88 CRANIA BRITANNICA. [CHAP. IV. CHAP. IV. ] DISTORTIONS OP THE SKULL. 39

and, when wo come to witness its effects, they appear so extraordinary as to render the mind

almost iucrednlons in attributing them to any canse operating after death. Still, we have no

doubt, such is the fact. Our attention was fast directed to the subject by the reception, in

October 1848, of an imperfect distorted cranium from Mr. Bateman, foimd in an ancient British

Barrow at Alport in Derbyshire, and by the inspection of another example of an Anglo-Saxon

cranium from Stone in Buckinghamshire, in the collection of Dr. Thurnam. Of this latter

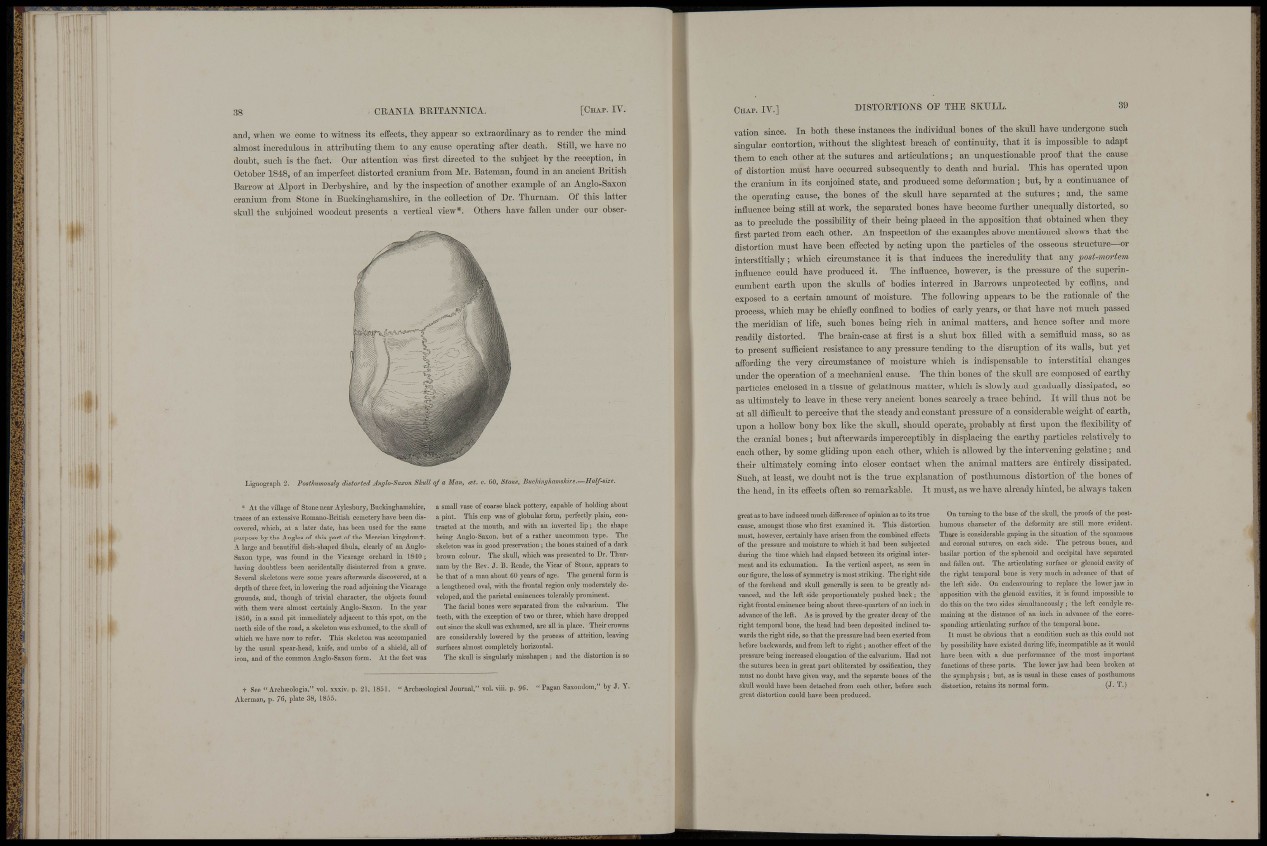

skull the subjoined woodcut presents a vertical view*. Others have fallen under our obser-

Lignograph 2. Posfh-umoushj distorted Anglo-Saxon Skull of a Urn, at. c. BO, Stone, BucIdni/hamsMre.—Half size.

* At tte village of Stone near Aylesbury, Buckinghamsliire,

traces of an extensive Romano-British cemetery have been discovered,

which, at a later date, has been nsed for the same

purpose by the Angles of this part of the Mercian kingdomf.

A large and beautiful dish-shaped fibula, clearly of an Anglo-

Saxon type, was found in the Vicarage orchard m 1840 ;

having doubtless been accidentally disinterred from a grave.

Several skeletons were some years afterwards discovered, at a

depth of three feet, iu lowering the road adjoining the Vicarage

grounds, and, though of trivial character, the objects found

with them were almost certainly Anglo-Saxon. In the year

1850, iu a sand pit immediately adjacent to this spot, on the

north side of the road, a skeleton was exhumed, to the skull of

which we have now to refer. This skeleton was accompanied

by the usual spear-head, knife, and umbo of a shield, all of

iron, and of the common Anglo-Saxon form. At the feet was

a small vase of coarse black pottery, capable of holding about

a pint. This cup was of globular form, perfectly plain, contracted

at the mouth, and with an inverted lip; the shape

bemg Anglo-Saxon, but of a rather uncommon type. The

skeleton was in good preservation ; the bones stained of a dark

brown colour. The skull, which was presented to Dr. Thurnam

by the Rev. J . 13. Eeade, the Vicar of Stone, appears to

be that of a man about 60 years of age. The general form is

a lengthened oval, with the frontal region only moderately developed,

and the parietal eminences tolerably prominent.

The facial bones were separated from the calvarium. Tiie

teeth, with the exception of two or three, which have dropped

out since the skull was exhumed, are all iu place. Their crowns

are considerably lowered by the process of attrition, leaving

surfaces almost completely horizontal.

The skull is singularly misshapen ; and the distortion is so

vation since. In both these instances the individual bones of the skull have undergone such

singular contortion, without the slightest breach of continuity, that it is impossible to adapt

them to each other at the sutures and articulations ; an unciuestionable proof that the cause

of distortion must have occurred subsequently to death and burial. This has operated upon

the cranium in its conjoined state, and produced some deformation ; but, by a continuance of

the operating cause, the bones of the skuU have separated at the sutures ; and, the same

influence being stUl at work, the separated bones have become further unequally distorted, so

as to preclude the possibility of their being placed in the apposition that obtained when they

first parted from each other. An inspection of the examples above mentioned shows that the

distortion must have been effected by acting upon the particles of the osseous structm-e—or

interstitiaUy ; which circumstance it is that induces the incredulity that any post-mortem

influence could have produced it. The influence, however, is the pressm-e of the superincumbent

earth upon the skuUs of bodies interred in Barrows unprotected by coflns, and

exposed to a certain amount of moisture. The following appears to be the rationale of the

process, which may be chiefly confined to bodies of early years, or that have not much passed

the meridian of Hfe, such bones being rich in animal matters, and hence softer and more

readily distorted. The brain-case at fast is a shut box flUed with a semifluid mass, so as

to present sufiicient resistance to any pressm-e tending to the disruption of its walls, but yet

affording the very circumstance of moisture which is indispensable to interstitial changes

under the operation of a mechanical cause. The thin bones of the skull are composed of earthy

particles enclosed in a tissue of gelatinous matter, which is slowly and gradually dissipated, so

as ultimately to leave in these very ancient bones scarcely a trace behind. It wiU thus not be

at an difficult to perceive that the steady and constant pressure of a considerable weight of earth,

upon a hoUow bony box like the skuU, should operate, probably at fa-st upon the flexibility of

the cranial bones ; but afterwards imperceptibly in displacing the earthy particles relatively to

each other, by some gUding upon each other, which is allowed by the intervening gelatine ; and

their ultimately coming into closer contact when the animal matters are entirely dissipated.

Such, at least, we doubt not is the true exxflanation of posthumous distortion of the bones of

the head, in its effects often so remarkable. It must, as we have already hinted, be always taken

t See " Archseologia," vol. xxxiv. p. 21, 1851.

Akerman, p. 76, plate 38, 1855.

"Archeeological Journal," vol. viii. p. 96. "Pagan Saxondom," by .1. Y.

great as to have induced much difference of opinion as to its true

cause, amongst those who first exammed it. This distortion

must, however, certainly have arisen fi-om the combined effects

of the pressure and moisture to which it had been subjected

during the time which had elapsed between its origmal interment

and its exhumation. In the vertical aspect, as seen in

our ligure, the loss of symmetry is most strikmg. The right side

of the forehead and skull generally is seen to be greatly advanced,

and the left side proportionately pushed back; the

right frontal eminence being about three-quarters of an inch in

advance of the left. As is proved by the greater decay of the

right temporal bone, the head had been deposited inclined towards

the right side, so that the pressure had been exerted from

before backwards, and from left to right; another effect of the

pressure being increased elongation of the calvarium. Had not

the sutures been in great part obhterated by ossification, they

must no doubt have given way, and the separate bones of the

skull would have been detached from each other, before such

great distortion could have been produced.

On turning to the base of the skull, the proofs of the posthumous

character of the deformity are still more evident.

There is considerable gaping in the situation of the squamous

and coronal sutures, on each side. The petrous bones, and

basilar portion of the sphenoid and occipital have separated

and fallen out. The articulating surface or glenoid cavity of

the right temporal bone is very much in advance of that of

the left side. On endeavourhig to replace the lower jaw in

apposition with the glenoid cavities, it is found impossible to

do this on the two sides simultaneously ; the left condyle remaining

at the distance of an inch in advance of the correspondiug

articulating surface of the temporal bone.

I t must be obvious that a condition such as this could not

by possibility have existed during life, incompatible as it would

have been with a due performance of the most important

functions of these parts. The lower jaw had been broken at

the symphysis ; but, as is usual in these cases of posthumons

distortion, retains its normal form. (J . T.)