I T O S C H ’E I A t U A B K L

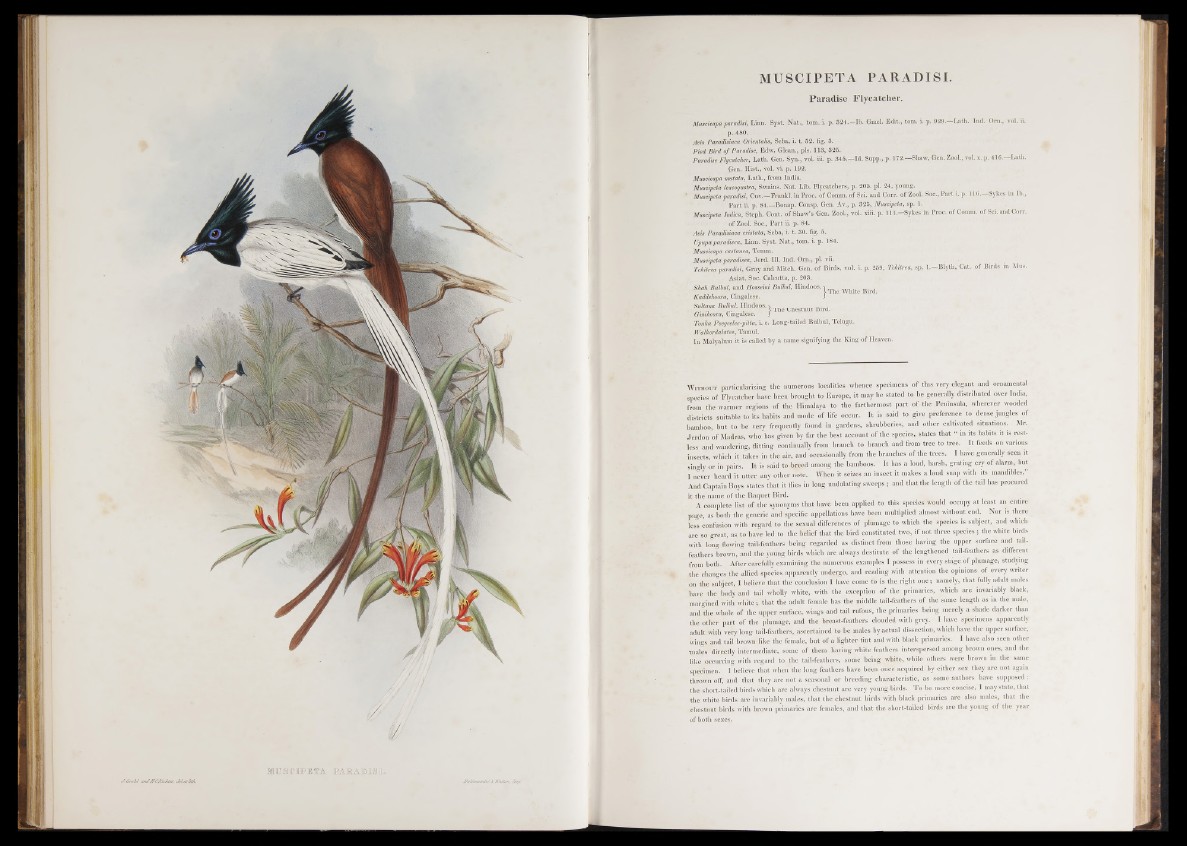

MUSCIPETA PARADISI.

Paradise Flycatcher.

Muscicapaparaim, Linn. Syst. Nat., tom. i. p. 324.- I b . Gmd. Edit., tom. i. p. 929.—Lath. Ind. Ora., vol. ii.

p . 480.

Avis Paradisiaca Orientalis, Seba, i. t. 52. fig. 3.

Pied Bird o f Paradise, Edw. Glean., pis. 113, 325.

Paradise Flycatcher, Lath. Gen. Syn., vol. iii. p. 345.—Id. Supp., p. 172.—Shaw, Gen. ZooL, vol. x. p. 416—Lath.

pen. Hist., vok vi. p. 192.

Muscicapa mutata, Lath., from India.

Muscipeta leucogastra, Swains. Nat. Lib. Flycatchers, p.. 205. pi. 24, young.

■ Muscipeta paradisi, Cuv.—Frankl. inProc. of Comm, of Sci. and Corr. of Zool. Soc., Part i. p. 116. Sykes in lb.,

Part ii. p. 84.—Bonap. Consp. Gen. Ay., p. 325, Muscipeta, sp. 1.

Muscipeta Indies, Steph. ConL of Shaw’s Gen. Zool, vol. xiii. p. 111.—Sykes' in Pi oc. -of Comm, of Sci. and Corr.

of Zool. Soc., Part ii. p. 84.

Avis Paradisiaca cristata, Seba, i. t. 30. fig. 5.

Upupa paradisea, Linn. Syst. Nat., tom. i. p. 184.

Muscicapa castanea, Temm.

Muscipeta paradisea, Jerd. 111. Ind. Orn., pi. Yii.

Tcldlrea paradisi, Gray and Mitch-Gen. of Birds, vol. I. p. 259, Tshitrea, sp. 1.—Blyih, Cat. of Birds in Mus.

Asiat. Soc. Calcutta, p. 203.

Shah Bulbul, and Hosseini Bulbul, Hindoos. -» ,

■M HM H h h I ! > The White Bird.

Kaddehoora, Cingalese. J

Sultana Bulbul, H, indops.I ■ T» he Chestnut ^B ird.,

Ginihoora, Cingalese. J

Tonka Peegeelee-pitta, i. e. Long-tailed Bulbul, Telugu.

Walkordalatee, Tatnul.

In Malyalum it is called by a name signifying the King of Heaven.

W it h o u t particularizing the numerous localities whence specimens o f this very elegant and ornamental

species of Flycatcher have been brought to Europe, it may be stated to be generally distributed over India,

from the warmer regions :of the Himalaya to the farthermost part of the Peninsula, wherever wooded

districts suitable to its habits and mode of life occur. I t is said to give preference to dense juDgles of

bamboo, but to be very frequently found in gardens, shrubberies, and other cultivated situations. Mr.

Jerdon of Madras, who has given by far the best account of the species, .states th a ti||in its habits it is restless

and wandering, flitting continually from branch | | branch and from tree to tree. It feeds on various

insects, Which it takes in the air, and occasionally from the branches of the trees. I have generally seen it

singly or in pairs. I t is-said to hgted among the bamboos: It has a loud, harsh, grating cry of alarm, hut

I never'heard it utter any other note. When it seizes an insect it makes a loud snap with its mandibles.’?

And Captain Boys states that it flies in long undulating sweeps; and that the length of the tail has procured

it-the name of the Raquet Bird.

A complete list of the synonyms that have been applied to this species would occupy a t least an entire

page, as both the generic and specific appellations have been multiplied almost without end. Nor is there

less confusion with regard to the sexual differences of plumage to which the species is subject, and which

are so great, as to have led to the belief that the bird constituted two, if not three species; the white birds

with long flowing tail-feathers being regarded as distinct from those having the upper surface and tail-

feathers brown, and the young birds which are always destitute of the lengthened tail-feathers as different

from both. After carefully examining the numerous examples I possess in every stage o f plumage, studying

the changes the allied species apparently undergo, and reading with attention the opinions of every writer

on the subject, I beiieve that the conclusion I have come to is the right one; namely, that fully adult males

have the body and tail wholly white, with the exception of the primaries, which are invariably black,

margined with white ; th at the adult female has the middle tail-feathers of the same length as in the male,

and. the whole of the upper surface, wings and tail rufous, the primaries being merely a shade darker than

the other p art of the plumage, and the breast-feathers clouded with grey. I have specimens apparently

adult with very long tail-feathers, ascertained to be males by actual dissection, which have the upper surface,

wings and tail brown like the female, but of a lighter tint and with black primaries. I have also seen other

•males directly intermediate, some of them having white feathers interspersed among brown ones, and the

like ^occurring with regard to the tail-feathers, some being white, while others were brown in the same

specimen. I believe that when the long feathers have been once acquired by either sex they are not again

thrown off, and that they are not a seasonal or breeding characteristic, as some authors have supposed :

the short-tailed birds which are always chestnut are very young birds. To be more concise, I may state, that

the white birds are invariably males, that the chestnut birds with black primaries are also males, that the

chestnut birds with brown primaries are females, and that the short-tailed birds are the young of the year

of both sexes.