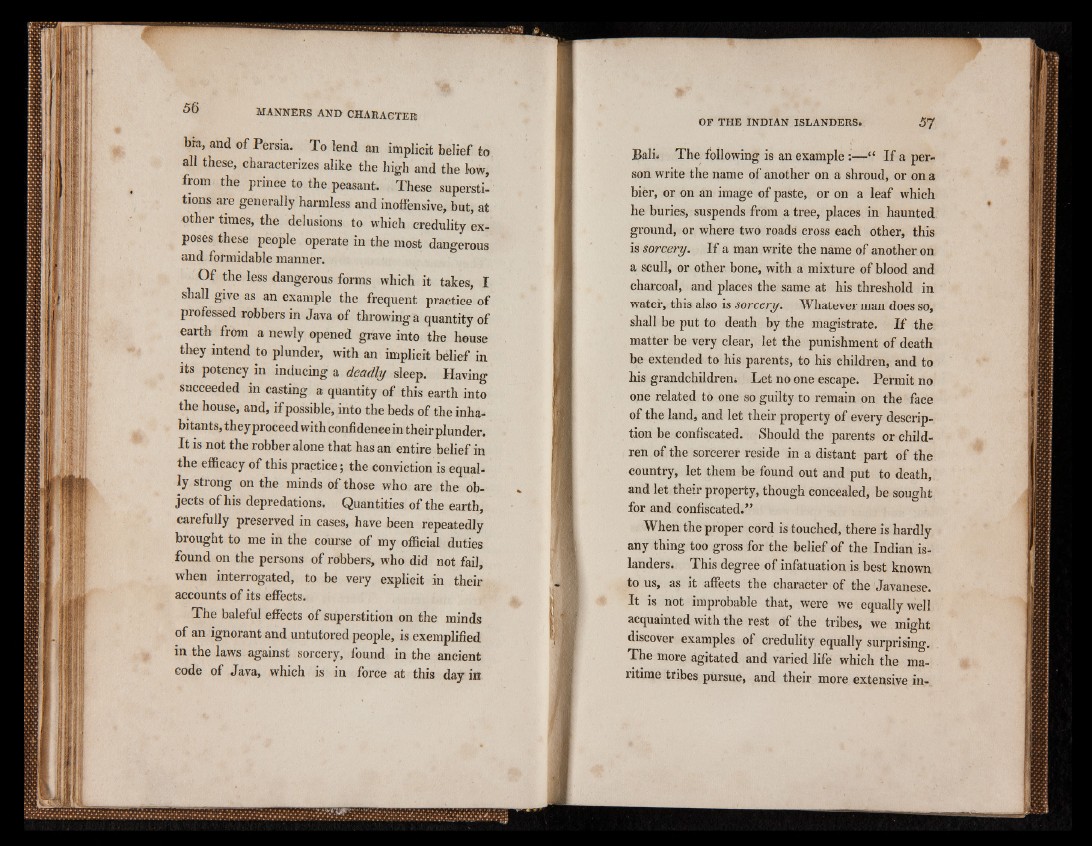

56 m a n n e r s a n d ch a racter

bra, and of Persia. To lend an implicit belief to

all these, characterizes alike the high and the low,

from the prince to the peasant. These superstitions

are generally harmless and inoffensive, but, at

other times, the delusions to which credulity exposes

these people operate in the most dangerous

and formidable manner.

Of the less dangerous forms which it takes, I

shall give as an example the frequent practice of

professed robbers in Java of throwing a quantity of

earth from a newly opened grave into the house

they intend to plunder, with an implicit belief in

its potency in inducing a deadly sleep. Having

succeeded in casting a quantity of this earth into

the house, and, if possible, into the beds of the inhabitants,

they proceed with confidence in their plunder.

It is not the robber alone that has an entire belief in

the efficacy of this practice; the conviction is equally

strong on the minds of those who are the objects

of his depredations. Quantities of the earth,

carefully preserved in cases, have been repeatedly

brought to me in the course of my official duties

found on the persons of robbers, who did not fail,

when interrogated, to be very explicit in their

accounts of its effects.

The baleful effects of superstition on the minds

of an ignorant and untutored people, is exemplified

in the laws against sorcery, found in the ancient

code of Java, which is in force at this day in

Bali< The following is an example :—“ If a person

write the name of another on a shroud, or on a

biér, or on an image of paste, or on a leaf which

he buries, suspends from a tree, places in haunted

ground, or where two roads cross each other, this

is sorcery. If a man write the name of another on

a scull, or other bone, with a mixture of blood and

charcoal, and places the same at his threshold in

water, this also is sorcery. Whatever man does so,

shall be put to death by the magistrate. I f the

matter be very clear, let the punishment of death

be extended to his parents, to his children, and to

his grandchildren* Let no one escape. Permit no

one related to one so guilty to remain on the face

of the land, and let their property of every description

be confiscated. Should the parents or children

of the sorcerer reside in a distant part of the

country, let them be found out and put to death,

and let their property, though concealed, be sought

for and confiscated.”

When the proper cord is touched, there is hardly

any thing too gross for the belief of the Indian islanders.

This degree of infatuation is best known

to us, as it affects the character of the Javanese.

It is not improbable that, were we equally well

acquainted with the rest of the tribes, we might

discover examples of credulity equally surprising.

The more agitated and varied life which the maritime

tribes pursue, and their more extensive in