M A M m r a C T A B K T IJS . fleill.-

CffuMmtaulei

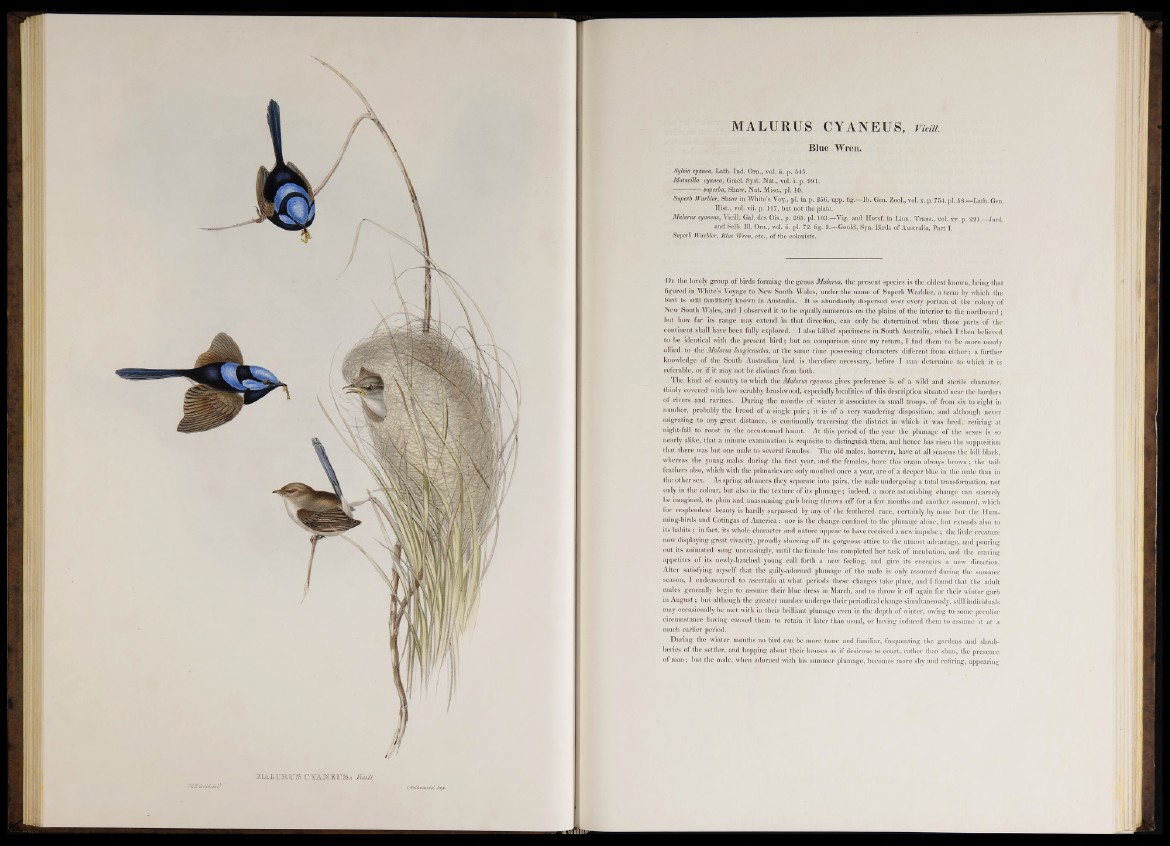

MALURUS CYANEUS, Vieill.

Blue Wren.

Sylvia cyanea, Lath. Ind. Om., vol. ii. p. 545.

Motacilla cyanea, Gmel. Syst. Nat., vol. i. p. 991.

—--------— superha, Shaw, Nat. Misc., pi. 10.

Superb Warbler, Shaw in White’s Voy., pi. in p. 256, upp. fig.—lb. Gen. Zool., vol. x. p. 754. pi. 58.—Lath. Gen.

Hist., vol. vii. p. 117, but not the plate.

Malurus cyaneus, Vieill. Gal. des Ois., p. 265. pi. 163.—Vig. and Horsf. in Linn. Trans., vol. xv. p. 221.—Jard.

and Selb. 111. Ora., vol. ii. pi. 72. fig. 3.—Gould, Syn. Birds of Australia, Part I.

Superb Warbler, Blue Wren, etc., of the colonists.

O f the lovely group of birds forming the genus Malurus, the present species is the oldest known, being that

figured in White’s Voyage to New South Wales, under the name o f Superb Warbler, a term by which the

bird is still familiarly knpwn in Australia. It is abundantly dispersed over every portion o f the colony of

New South Wales, and I observed it to be equally numerous on the plains of the interior to the northward;

but how far its range may extend in that direction, can only be determined when those parts o f the

continent shall have been fully explored. I also killed specimens in South Australia, which I then believed

to be identical with the present bird; but on comparison since my return, I find them to be more nearly

allied to the Malurus longicaudus, at the same time possessing characters different from either; a further

knowledge o f the South Australian bird is therefore necessary, before I can determine to which it is

referable, or if it may npt be distinct from both.

The kind o f country to which the Malurus cyaneus gives preference is of -a' wild and sterile character,

thinly covered with low scrubby brushwood, especially localities o f this description situated near the borders

o f rivers and ravines. During the months o f winter it associates in small troops, o f from six to eight in

number, probably the brood .of a single pair; it is o f a very wandering disposition, and although never

migrating to any great distance, is continually traversing the district in which it was bred, retiring at

night-fall to roost in the accustomed haunt. At this period of the year the plumage o f the sexes is so

nearly alike, that a minute examination is requisite to distinguish them, and hence has risen the supposition

that there was but one male to several females. The old males, however, have at all seasons the bill black,

whereas the young males during the first year, and the females, have this organ always brown; the tail-

feathers also, which with the primaries are only moulted once a year, are o f a deeper blue in the male than in

the other sex. As spring advances they separate into pairs, the male undergoing a total transformation, not

only in the colour, but also in the texture of its plumage; indeed, a more astonishing change can scarcely

be imagined, its plain and unassuming garb being thrown off for a few months and another assumed, which

for resplendent beauty is hardly surpassed by any of the feathered race, certainly by none but the Humming

birds and Cotingas o f America: nor is the change confined to the plumage alone, but extends also to

its habits ; in fact, its whole character and nature appear to have received a new impulse; the little creature

now displaying great vivacity, proudly showing off its gorgeous attire to the utmost advantage, and pouring

out its animated song unceasingly, until the female has completed her task of incubation, and the craving

appetites o f its newly-hatched young call forth a new feeling, and give its energies a new direction.

After satisfying myself that the gaily-adorned plumage of the male is only assumed during the summer

season, I endeavoured to ascertain at what periods these changes take place, and I found that the adult

males generally begin to assume their blue dress in March, and to throw it off again for their winter garb

in August; but although the greater number undergo their periodical change simultaneously, still individuals

may occasionally be met with in their brilliant plumage even in the depth o f winter, owing to some peculiar

circumstance having caused them to retain it later than usual, or having induced them to assume it at a

much earlier period.

During the winter months no bird can be more tame and familiar, frequenting the gardens and shrubberies

of the settler, and hopping about their houses as if desirous to court, rather than shun, the presence

of man; but the male, when adorned with his summer plumage, becomes more shy and retiring, appearing