I

140 CEANIA BUITANNICA. [CHAP. V.

cliaractcrs was doubtless deriyed from the MassaUot Greeks *, but after the Eomau conquest of

GaiJ it gradually gave way to that of Latin letters. On various Gaulish coins are Celtic names

in Greek letters, whilst on others of a later date the Eoman forms are found. Two lapidary

inscriptions in the Celtic tongue, one from the country of the Vocontii, the other from Msmes,

are in Greek chai-aeters t ; six others, from various parts of Celtic Gaul, are in Latin. The inscribed

Celtic coins of Britain, aU perhaps later than the Eoman conquest of Gaul, present

Eoman characters with a rare intermixture of Greek. No lapidary inscriptions of this period in

any Celtic dialect have been found in Britain i-

It is often maintained that the Britons and Irish possessed the ai-t of writing before they

derived it from the Greeks and Eomans; and then- supposed early alphabets are attributed to an

eastern source. There can be Uttle doubt that the Phoenicians of Gades communicated the use

of letters to the Turdetani §. In Britain, however, the Phoenicians had no permanent settlements,

as in the south of Spain; the Britons do not seem to have been prepared for such a gift;

and it was the mterest of these traders to keep them rude and uncivilized,—a policy not inconsistent

with the attempt to increase their own influence, by imparting some idea of their reKgion

and superstitions. The letters in the oldest MSS. || of the Irish and Welsh are of the corrupt

form of the Latin, in use in Europe in the fifth and several succeeding centm-ies, which are

known as Irish % or Anglo-Saxon. There caa be little doubt that -this alphabet was introduced

into Ireland by Patrick and other missionaries of the fifth and perhaps earlier centuries ; just as

we know that letters were given to the Goths by then- apostle Ulphilas, and to the Armenians

by Miesrob **. Latin letters were no doubt employed by the Britons during the Eoman occupation,

and were probably never entii-ely lost. The most ancient Welsh MSS., as weU as

sepulchral stones as early as of the sixth century, are in letters which do not much differ from

those of the Irish, or from those of the Anglo-Saxons after their conversion by Augustine.

Some Welsh writers claim for their cormtry the possession of what they call a Bardic

alphabettt of great antiquity. Unfortunately for these pretensions, which have been supported

by spm-ious Triads and other documents i t , no MSS. in such characters have been produced.

The very existence of such letters, unless as a late invention, appears negatived by the narrative

preserved in perhaps the oldest Welsh MS. in existence ; in which is an alphabet said to have

been invented by one Nemnivus, in consequence of the reproach of a certain Saxon that the

CHAP. V.] niSTOEICAL ETHNOLOGY OP BRITAIN. 141

* As may be inferred from Strabo, lib. IT. C. 1. § 5.

t Belloguet,p.l99. Pictet, "Inscript. Gauloises," pp. 11,17.

Stokes, "Irish Glosses," 1860, pp. 73, 100.

X No reliance can be placed on the yague report in Solinus

(c.22), "Ulyxem Caledonioe appnlsum manifestat ara Grsecis

Uteris scripta TOtum." Of the use of Greek characters by

Celtic nations further evidence has been found in Tacitus

(Germ. c. 3), who names monuments "Grtceis Uteris inscriptos"

on the borders of Germany and Ehsetia, the Jatter a Celtic

country. Both these vague notices are connected with the

story of the voyage of Ulysses to these parts. Ulysses seems

to represent supposed Greek expeditions, in the same way as

Hercules does those of the Phoenicians.

§ Strabo,lib.iii.c.I.§6. Kenrick,"Phoemcia,"p.l33. "We

know of no source but Phoenicia, whence i t " (this alphabet)

" could have been derived." This accords with the conclusions

of the Numismatists, De Saulcy and Longpérier (Akerman,

"Coins of Hispania," &c., p. 3—4). The graphic system of

the coins of Beetica is Semitic, reading from right to left with

the vowels suppressed ; the language is Iberian or Basque.

II The " Books of Kells and Dorrow," sometimes thought

of the sixth century, are perhaps the oldest of all; that of

Armagh is known to be of the early part of the ninth.

^ The Irish letters, particularly the capitals, are admitted

to have a character distinct from all others, which is traced to

the mutual influence of the Greek and Latin signs used by the

Irish Christian scribes. Reeves, "Li f e of St.Columba," p.xxii.

* * Neander, " Church History," vol. iii. pp. 160, 176, 178,

Eng. ed. 1851.

f t Coelbren y Beirrd (distinguished from the Coelbren y

Menaich, the Monkish or Roman alphabet), the subject of so

much speculation by Owen, Davies, Higgins, and others.

J t " lolo MSS. , " of Edward and Taliesin Williams (p. 617),

which are now believed to be inventions of the 17th century,

or perhaps even of a later date (Nash, Taliesin, &c., 1858,

pp. 35, 235).

Britons had no letters of their own*. These letters, thirty-three in number, have Welsh names,

and are similar in form to the Eunes of northern nations t : there is no proof of their having

been brought into use.

The claims of the Irish to an alphabet of untold antiquity, may at first sight seem to rest

on a surer foundation than those of the Welsh. The ordinary Irish letters are eighteen, viz.

a, h, G (pronounced hard like the Greek «.), d, e j , g, h, i, I, m, n, o, p, r, s, t, u. Of these, the

aspirate, h, is, by some, said to be a recent introduction, and to have been represented by a dot

above the line. Omitting Ji and/, a labial aspirate which answers to the Greek digamma, this

alphabet is identical with that of Cadmus of sixteen letters, a, /3, Y, S, e, I, K, X, v, o, IR, p, <7, T, U.

This correspondence has been insisted on as in favour of its Phoenician origin t Modern Irish

scholars are opposed to this view, and conclude that then- ancestors adopted " as many of the

Eoman letters as they required to express the simple sounds of the Irish language §." The

Welsh appear from the first to have employed a greater number of the Latin letters, as was

necessary for their phonetic mode of writing ||. It has, however, been maintained that the

Welsh alphabet is also Cadmean If, and that in its more ancient form it did not possess the w and y,

anymore than the j, k, q, x, and«, aU of which, according to some grammarians, are stiU unused.

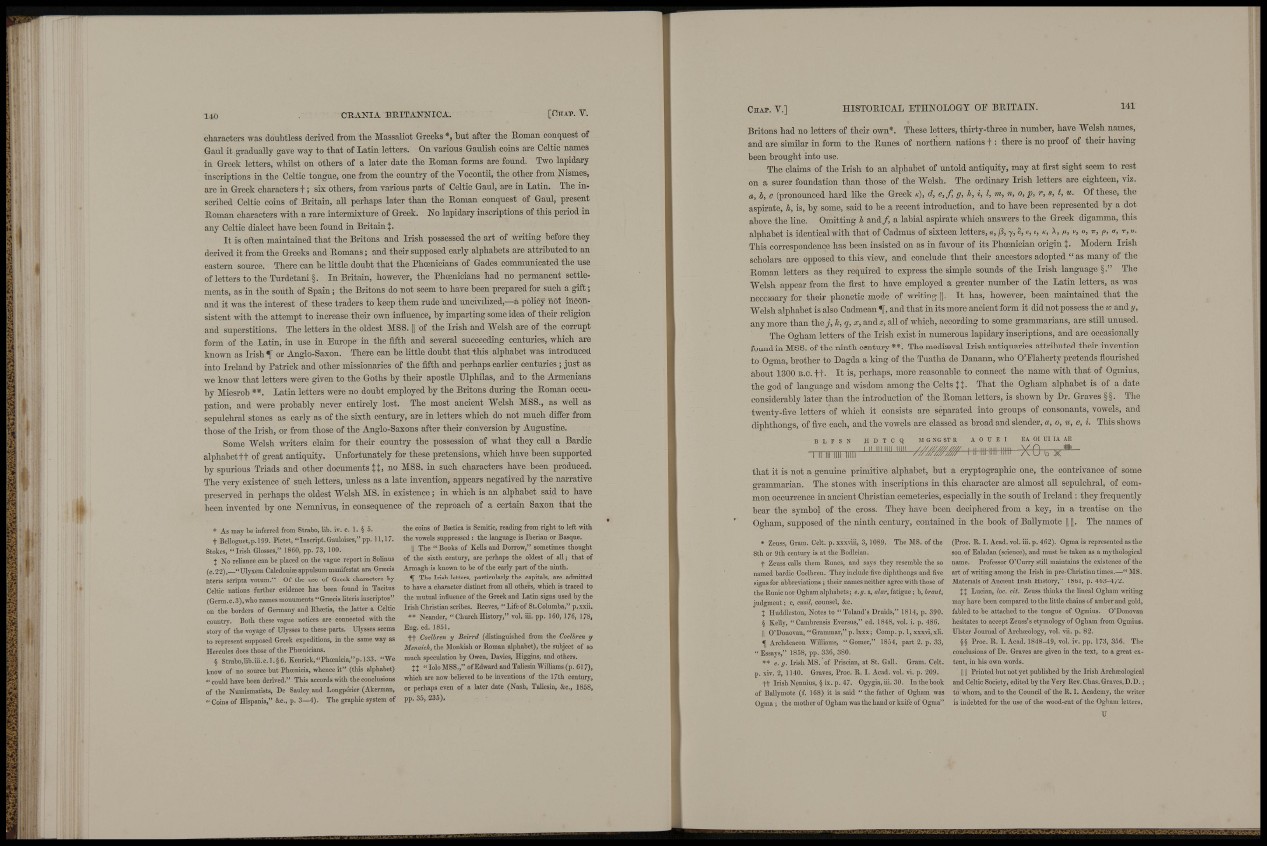

The Ogham letters of the Irish exist in numerous lapidary inscriptions, and are occasionally

found in MSS. of the ninth century **. The mediisval Irish antiquaries attributed their invention

to Ogma, brother to Dagda a king of the Tuatha de Danann, who O'Flaherty pretends flourished

about 1300 B.C. ft- It is, perhaps, more reasonable to connect the name with that of Ogmius,

the god of language and wisdom among the Celts tt- That the Ogham alphabet is of a date

considerably later than the introduction of the Eoman letters, is shown by Dr. Graves §§. The

twenty-five letters of which it consists are separated into groups of consonants, vowels, and

diphthongs, of five each, and the vowels are classed as broad and slender, a, o, u, e, i. This shows

B L F S N H D T 0 Q M G NG ST R A 0 U E I EA 01 UI LA AE

I mi l III "Nil nil inn mi ^ X O b X *

that it is not a genuine primitive alphabet, but a cryptographic one, the contrivance of some

grammarian. The stones ^ath inscriptions in this character are almost aU sepulchral, of common

occurrence in ancient Christian cemeteries, especially in the south of Ireland : they frequently

bear the symbol of the cross. They have been deciphered from a key, in a treatise on the

Ogham, supposed of the ninth centm-y, contained in the book of Ballymote ||||. The names of

• Zeuss, Gram. Celt. p. xxxviii, 3, 1089. The MS. of the

8th or 9th century is at the Bodleian.

f Zeuss calls them Runes, and says they resemble the so

named bardic Coelbren. They include five diphthongs and five

signs for abbreviations ; their names neither agree with those of

the Runic nor Ogham alphabets; e.ff.n, alar, fatigue ; h, brauf,

judgment; c, cimlt counsel, &c.

i Iluddleston, Notes to " Toland's Druids," 18N, p. 390.

§ Kelly, "Cambrensis Eversns," ed. 1848, vol. i. p. 486.

II O'Douovan, "Grammar," p. Ixxx; Comp. p. 1, xxxvi, xli.

^ Archdeacon Williams, " Gomer," 1854, part 2. p. 33,

"Essays," IB.iS, pp. 336, 380.

** e. y. Irish MS. of Priseian, at St. Gall. Gram. Celt,

p. xiv. 2, 1140. Graves, Proc. R. I. Acad. vol. vi. p. 209.

t t IrishNennius, § ix. p. 47. Ogygia, iii. 30. In the book

of Ballymote (f. 168) it is said " the father of Ogham was

Ogma ; the mother of Ogham was the hand or knife of Ogma"

(Proc. R. I . Acad. vol. iii. p. 462) . Ogma is represented as the

son of Ealadan (science), and must be taken as a mythologiciil

name. Professor O'Curry still maintains the existence of the

art of writing among the Irish in pre-Christian times.—" MS.

Materials of Ancient Irish History," 1S6I, p. 463-472.

I I Lueian, Joe. cit. Zeuss thinks the lineal Ogham writing

may have been compared to the little chains uf amber and gold,

fabled to be attached to the tongue of Ogmius. O'Donovan

hesitates to accept Zeuss's etymology of Ogham from Ogmius.

Ulster Journal of Archaeology, vol. vii. p. 82.

§§ Proc. R. I. Acad. 1848-49, vol. iv. pp. 173, 356. The

conclusions of Dr. Graves are given in the text, to a great extent,

in his own words.

IIII Printed but not yet published by the Irish Archffiological

and Celtic Society, edited by the Very Rev. Chas. Graves, D.D. ;

to whom, and to the Council of the R. 1. Academy, the writer

is indebted for the use of the wood-cut of the Ogham letters,

TJ