MALURUS MELANOCEPHALUS, Vig. and Horsf.

Black-headed Wren.

Scarlet-backed Warbler, Lewin, Birds of New Holl., pi. xiv.

Malar us melanocephalus, Vig. and Horsf. in Linn. Trans., vol. xv. p. 222.

Malurus Brownii, Jard. and Selb., 111. Om., vol. ii. pi. 72. fig. 1.

I n their “ Illustrations o f Ornithology,” Sir William Jardine and Mr. Selby have in a very laudable manner

endeavoured to clear up what they considered some confusion respecting the present and the preceding

species, M. Brownii. These gentlemen have, however, fallen into error in considering the two birds as

identical, whereas they are, in fact, totally distinct.

I have never seen the Black-headed Wren from any other locality than New South Wales, and I am.

consequently led to believe that the south-eastern portion of Australia is its peculiar and limited habitat.

It is a local species, not being generally diffused over the face of the country, like several other members

of the group, but confined to grassy ravines and gullies, particularly those that lead down from the

mountain ranges. I obtained several pairs of adult birds in very fine plumage in the valleys under the

Liverpool range, all of which I discovered among the high grasses which there abound; but as the period

o f my visit was that o f their breeding-season, I never observed more than a pair together, each pair being

always stationed at some distance from the other, and in such parts o f the gullies as were studded with

small clumps of scrubby trees.

The Black-headed Wren has many actions in common with the M. cyaneus, and like that species carries

its tail erect: it also frequently perches on a stem of the most prominent grasses, where it displays its

richly-coloured back, and pours forth its simple song. I did not succeed in finding the nest, although I

knew they were breeding around me: it was probably placed among the grasses, but was so artfully

concealed that it completely baffled my efforts at finding it.

One might suppose the-greater development of feather on the back of this species to have been given

it as a defence against the damp and dense grasses of the ravines, among which it usually resides; but from

the circumstance of the female not possessing this character of plumage, and the rich garb being only seasonal

in the male, this supposition falls to the ground. In their winter dress the sexes very nearly

resemble each other; but the males may always he distinguished by the black colouring of the bill and tail-

feathers. The young male o f the year has the tail-feathers brown, like the females, and it is a curious fact,

that at this age these feathers are much longer than in the adult.

The flight o f this species is feeble and not protracted; but, on the contrary, its powers of running and

creeping are very considerable.

The breeding-season probably commences in September and continues until January; its food is insects

of various kinds.

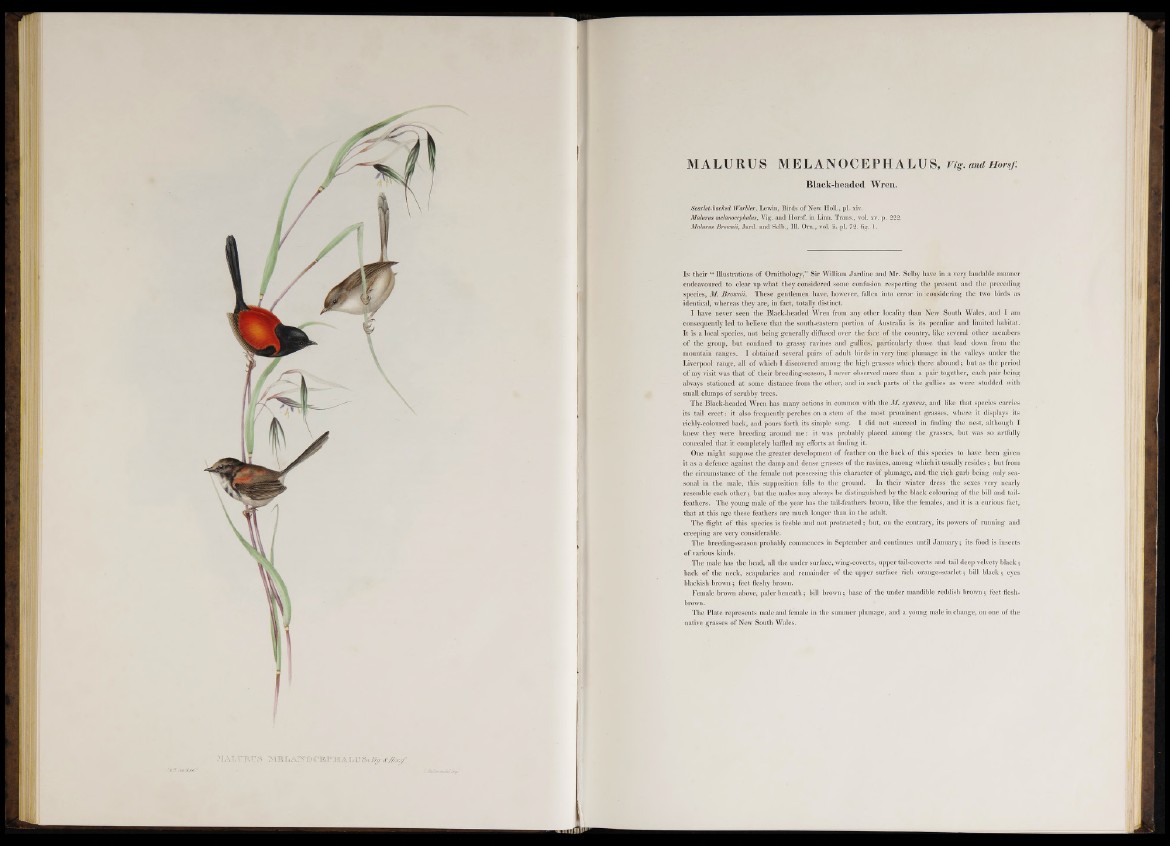

The male has the head, all the under surface, wing-coverts, upper tail-coverts and tail deep velvety black;

back of the neck, scapularies and remainder of the upper surface rich orange-scarlet; bill black; eyes

blackish brown ; feet fleshy brown.

Female brown above, paler beneath; bill brown; base of the under mandible reddish brown; feet flesh-

brown.

The Plate represents male and female in the summer plumage, and a young male in change, on one of the

native grasses o f New South Wales.