DESCRIPTION.

The Dog has short conical ears like the American wolf, but its nose is still shorter than that

of the latter animal. Its nose, cheeks, belly, and legs, are white. The fore-legs are destitute

of the black mark above the wrist, which characterises the European wolf, and which is visible,

in some American wolves, but not in all. The top of the head and the back are almost black,-

but there is a narrow white line down the spine of the back, which I have not noticed in any

coloured wolf. Its sides are thinly covered with long, black, and some white hairs, and

there is a shorter dense coat of yellowish-gray wool, like that of the wolf, which is partly

visible. The tail, like the back, is clothed with black and white hairs, the latter predominating

at its tip. There is a thick wool on the tail concealed by the longer hairs.

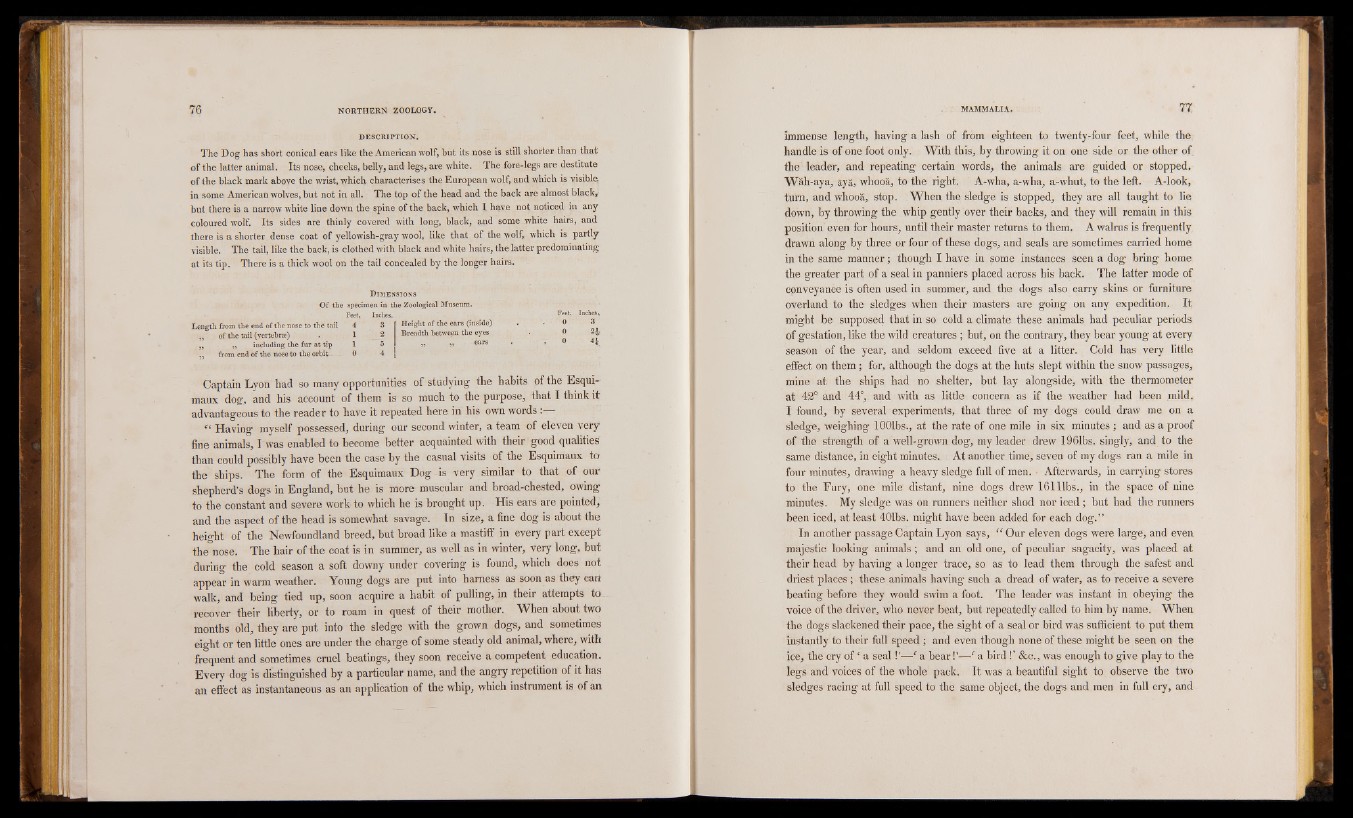

Dimensions

Of the specimen in the Zoological Museum.

Feet, Inches.

le n g th from the end of the nose to the tail 4 3 I Height of the ears (inside)

of the tail (yertebrse) . 1 2 Breadth between the eyes

Feet, Inches, 0 3

0 24

0 4^

5J „ including the fur at tip 1 5 { s> » ears

,, •’ from end of the nose to the orbit 0 4 |

Captain Lyon had so many opportunities of studying the habits of the Esquimaux

dog, and his account of them is so much to the purpose, that I think it

advantageous to the reader to have it repeated here in his own words :—

ec Having myself possessed, during our second winter, a team of eleven very

fine animals, I was enabled to become better acquainted with their good qualities

than could possibly have been the case by the casual visits of the Esquimaux to

the ships. The form of the Esquimaux Dog is very similar to that of our

shepherd’s dogs in England, but he is more muscular and broad-chested, owing

to the constant and severe work to which he is brought up. His ears are pointed,

and the aspect of the head is somewhat savage. In size, a fine dog is about the

height of the Newfoundland breed, but broad like a mastiff in every part except

the nose. The hair of the coat is in summer, as well as in winter, very long, but

during the cold season a soft downy under covering is found, which does not

appear in warm weather. Young dogs are put into harness as soon as they cafl

walk, and being tied up, soon acquire a habit of pulling, in their attempts to

recover their liberty, or to roam in quest of their mother. When about two

months old, they are put into the sledge with the grown dogs, and sometimes

eight or ten little ones are under the charge of some steady old animal, where, with

frequent and sometimes cruel beatings, they soon receive a competent education.

Every dog is distinguished by a particular name, and the angry repetition of it has

an effect as instantaneous as an application of the whip, which instrument is of an

immense length, having a lash of from eighteen to twenty-four feet, while the

handle is of one foot only. With this, by throwing it on one side or the other of

the leader, and repeating certain words, the animals are guided or stopped.

Wah-aya, gya, whooa, to the right. A-wha, a-wha, a-whut, to the left. A-look,

turn, and whooa, stop. When the sledge is stopped, they are all taught to lie

down, by throwing the whip gently over their backs, and they will remain in this

position even for hours, until their master returns to them. A walrus is frequently

drawn along by three or four of these dogs, and seals are sometimes carried home

in the same manner; though I have in some instances seen a dog bring home

the greater part of a seal in panniers placed across his back. The latter mode of

conveyance is often used in summer, and the dogs also carry skins or furniture

overland to the sledges when their masters are going on any expedition. It

might be supposed that in so cold a climate these animals had peculiar periods

of gestation, like the wild creatures ; but, on the contrary, they bear young at every

season of the year, and seldom exceed five at a litter. Cold has very little

effect on them ; for, although the dogs at the huts slept within the snow passages,

mine at the ships had no shelter, but lay alongside, with the thermometer

at 42° and 44°, and with as little concern as if the weather had been mild.

I found, by several experiments, that three of my dogs could draw me on a

sledge, weighing lOOlbs., at the rate of one mile in six minutes; and as a proof

of the strength of a well-grown dog, my leader drew 1961bs. singly, and to the

same distance, in eight minutes. At another time, seven of my dogs ran a mile in

four minutes, drawing a heavy sledge full of men. Afterwards, in carrying stores

to the Fury, one mile distant, nine dogs drew 161 libs., in the space of nine

minutes. My sledge was on runners neither shod nor iced; but had the runners

been iced, at least 401bs. might have been added for each dog.”

In another passage Captain Lyon says, “ Our eleven dogs were large, and even

majestic looking animals; and an old one, of peculiar sagacity, was placed at

their head by having a longer trace, so as to lead them through the safest and

driest places; these animals having such a dread of water, as to receive a severe

beating before they would swim a foot. The leader was instant in obeying the

voice of the driver, who never beat, but repeatedly called to him by name. When

the dogs slackened their pace, the sight of a seal or bird was sufficient to put them

instantly to their full speed; and even though none of these might be seen on the

jce, the cry of ‘ a seal!’—‘ a bear!’—‘ a bird!’ &c., was enough to give play to the

legs and voices of the whole pack. It was a beautiful sight to observe the two

sledges racing at full speed to the same object, the dogs and men in full cry, and