and, instead of wearing the leather apron and tail of

the Latookas, they are contented with à slight fringe

of leather shreds, about four inches long by two broad,

suspended from a belt. The unmarried girls are

entirely naked ; or, if they are sufficiently rich in

finery,,they wear three or four strings of small white

beads, about three inches in length, as a covering.

The old ladies are antiquated Eves, whose dress consists

of a string round the waist, in which is stuck a

bunch of green leaves, the stalks uppermost. I have

seen a few of the young girls that were prudes, indulge

in such garments; but they did not appear to be

fashionable, and were adopted faute de mieux, One

great advantage was possessed by this costume,—it

‘ was always clean and. fresh,, and. the nearest bush (if

not thorny) provided a clean petticoat. When in the

society of these very simple and in demeanour always

modest Eves, I could not help reflecting upon the

Mosaical description of our first parents, "an d .th ey

sewed fiog -leaves togoether."

Some of the Obbo women were very pretty. The

caste of feature was entirely different to that of the

Latookas, and a striking peculiarity was displayed in

the. finely-arched noses of. many, of the natives, which

Strongly reminded one. of the Somauli tribes, ' It

wasyimpossible to . conjecture their origin, as they

had neither traditions nor ideas of their past

history.

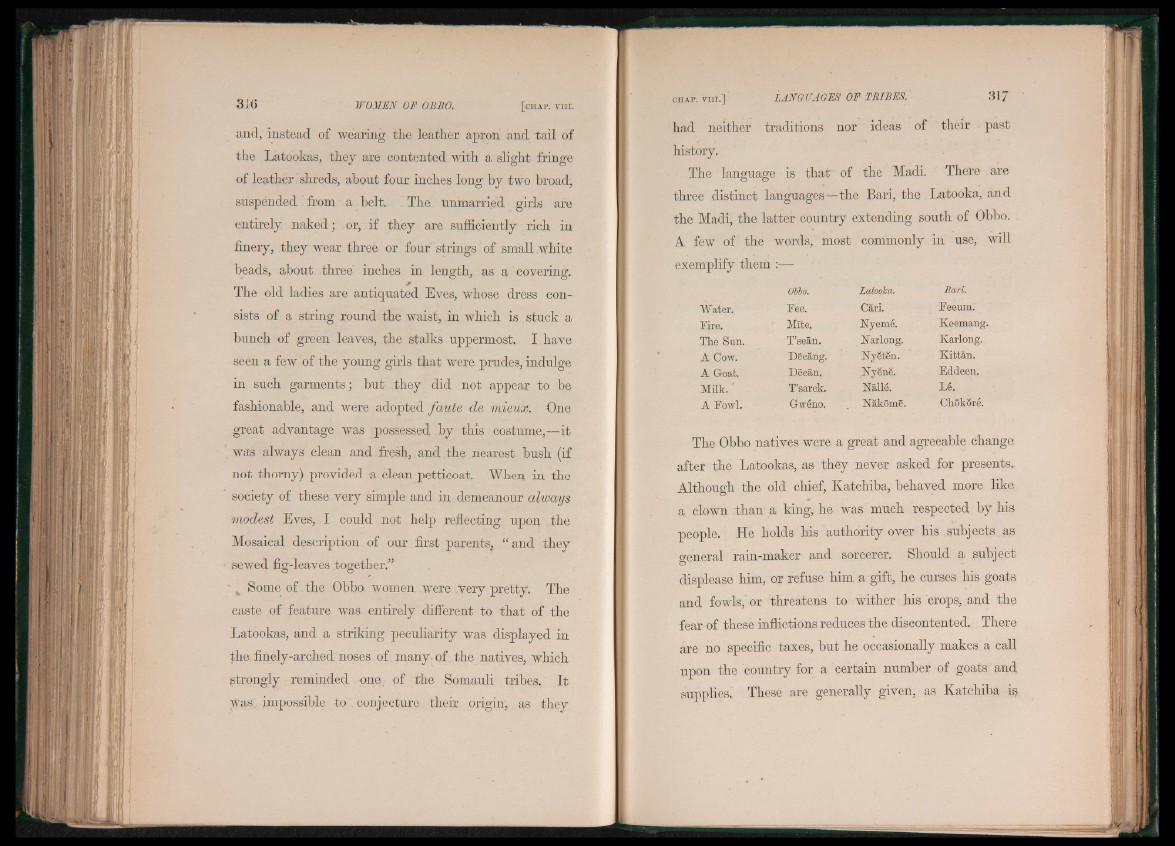

The lango uagoe is that of the Madi. There are

three distinct languages—the Bari, the Latooka, and

the Madi, the latter country extending south of Obbo.

A few of the words,’ most commonly in use, will

exemplify them

Obbo. Latooka. Bari.

Water. Fee. Câri. Feeum.

Fire. Mite, Nyemé. Keemang.

Tlie Sun. T’seân. FTarlong. Karlong.

A Cow. Dëeâng. Nÿëtën. Kittàn.

A Goat.' Dëeân, Nyënë. Eddeen,

Milk.' T’sarck. îtâllé. Lé.

A Fowl. Gwéno. Nakômë. Chôkëré.

The Obbo natives were a great and agreeable change

after the Latookas, as they never asked for presents.

Although the old chief, Katchiba, behaved more like

a clown than a king, he was much respected by his

people. He holds his authority over his subjects as

general rain-maker and sorcerer. Should a subject

displease him, or refuse him a gift, he curses his goats

and fowls,' or threatens to wither his crops, and the

fear of these inflictions reduces the discontented. There

are no specific taxes, but he occasionally makes a call

upon the country for a certain number of goats and

supplies.” These are generally given, as Katchiba is