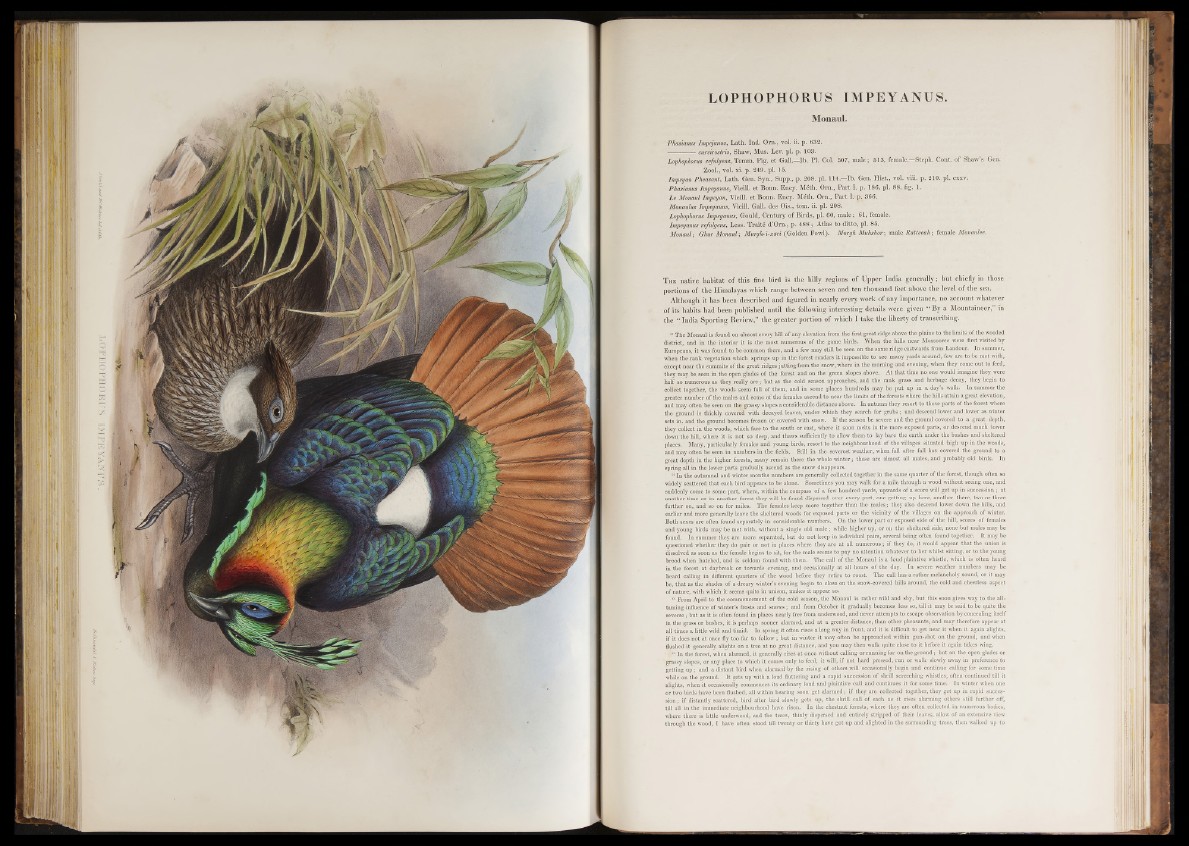

LOPHOPHORUS IMPEYANUS.

Monaul.

Phasianus Impejanus, Lath. Ind. Om., vol. ii. p. 632.

------------- curvirostris, Shaw, Mus. Lev. pi. p. 103.

Lophophortis' refulgens, Temm. Pig. e t Gall.—Ib. PI. Col. 507, male; 513, female.—Steph. Cont. o f Shaw’s Gen.

Zool., vol. xi. p. 249. pl. 15.

Impeyan Pheasant, Lath. Gen. Syn., Supp., p. 208. pi. 114.—Ib . Gen. H ist., vol. viii. p. 210. pi. cxxv.

Phasianus Impeyanus, Vieill. e t Bonn. Ency. Méth. Orn., P a rt I. p. 186. pi. 88. fig. 1.

Le Monaul Impeyan, Vieill. e t Bonn. Ency. Méth. Orn., P a rt I.' p.^ 366.

Monaulus Impeyanus, Vieill. Gall, des Ois., tom. ii. pi. 208.

Lophophortis Impeyanus, Gould, Century of B irds, pi. 60, male; 61, female.

Impeyanus refulgens, Less. T ra ité d’Om., p. 488 ; Atlas to ditto, pi. 85.

Monaul; Ghur Monaul-, Murgh-i-zari (Golden Fowl). Murgh Muhshor-, male Ratteeah; female Monaulee.

T he native habitat o f this fine bird is the hilly regions of Upper India generally ; but chiefly in those

portions of the Himalayas which range between seven and ten thousand feet above the level of the sea.

Although' it has been described and figured in nearly every work of any importance, no account whatever

of its habits had been published until the following interesting details were given “ By a Mountaineer,” in

the “ India Sporting Review,” the greater portion of which I take the liberty of transcribing.

" The Monaul is found on almost every hill of any elevation from the first great ridge above the plains to. thè limits of the wooded

district, and in the interior it is the most numerous of the game birds. When the hills near Mussooree were first visited by

Europeans, it was found, to be common there, and a few may still be seen on the same ridge eastwards from Landour. In summer,

when the rank vegetation which springs up in the forest renders it impossible to see many yards around, few are to be met with,

except near the summits of the great ridges jutting from the show, where in thè morning and evening, when they come out to feed,

they may be seen in the open glades of thé forest and; on the green slopes above. At that time no one would imaginé they were

half so numerous as they really are; but as the cold season approaches, and the rank grass and herbage decay, they begin to

collect together, the woods seem full of them, and in some places hundreds may be. put up in a day’s walk. In summer the

greater number of the males and some of the females ascend to near the limits of the forests where the hills attain a great elevation,

and may often be seen on thé grassy slopes a considerable distance above. In autumn they resort to those parts of the forest where

..the ground is thickly coverei with decayed leaves, under which they search for grubs ; and descend lower and lower as winter

sets in, and the ground becomes frozen or covered with snow. If the season be severe and the ground covered, to a great depth,

they collect in the woods, which face to the south or east, where it soon melts in the more exposed parts, or descend much lower

down the hill, where it is not so deep, and thaws sufficiently to allow them to lay bare the earth under the bushes and sheltered

plaCes. Many, particularly females and young birds, resort to the- neighbourhood of. the villages situated high up in the.woods,

and may often be seen in numbers in the fields. Still in the severest weather, when fall after fall has covered the ground to a

great depth in the higher forests, many remain there the whole winter ; these are almost all males, and probably old birds. In

spring all in the lower parts gradually ascend as the snow disappears.

“ In the autumnal and winter months numbers are generally collected together in the same quarter of the forest, though often so

widely scattered that each bird appears to be alone. Sometimes you may walk for a mile through a wood without seeing one, and

suddenly come to some part, where, within the compass of a few hundred yards, upwards of a score will get up in succession ; at

another time or in another forest they will be found dispersed over every part, one getting up here, another there, two or three

further on, and so on for miles. The females keep more together than the males ; they also descend lower down the hills, and

earlier and more generally leave the sheltered woods for exposed parts or the vicinity of the villages on the approach of winter.

Both sexes are often found separately in considerable numbers. On the lower part or exposed side of the hill, scores of females

and young birds may be met with, without a single old male ; while higher up, or on the sheltered side, none but males may be

found. In summer they are more separated, but do not keep in individual pairs, several being often found together. It may be

questioned whether they do.pair òr not in places where they are at all numerous; if they do, it would appear that the union is

dissolved as soon as the female begins to sit, for the male seems to pay no attention whatever to her whilst sitting, or to the young

brood when hatched, and is seldom found with them. The call of the Monaul is a loud plaintive whistle, which is’ often heard

in the forest at daybreak or towards evening, and occasionally at all hours of the day. In severe weather numbers may be

heard calling in different quarters of the wood before they retire to roost. The call has a rather melancholy, sound, or it may

be, that as the shades of a dreary winter’s evening begin to close on the snow-covered hills around, the cold and- cheerless aspect

of nature, with which it seems quite in unison, makes it appear so.

“ From April tò the commencement of the cold season, the Monaul is rather wild and shy, but this soon gives way to the alltaming

influence of winter’s frosts and snows ; and from October it gradually becomes less so, till it may be said to be quite the

reverse ; but as it is often found in places nearly free from underwood, and never attempts to escape observation by concealing itself

in the grass or bushes, it is perhaps sooner alarmed, and at a greater distance, than other pheasants, and may therefore appear at

all times a little wild and timid. In spring it often rises a long way in front, and it is difficult to get near it when it again alights,

if it does not at once fly too far to follow ; but in winter it may often be approached within gun-shot on the ground, and when

flushed it generally, alights on a tree at no great distance, and you may then walk quite close to it: before it again takes wing.

In the forest, when alarmed, it generally rises at once without calling or running far on the ground; but on the open glades or

grassy slopes, or any place to which it comes only to feed, it will, if not hard pressed, run or walk slowly away in preference to

getting up ; and a distant bird when alarmed by the rising of others will occasionally begin and continue calling for some time

while on the ground. It gets up with a loud fluttering and a rapid succession of shrill screeching whistles, often continued till it

-alights, when it occasionally commences its ordinary loud and plaintive call and continues it for some time. In winter when one

or two birds have been flushed, all within hearing soon get alarmed ; if they are collected together, they get up in rapid succession

; if distantly scattered, bird after bird slowly gets up, the shrill call of each as it rises alarming others still further off,

till all in the immediate neighbourhood have risen. In the chestnut forests, where they are often collected in numerous bodies,

where there is little underwood, and the trees, thinly dispersed and entirely stripped of their leaves, allow of an extensive view

through the wood, I have often stood till twenty or thirty have got up and alighted in the surrounding trees, then walked up to