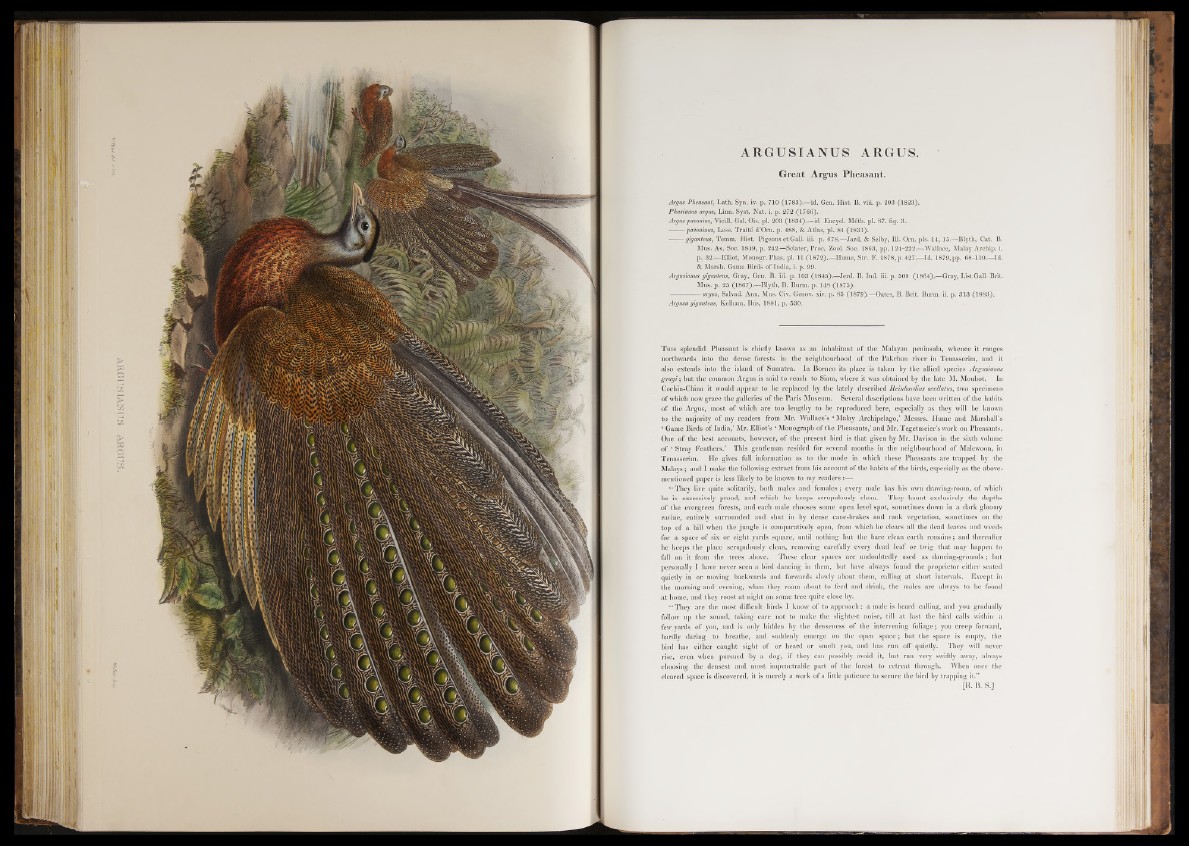

ARGUSIANUS ARGUS.

Great Argus Pheasant.

Argus Pheasant, Lath. Syn. iv. p. 710 (1783).—id; Gen. Hist. B. viii. p. 203 (1823).

Phasianus argus, Linn. Syst. N a t. i. p. 272 (1766).

Argus pavonius, Vieill. Gal. Ois. pi. 203 (1834).—id. Encycl. Méth. pi. 87. fig. 3.

pavoninus, Less. Tra ité d’Om. p. 488, & Atlas, pi. 84 (1831).

giganteus, Temm. Hist. Pigeons e t Gall. iii. p. 678.—Jard . & Selby, 111. Orn. pis. 14, 15.— Blyth, Cat. B.

Mus. As. Soc. 1849, p. 242.—Sclater, Proc. Zool. Soc. 1863, pp. 124-222.-—Wallace, Malay Archip. i.

p . 32.—Elliot, Monogr. Phas. pi. 11 ('1872).— Hume, Str. F. 1878, p. 427.—Id . 1879, pp. 68-110.—Id.

& Marsh. Game Birds of India, i. p. 99.

Argusianus giganteus, Gray, Gen. B. iii. p. 103 (1845).—Jerd. B. Ind. iii. p. 509 (1864).—Gray, L ist Gall. Brit.

Mus. p. 25 (1867).—Blyth, B. Burm. p. 148 (1875).

— argus, Salvad. Ann. Mus. Civ. Genov, xiv. p. 85 (1879).—Oates, B. Brit. Burm. ii. p . 313 (1883).

Argusa giganteus, Kelham, Ibis, 1881, p. 530.

T his splendid Pheasant is chiefly known as an inhabitant of the Malayan peninsula, whence it ranges

northwards into the dense forests in the neighbourhood of the Pakchan river in Teuasserim, and it

also extends into the island of Sumatra. In Borneo its place is taken by the allied species Argusianus

g ra y i; but the common Argus is said to reach to Siam, where it was obtained by the late M. Mouhot. In

Cochin-China it would appear to be replaced by the lately described Reinhardius ocellatus, two Specimens

o f which now grace the galleries of the Paris Museum. Several descriptions have been written of the habits

of the Argus, most o f which are too lengthy to be reproduced here, especially as they will be known

to the majority of my readers from Mr. Wallace’s ‘Malay Archipelago,’ Messrs. Hume aud Marshall’s

* Game Birds of India,’ Mr. Elliot’s ‘ Monograph of the Pheasants,’ and Mr. Tegetmeier’s work on Pheasants.

One of the best accounts, however, o f the present bird is that given by Mr. Davison in the sixth volume

o f ‘ Stray Feathers.’ This gentleman resided for several months in the neighbourhood of Malewoon, in

Tenasserim. He gives full information as to the mode in which these Pheasants are trapped by the

Malays; and I make the following extract from his account of the habits of the birds, especially as the above-

mentioned paper is less likely to be kuown to my readers :—

“ They live quite solitarily, both males and females; every male has his own drawing-rootn, o f which

he is excessively proud, and which he keeps scrupulously clean. They haunt exclusively the depths

of th,e evergreen forests, and each male chooses some open level spot, sometimes down in a dark gloomy

ravine, entirely surrounded and shut in by dense cane-brakes and rank vegetation, sometimes on the

top o f a hill when the jungle is comparatively open, from which he clears all the dead leaves and weeds

for a space o f six or eight yards square, until nothing but the bare clean earth remains; and thereafter

he keeps the place scrupulously clean, removing carefully every dead leaf or twig that may happen to

fall on it from the trees above. These clear spaces are undoubtedly used as dancing-grounds; but

personally I have never seen a bird dancing in them, but have always found the proprietor either seated

quietly in or moving backwards and forwards slowly about them, calling at short intervals. Except in

the morning and evening, when they roam about to feed and drink, the males are always to be found

at home, and they roost a t night on some tree quite close by.

“ They are the most difficult birds I know of to approach: a male is heard calling, and you gradually

follow up the sound, taking care not to make the slightest noise, till at last the bird calls within a

few.yards of you, and is only hidden by the denseness of the intervening foliage; you creep forward,

hardly daring to breathe, and suddenly emerge on the open space; but the space is empty, the

bird has either caught sight of or heard or smelt you, and has run off quietly. They will never

rise, even when pursued by a dog, if they can possibly avoid it, but run very swiftly away, always

choosing the densest and most impenetrable part of the forest to retreat through. When once the

cleared space is discovered, it is merely a work of a little patience to secure the bird by trapping it.”

[R. B. S.]