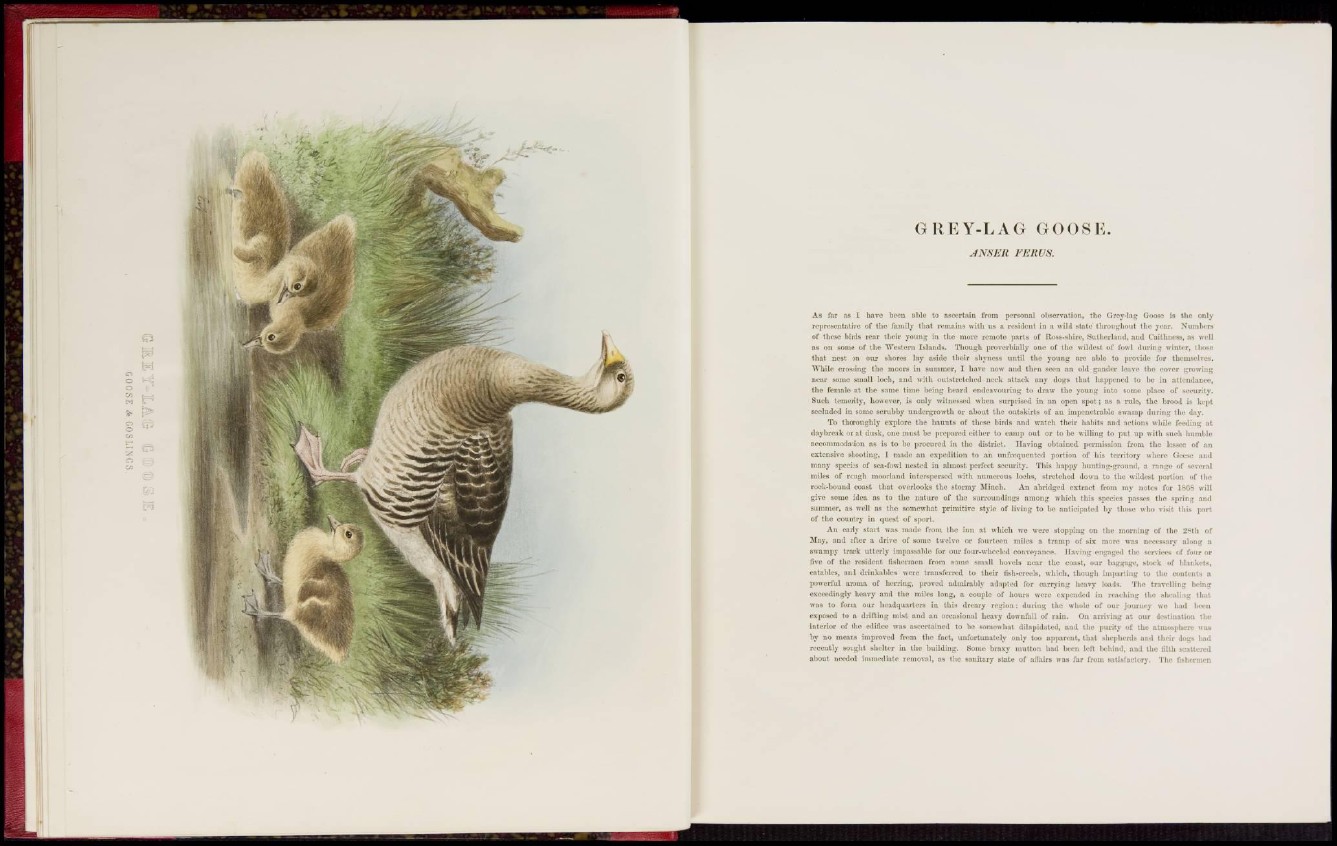

G R E Y - L A G G O O S E.

JNSER FERUS.

As far as I have been able, to ascertain from personal observation, the Grey-lag Goose ia the only

representative or the family that remains with us a resident in a wild slate thru ugh out the year. Numbers

of these birds rear their young in the more remote parts of Ross-shire, Sutherland, and Caithness, as well

as on some of the Western Islands. Though proverbially one of the wildest of fowl during winter, IhoM

that nest on our shores lay aside their shyness until the young He able to provide for themselves.

While crossing the moors in summer, I have now and then Men an old gander leave tlio cover growing

near some small loch, and with outstretched neck attack any dogs that happened to be in attendance,

the female at the same time being heard endeavouring to draw the young into some place of security.

Such temerity, however, is only witnessed when surprised in an open spot; as a rule, the brood is kept

secluded in some scrubby undergrowth or about the outskirts of an impenetrable swamp during the day.

To thoroughly explore the haunts of these bird* and watch their habits and actions while feeding at

daybreak or at dusk, one must bo prepared either to camp out or to be willing to put up with such humble

accommodation as is to he procured in the district. Having obtained permission from the lessee of an

extensive shooting, I made an expedition to an unfrequented portion of his territory where Geese and

many species of sea-fow[ nested in almost perfect security. This happy hunting-ground, a raagc of several

miles of rough moorland interspersed with numerous loehs, stretched down to the wildest portion of the

rock-bound, coast that overlooks the stormy Miueh. An abridged extract from my notes for 18CS will

give some idea as to the nature of the surroundings among which this tpeeiei passes the spring and

summer, as well as the somewhat primitive style of living to he anticipated by those who visit this part

of the country in quest of sport.

An early start was made from the inn at which we were stopping on the morning of the 2Sth of

May, and after a drive, of some twelve or fourteen miles a tramp of six more was necessary along a

swampy track utterly impassable for our four-wheeled conveyance. Having engaged the services of four or

five of the resident fishermen from sumo small hovels near the coast, our baggage, stock of blankets,

eatables, and drinkables were transferred to their fish-ereels, which, though imparting to the contents a

powerful aroma of herring, proved admirably adapted for carrying heavy loads. The travelling being

exceedingly heavy and the miles long, a couple of hours were expended in reaching the shoaling that

was to form our headquarters in this dreary region: during the whole of our journey we had been

exposed to a drifting mist and an occasional heavy downfall of rain. On arriving at our destination the

interior of the edifice was ascertained to be somewhat dilapidated, and the purity of the atmosphere was

by no means improved from the fact, unfortunately only too apparent, that shepherds and their dogs had

recently sought shelter in the building. Some hraxy mutton bad been left behind, and the tilth scattered

about needed immediate removal, as the sanitary state of alfairs was far from satisfactory. The fishermen