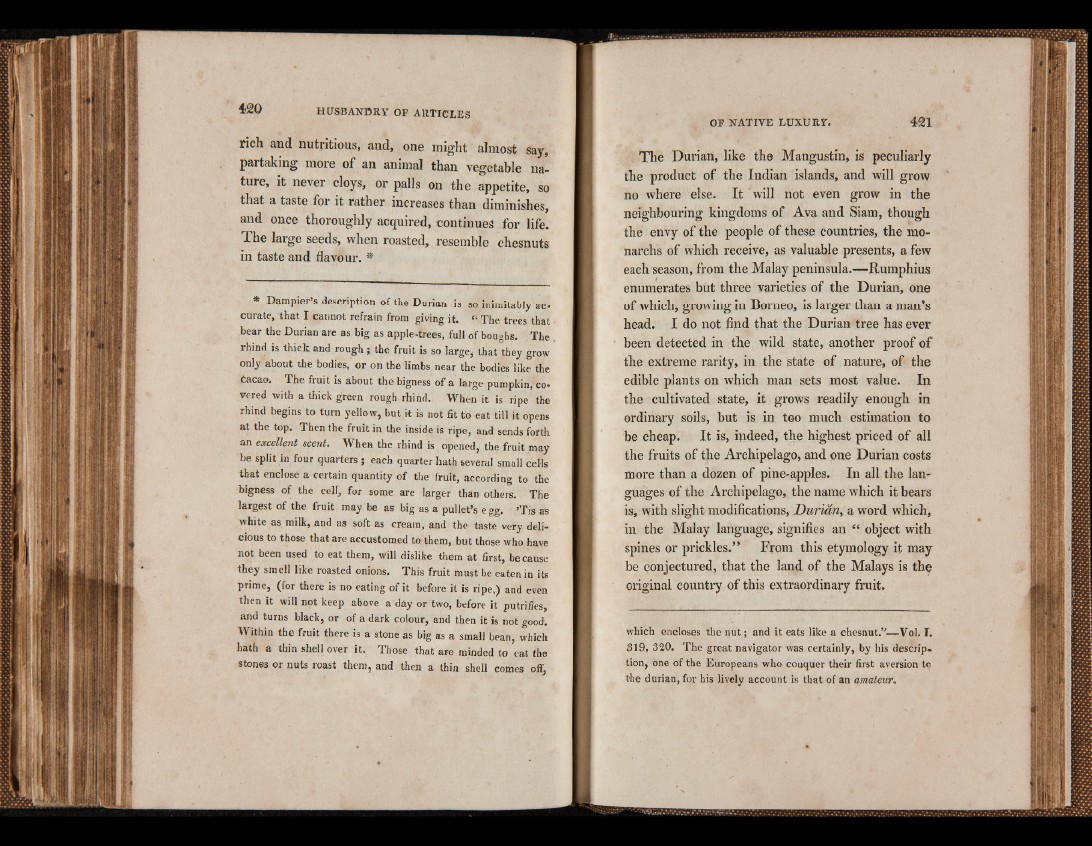

rich and nutritious, and, one might almost say,

partaking more of an animal than vegetable nature,

it never cloys, or palls on the appetite, so

that a taste for it father increases than diminishes,

and once thoroughly acquired, -continues for life.

The large seeds, when roasted, resemble chesnuts

in taste and flavour. *

* Dampier’s description of the Durian is so inimitably ac-

curate, that I cannot refrain from giving it. “ The trees that

bear the Durian are as big as apple-trees, full of boughs. The

rhind is thick and rough ; the fruit is so large* that they grow

only about the bodies, or on the limbs near the bodies like the

Cacao. The fruit is about the bigness of a large-pumpkin, covered

with a thick green rough rhind. When it is ripe the

rhind begins to turn yellow, but k is not fit to eat till it opens

at the top. Then the fruit in the inside is ripe, and sends forth

an excellent scent. When the rhind is opened, the fruit may

be split in four quarters ; each quarter hath several small cells

that enclose a certain quantity of the fruit, according to the

bigness of the cel 1, for some are larger than others. The

largest of the fruit may be as big as a pullet’s egg. ’Tis as

white as milk, and as soft as cream, and the taste very delicious

to those that are accustomed to them, but those who have

not been used to eat them, will dislike them at first, because

they smell like roasted onions. This fruit must be eaten in its

prime, (for there is no eating of it before it is ripe,) and even

then it will not keep above a day or two, before it putrifies,

and turns black, or of a dark colour, and then it is not good.

Within the fruit there is a stone as big as a small bean, which

hath a thin shell over it. Those that are minded to eat the

stones or nuts roast them, and then a thin shell conies off,

The Durian, like the Mangustin, is peculiarly

the product of the Indian islands, and will grow

no where else. It will not even grow in the

neighbouring kingdoms of Ava and Siam, though

the envy of the people of these countries, the monarch's

of which receive, as valuable presents, a few

each season, from the Malay peninsula.—Rumphius

enumerates but three varieties of the Durian, one

of which, growing in Borneo, is larger than a man’s

head. I do not find that the Durian tree has ever

been detected in the wild state, another proof of

the extreme rarity, in the state of nature, of the

edible plants on which man sets most value. In

the cultivated state, it grows readily enough in

ordinary soils, but is in too much estimation to

be cheap. It is, indeed, the highest priced of all

the fruits of the Archipelago, and one Durian costs

more than a dozen of pine-apples. In all the Ian-'

guages of the Archipelago, the name which it bears

is, with slight modifications, Durian, a word which,

in the Malay language, signifies an “ object with

spines or prickles.” From this etymology it may

be conjectured, that the land of the Malays is the

original country of this extraordinary fruit.

which encloses the nut ; and it eats like a chesnut.’'—.Vol. I.

319, 320. The great navigator was certainly, by his description,

one of the Europeans who conquer their first aversion to

the durian, for his lively account is that of an amateur.