the genus, but takes up its résidence in a different situation, generally under the

declivities of rocks, or at the foot of a bank, where the snow drifts over it to a great

depth ; a small hole, for the admission of fresh air, is constantly observed in the

dome of its den. This, however, has regard solely to the she-Bear, which

retires to her winter-quarters in November, where she lives without food, brings

forth two young about Christmas, and leaves the den in the month of March, when

the cubs are as large as a shepherd’s dog. If perchance her offspring are tired,

they ascend the back of the dam, where they ride secure either in water or ashore.

Though they sometimes go nearly thirty miles from the sea in winter, they always

come down to the shores in the spring with their cubs, where they subsist on seals

and sea-weed. The he-Bear wanders about the marshes and adjacent parts

until November, and then goes out to the sea upon the ice, and preys upon seals.

They are very fat, and though very inoffensive if not meddled with, they are very

fierce when provoked*.’’

Captain Lyons records the Esquimaux account of the hibernation of the Polar

Bear in the following words : “ From Ooyarrakhioo, a most intelligent man, I obtained

an account of the Bear, which is too interesting to be passed over in silence.

At the commencement of winter, the pregnant Bears are very fat, and always

solitary. When a heavy fall of snow sets in, the animal seeks some hollow place

in which she can lie down, and remains quiet, while the snow covers her. Sometimes

she will wait until a quantity of snow has fallen, and then digs herself a

cave: at all events, it seems necessary that she should be covered by and lie

amongst the snow. She now goes to sleep, and does not wake until the spring

sun is pretty high, when she brings forth two cubs. The cave, by this time, has

become much larger, by the effect of the animal’s warmth and breath, so that the

cubs have room enough to move, and they acquire considerable strength by continually

sucking. The dam at length becomes so thin and weak, that it is with

great difficulty she extricates herself, when the sun is powerful enough to throw

a strong glare through the snow which roofs the den.’ The Esquimaux affirm that

during this long confinement the Bear has no evacuations, and is herself the means

of preventing them by stopping all the natural passages with moss, grass, or

earth. The natives find and kill the Bears during their confinement by means of

dogs, which scent them through the snow, and begin scratching and howling very

eagerly. As it would be unsafe to make a large opening, a long trench is cut of

sufficient width to enable a man to look down, and see where the Bear’s head lies,

* Graham, MSS. p. 20.

and he then selects a mortal part into which he thrusts his spear. The old one

being killed, the hole is broken open, and the young cubs may be taken out by

the hand, as, having tasted no blood and never having been at liberty, they are

then very harmless and quiet. Females which are not pregnant roam throughout

the whole winter in the same manner as the males. The coupling time is May.”

The flesh of the Polar Bear is, as stated by Captain Phipps (Lord Mulgrave),

exceedingly coarse. The Russian sailors who wintered in Spitzbergen, found it,

on the other hand, much more agreeable to the taste than the flesh of the reindeer.

I quote this fact here, not to show that there was any thing peculiarly

gross in the taste of the Russians, but to have an opportunity of remarking, that

when people have fed for a long time solely upon lean animal food, the desire for

fat meat becomes so insatiable, that they can consume a large quantity of unmixed,

and even oily fat, without nausea. Our seamen relish the paws of the

Bear, and the Esquimaux prefer its flesh at all times to that of the seal. Instances

are recorded of the liver of the Polar Bear having poisoned people.

The reader who is desirous of fuller accounts of the manners and habits of this

very curious animal will be gratified by turning to Marten’s Spitzbergen, Fabricius’

Fauna Groenlandica, Pennant’s Arctic Zoology, and Scoresby’s Account of the

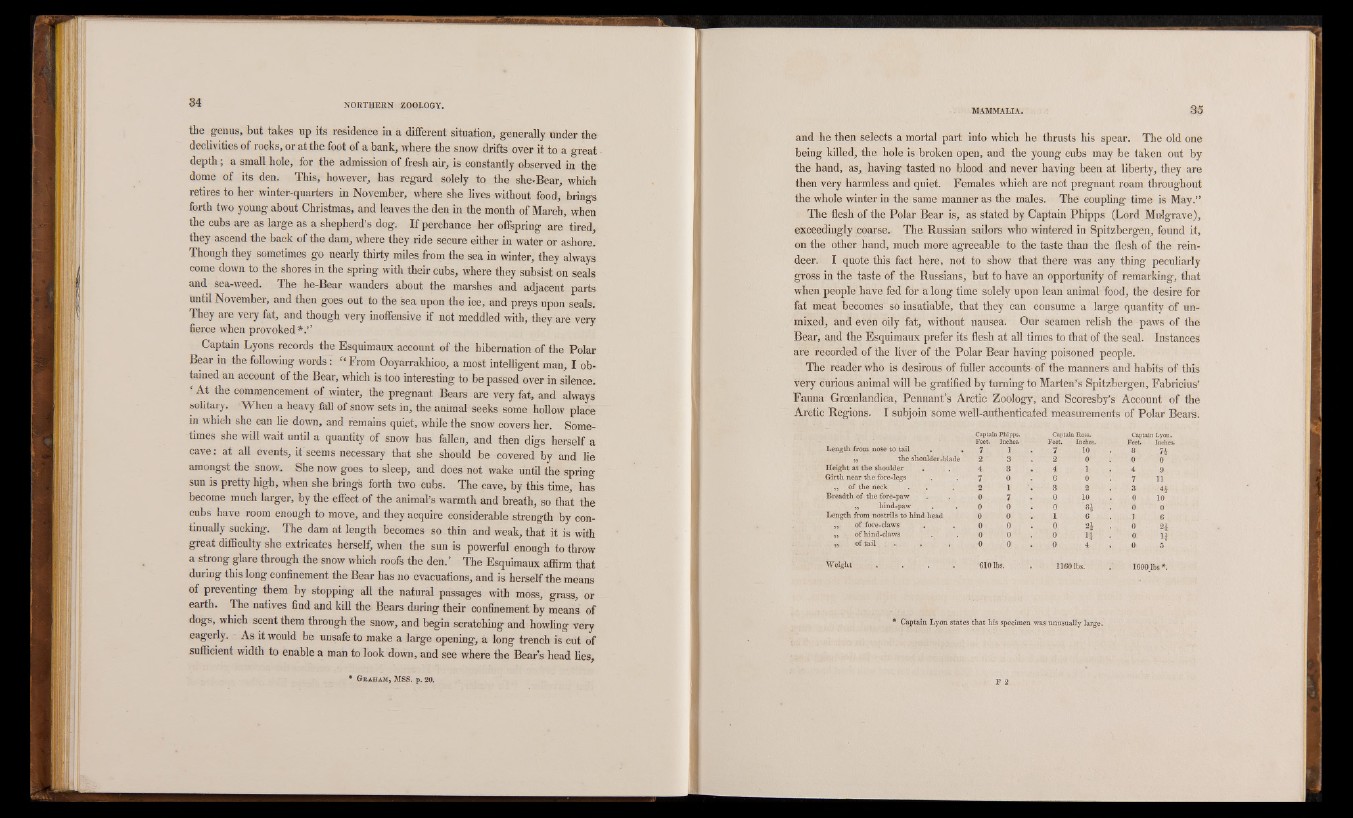

Arctic Regions. I subjoin some well-authenticated measurements of Polar Bears.

Length from nose to tail . ,

Captain Phipps. Captain Ross.

Feet. Inches. Feet. Inches.

7 1 - 7 10

Captain Lyon.

Feet. Inches.

8 74

„ the shoulder-blade 2 3 . 2 0 0 0

Height at the shoulder . 4 3 . 4 1 4 9

Girth near the fore-legs 7 0 . 6 0 7 11

. „ of the neck 2 1 . 3 2 3 44

Breadth of the fore-paw 0 7 . 0 10 0 10

,, hind-paw 0 0 . 0 81 . 0 0

Length from nostrils to hind head 0 0 . 1 6 ] 6

,, of fore-daws . 0 0 . 0 2è • 0 24

,, of hind-daws 0 0 . 0 I f 0 14

„ of tail . . 0 0 . 0 4 0

Weight . . . 610 lbs. . 1160 lbs. leoo.ibs *.

* Captain Lyon states that his specimen was unusually large.