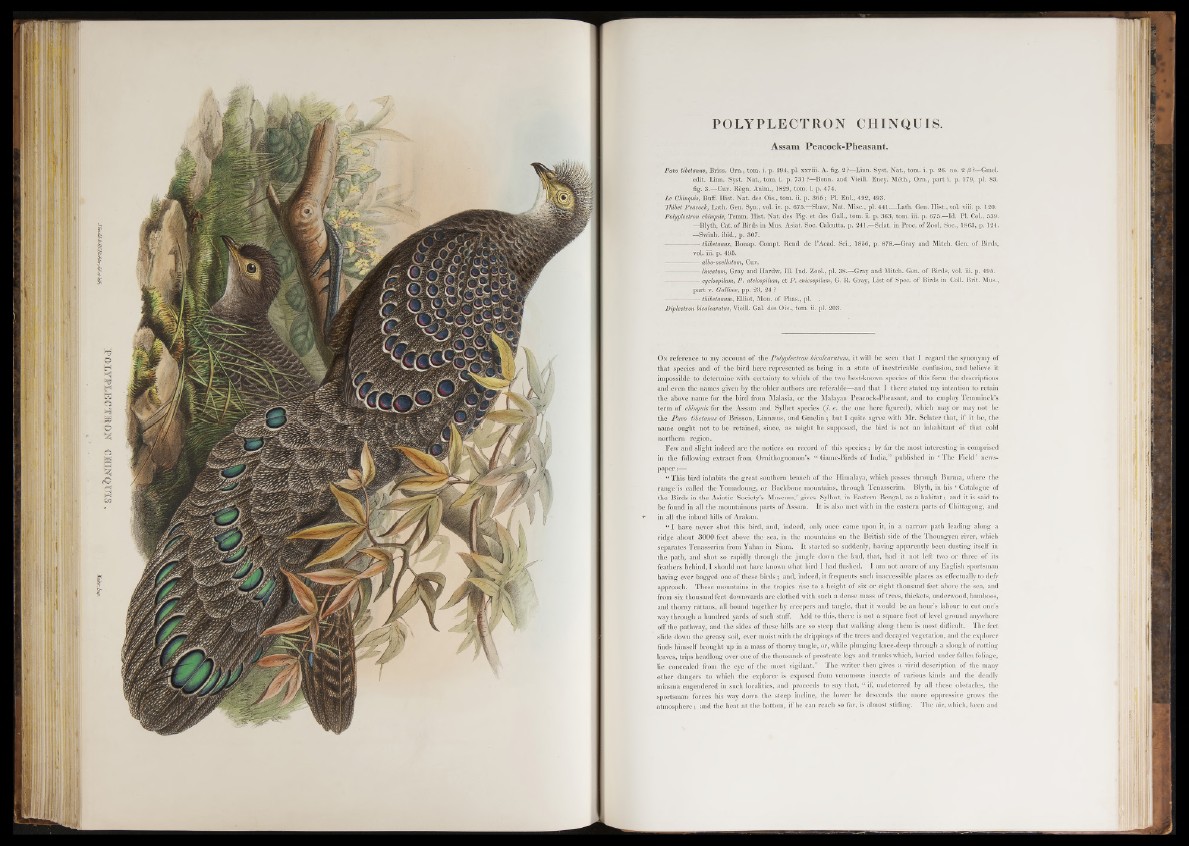

POLYPLECTRON CHINQUIS.

Assam Peacock-Pheasant.

Pavo tibetanus, Briss. Om., tom. i. p. 294, pi. xxviii. A. fig. 2 ?—Linn. Syst. Nat., tom. i. p. 26. no. 2 /3 ?—Gmel.

edit. Linn. Syst. Na t., tom. i. p. 731 ?—Bonn, and Vieill. Ency. Meth., Orn., p a r ti , p . 179, pi. 83.

fig. 3.—Cuv. Regn. Anim., 1829, tom. i. p. 474.

Le Chinquis, Buff. Hist. N a t. des Ois., tom. ii. p. 365 ; PI. Enl., 492, 493.

Thibet Peacoclc, Lath. Gen. Syn., vol. iv. p . 675.—Shaw, Nat. Misc., pi. 441 Lath. Gen. Hist., vol. viii. p. 120.

Polyplectron chinquis, Temm. Hist. Na t. des Pig. e t des Gall., tom. ii. p. 363, tom. iii. p. 675.—Id. PI. Col., 539.

—Blyth, Cat. o f Birds in Mus. Asiat. Soc. Calcutta, p. 241.—Sclat. in Proc. of Zool. Soc., 1863, p. 124.

—SwinH.' ibid.,, p. 307.!

— thibetanus, Bonap. Compt. Rend de l’Acad. Sci., 1856, p. 878.—Gray and Mitch. Gen. of Birds,

vol. iii. p. 495.

albo-ocelldtum, Cuv.

— lineatum, Gray and Hardw. 111. Ind. Zool., pi. 38.—Gray and Mitch. Gen. o f Birds, vol. iii. p. 495.

— cyclospikm, P. atelospilum, e t P. enicospilum, G. R. Gray, L is t of Spec, o f Birds in Coll. Brit. Mus.,

p a r t v. Gallince, pp. 23, 24 ? — thibetanum, Elliot, Mon. of Phas., pi. .

Diplectron bicalcaratus, Vieill. Gal. des Ois., tom. ii. pi. 203.

On reference to my account of the Polyplectron bicalcaratum, it will he seen that I regard the synonymy of

that species and of the bird here represented as being in a state of inextricable confusion, and believe it

impossible to determine with certainty to which of the two best-known species of this form the descriptions

and even the names given by th e ‘older authors are referable—and that I there stated my intention to retain

the above name for the bird from Malasia, or the Malayan Peacock-Pheasant, and to employ Temminck’s

term o f chinquis for the Assam and Sylhet species (i. e. the one here figured), which may or may not be

the P aw tibetanus of Brisson, Linnseus, and Gmelin ; but I quite agree with Mr. Sclater that, if it be, the

name ought not to be retained, since, as might be supposed, the bird is not an inhabitant of that cold

northern region.

Few and slight indeed are the notices on record of this species; by far the most interesting is comprised

in the following extract from Ornithognomon’s “ Game-Birds o f India,” published in 1 The Field ’ news-

PaPer :~

“ This bird inhabits the great southern branch of the Himalaya, which passes through Burma, where the

range is called the Yomadoung, or Backbone mountains, through Tenasserim. Blyth, in his ‘ Catalogue of

the Birds in the Asiatic Society’s Museum,’ gives Sylhut, in Eastern Bengal, as a h ab ita t; and it is said to

be found in all the mountainous parts of Assam. I t is also met with in the eastern parts of Chittagong, and

in all the inland hills of Arakan.

“ I have never shot this bird, and, indeed, only once came upon it, in a narrow path leading along a

ridge about 3000 feet above the sea, in the mountains on the British side of the Thoungyen river, which

separates Tenasserim from Yahan in Siam. It started so suddenly, having apparently been dusting itself in

the path, and shot so rapidly through the jungle down the kud, that, had it not left two or three o f its

feathers behind, I should not have known what bird I had flushed. I am not aware o f any English sportsman

having ever bagged one o f these bird s; and, indeed, it frequents such inaccessible places as effectually to defy

approach. These mountains in the tropics rise to a height o f six or eight thousand feet above the sea, and

from six thousand feet downwards are clothed with such a dense mass of trees, thickets, underwood, bamboos,

and thorny rattans, all bound together by creepers and tangle, that it would be an hour’s labour to cut one’s

way through a hundred yards of such stuff. Add to this, there is not a square foot o f level ground anywhere

off the pathway, and the sides o f these hills are so steep that walking along them is most difficult. The feet

slide down the greasv soil, ever moist with the drippings of the trees and decayed vegetation, and the explorer

finds himself brought up in a mass of thorny tangle, or, while plunging knee-deep through a slough- o f rotting

leaves, trips headlong over one of the thousands of prostrate logs and trunks which, buried under fallen foliage,

lie concealed from the eye of the most vigilant.” The writer then gives a vivid description o f the many

other dangers to which the explorer is exposed from venomous insects of various kinds and the deadly

miasma engendered in such localities, and proceeds to say that, “ if, undeterred by all these obstacles, the

sportsman forces his way down the steep incline, the lower he descends the more oppressive grows the

atmosphere; and the heat at the bottom, if he can reach so far, is almost stifling. The air, which, keen and