ft y ''irl

II I

\¥

' ' t i l :

I

42 CRANIA BRITANNICA. [CiLVP. IV.

becomes a question, whetlier we may not regard this instance as an example of siich a custom.

Should this view bo once admitted, which 'ndll in all likelihood he ascertained by continued

observations in Germany, England and Prance, when the importance of attention to ancient

crania is properly appreciated, we may be in a position hereafter to question whether the

presumed skuUs of Avars, discovered ia so many different places of Austria and Switzerland, are

not reaUy relics of the aboriginal tribes who have died in their native seats. The facts are at

present scanty, but the writer has been of opinion, fi'om the first, that it is most probable

the result now indicated -ivill ultimately be found to he correct. Should such a conclusion

be established, this Harnham example wiU prove the practice to have been applied to females,

perhaps to have been brought from the forests of Germany by the Anglo-Saxon invaders

of Britain, and confirm the probability that it was not very generally, but on the contrary

rarely employed, as if it were a remnant of one of the ancient customs of the West Saxons

before they crossed the sea*.

But observations made in Prance bring to light the extraordinary fact that the practice of

distorting the skull in infancy is not yet extinct, even in Europe. The subject has engaged the

attention of an eminent observer, whose opportunities have been great—M. Eoville—who,

besides publishing a pamphlet relating to it some years agot, has again taken it up in his

large work on the Anatomy of the Nervous System. ' In the fine Atlas of this latter book.

Dr. Eovflle has figured examples of deformed heads of the rural population of Erance. One

singular instance, equalling in deviation from its natural state those of the ancient cemeteries of

Peru, is the head of a peasant of Normandy, who appears to have been an inmate of a lunatic

asylum. Dr. Poville informs us that distorting processes, which are concurrent with the

prevailing modes of applying constricting coverings to the heads of infants, obtain in different

provinces of Prance, with some variations in the proceedings adopted, and consequently in their

results. He gives pre-eminence to Normandy, hut mentions also Gascony, Limousin and

Brittany. Beam he expressly excepts as more favoured than other provinces, since the headdress

of infants is here attached by strings under the chin. It is also remarkable, as presenting

a sensibly less number of insane than other provinces in which the constrictive bandages are

used. This supports the author's opinion, that the distortion of the craniimi may have some

tendency to interfere with the functions of the brain, and in aU probability to induce insanity

and other diseases. Tet, in aUuding to one of the cities of those provinces in which the distortion

* This Harnham skull has a very close resemblance, both

in size and peculiarity of form, to that depicted in plate 3 of

the ' Crania Americana,' from a desiccated mummy of a Peruvian

woman, obtained on the borders of the desert of Ataeama.

To the description Dr. Morton adds, that the skulls

brought from Titicaca by Mr. Pentland " are strikingly like

the specimen here figured, both as respects their general form,

their narrow face, their small size and their several diameters;

yet they present more obvious marks of artificial modification "

(p. 108). The traces of the distorting jsrocess are exceedingly

slight, if at all perceptible, in the Saxon specimen. If, according

to the opinion of Dr. Tselindi, which we are aware receives

countenance from current hypotheses, we were to refer

this example to a Peruvian origin, we should commit a great

error. "Whether a reference to an Avarian source would be any

more correct, we have stated our doubts above.

There is an example of a posthumously distorted skull in

the British Museum, in an imperfect Anglo-Saxon cranium

derived from the cemetery of Little WUbraham m Cambridgeshire,

which was excavated by the Hon. R. C. Neville (Saxon

Obsequies, 1852). This instance has been somewhat lengthened,

and also obliquely flattened by the force compressing it

in the grave, which has dislocated the bones at the coronal

suture on one side, not on the other. It is by these two marks,

the imequal effects on the two sides, and the dislocations at

the sutures, that posthumous distortion may be best discriminated.

In the deformed cranium from Harnham they arc

both entirely wanting.

t Deformation du Crâne résultant de la Méthode la plus

générale de couvrir la Tête des Enfants, 1834.

CHAP. IV.] DISTORTIONS OP THE SKULL. 43

prevails and is very obvious, apparently Toulouse, the artists of which have not failed to mark

and represent the characteristic deformity of head in the portraits of the celebrated men of the

department hung up in the Hôtel de Ville, he admits that the deformation of the cranium is not

always an obstacle to the most perfect exercise of the inteUectual faciûties an opinion which is

more in accordance with that of Dr. Morton and others, who have had extensive opportunities of

observing the Indians of North America, who modify the form of the head so materially, and

yet exhibit no moral or inteUectual inferiority to such of their neighbours as are contented with

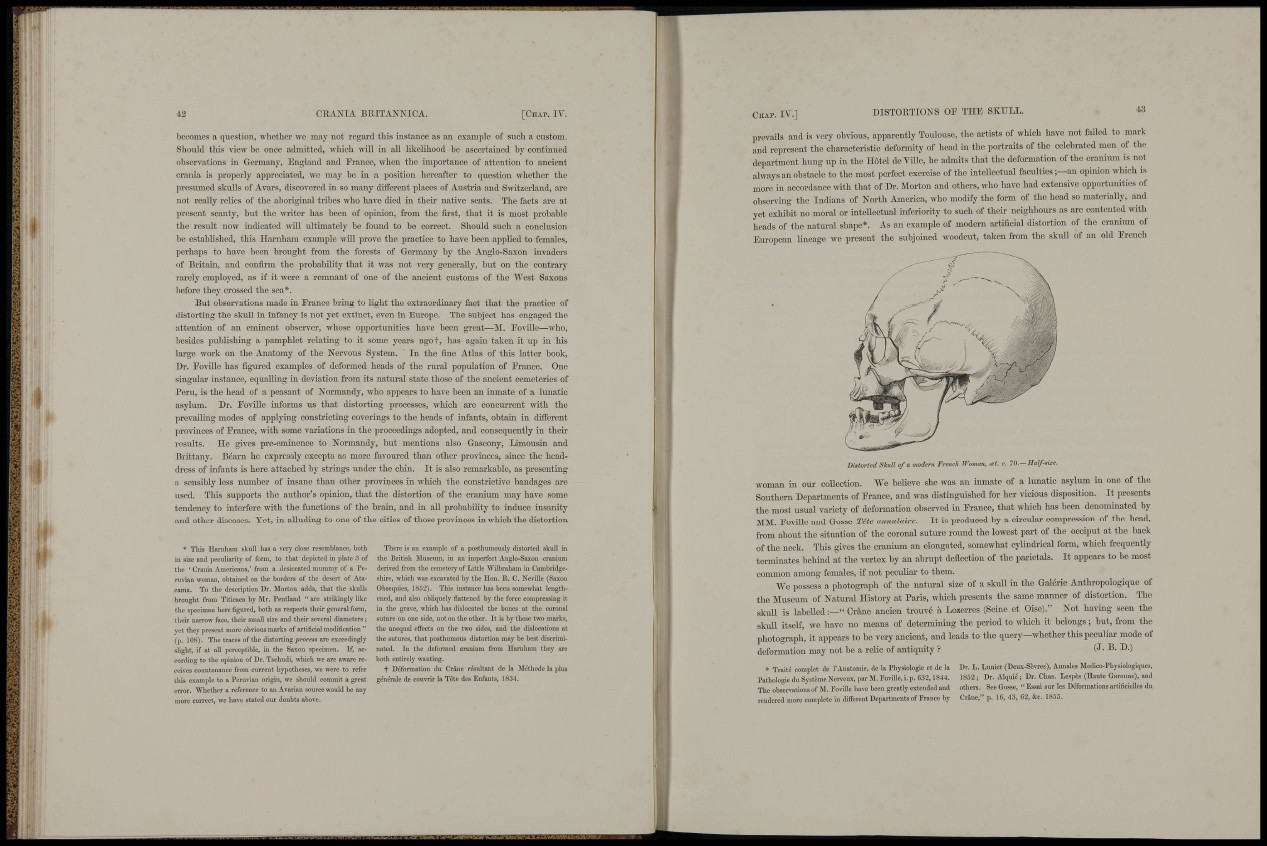

heads of the natural shape*. As an example of modern artificial distortion of the cranium of

Em-opean lineage we present the subjoined woodcut, taken from the skull of an old Prench

Distorted Skull of a modern French Woman, oet. c. 70.—Half-size.

woman in our coUection. We believe she was an inmate of a lunatic asylum in one of the

Southern Departments of Erance, and was distinguished for her vicious disposition. It presents

the most usual variety of deformation observed in Erance, that which has been denominated by

MM. Poville and Gosse Tête annulaire. It is produced by a circular compression of the head,

from about the situation of the coronal suture round the lowest part of the occiput at the hack

of the neck. This gives the cranium an elongated, somewhat cylindrical form, which frequently

terminates behind at the vertex by an abrupt deflection of the parietals. It appears to be most

common among females, if not peculiar to them.

We possess a photograph of the natiu-al size of a skull in the Galérie Anthropologique of

the Museum of Natural History at Paris, which presents the same manner of distortion. The

skull is laheUed " Crâne ancien trouvé à Lozerres (Seine et Oise)." Not having seen the

skuU itself, we have no means of determining the period to which it belongs ; but, from the

photograph, it appears to be very ancient, and leads to the query—whether this peculiar mode of

deformation may not he a relic of antiquity ?

* Traité complet de 1'Anatomic, de la Physiologie et de la

Pathologie du Système Nerveux, par M. Foville, i. p. 632,1844.

The observations of M. Foville have been greatly extended and

rendered more complete in different Departments of France by

( J . B. D.)

Dr. L. Lunier (Deux-Sèvres), Annales Medieo-Physiologiques,

1852; Dr. Alquié; Dr. Chas. Lespès (Haute Garonne), and

others. See Gosse, " Essai sur les Déformations artificielles du

Crâne," p. 16, 43, 62, &c. 1855.

r i •