40 CRANIA BRITANNICA. [CHAP. IV.

into account in the subject now treated of, and may probably present itself as a complicating and

aggravating influence in distorted crania, whether they have been primarily deformed by art or

disease—another mode of deformation which produces singular- changes, hitherto not suificiently

studied.

In the excavations made in the Anglo-Saxon cemetery at Harnham in AViltshire in 1853,

under the careful and judicious supervision of the Secretary to the Society of Antiquaries, Mr. J.

Y. iU^erman, an example of a distorted cranium was brought to light of much interest. We are

indebted to the kind desire of that gentleman to promote the present inquiry for this and other

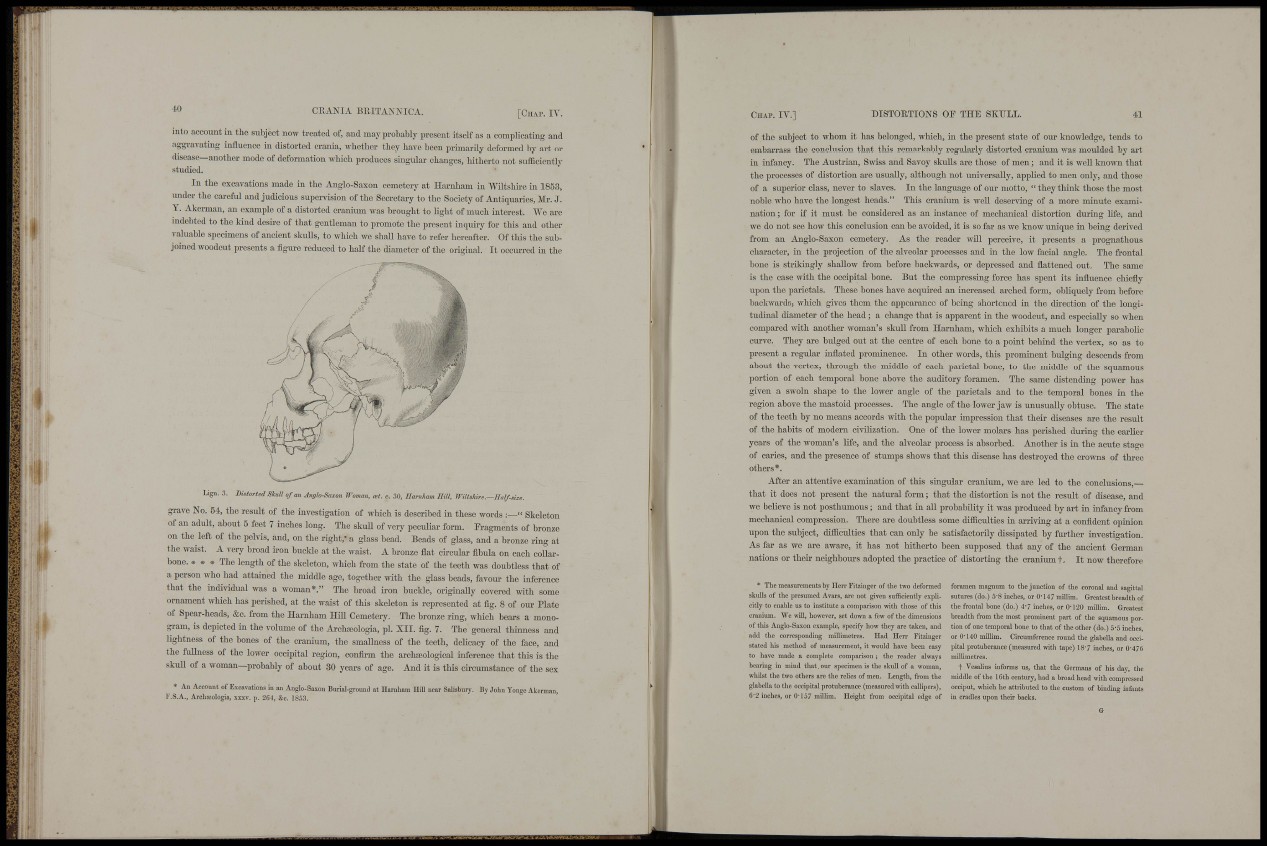

valuable specimens of ancient skuUs, to which we shaU have to refer hereafter. Of this the subjoined

woodcut presents a flgui'e reduced to half the diameter of the original. It occiu-red in the

Lign. 3. Distorted Skull of an Anglo-Saxon Woman, at. c. 30, Harnham Rill, Wiltshire.—Half-size.

grave No. 54, the result of the investigation of which is described in these words " Skeleton

of an adult, about 5 feet 7 inches long. The skuU of very peculiar form. Fragments of bronze

on the left of the pelvis, and, on the right," a glass bead. Beads of glass, and a bronze ring at

the waist. A very broad ii-on buckle at the waist. A bronze flat circular fibula on each collarbone.

* * * The length of the skeleton, which from the state of the teeth was doubtless that of

a person who had attained the midcUe age, together with the glass beads, favom- the inference

that the individual was a woman*." The broad iron buckle, originally covered with some

ornament which has perished, at the waist of this skeleton is represented at fig. 8 of our Plate

of Spear-heads, &c. from the Harnliam Hill Cemetery. The brom;e ring, which bears a monogram,

is depicted in the volume of the Archajologia, pi. XII. fig. 7. The general thinness and

lightness of the bones of the cranium, the smaUness of the teeth, deHcacy of the face, and

the fullness of the lower occipital region, confirm the archisological inference that this is the

skull of a woman—probably of aboiit 30 years of age. And it is this circumstance of the sex

* An Account of Excavations in an Anglo-Saxon Burial-ground at Harnham Hill near Salisbury. By John Yonge Akerman,

F.S.A., Archseologia, xictv. p. 264, &c. 18.53.

CLIAP. IV. ] DISTORTIONS OE THE SKULL. 41

of the subject to whom it has belonged, which, in the present state of our knowledge, tends to

embarrass the conclusion that this remarkably regularly distorted cranium was moulded by art

in infiincy. The Austrian, Swiss and Savoy skulls are those of men ; and it is weU known that

the processes of distortion are usually, although not universally, appUed to men only, and those

of a superior class, never to slaves. In the language of our motto, " they think those the most

noble who have the longest heads." This cranium is weU deserving of a more minute examination

; for if it must be considered as an instance of mechanical distortion during hfe, and

we do not see how this conclusion can be avoided, it is so far as we know unique in being derived

from an Anglo-Saxon cemetery. As the reader will perceive, it presents a prognathous

character, in the projection of the alveolar processes and in the low facial angle. The frontal

bone is strikingly shallow from before backwards, or depressed and flattened out. The same

is the case with the occipital bone. But the compressing force has spent its influence chiefly

upon the parietals. These bones have acquired an increased arched form, obliquely from before

backwards, which gives them the appearance of being shortened in the direction of the longitudinal

diameter of the head ; a change that is apparent in the woodcut, and especially so when

compared with another woman's skull from Harnham, which exhibits a much longer parabolic

curve. They are bulged out at the centre of each bone to a point behind the vertex, so as to

present a regular inflated prominence. In other words, this prominent bulging descends from

about the vertex, through the middle of each parietal bone, to the middle of the squamous

portion of each temporal bone above the auditory foramen. The same distending power has

given a swoln shape to the lower angle of the parietals and to the temporal bones ia the

region above the mastoid processes. The angle of the lower jaw is unusually obtuse. The state

of the teeth by no means accords with the popular impression that their diseases are the result

of the habits of modern civilization. One of the lower molars has perished during the earlier

years of the woman's life, and the alveolar process is absorbed. Another is in the acute stage

of caries, and the presence of stumps shows that this disease has destroyed the crowns of three

others*.

After an attentive examination of this singular cranium, we are led to the conclusions,—

that it does not present the natm-al form ; that the distortion is not the result of disease, and

we beHeve is not posthumous ; and that in aU probability it was produced by art in infancy from

mechanical compression. There are doubtless some difficulties in arriving at a confident opinion

upon the subject, difficulties that can only be satisfactorily dissipated by further investigation.

As far as we are aware, it has not hitherto been supposed that any of the ancient German

nations or their neighbours adopted the practice of distorting the cranium f . It now therefore

* The measurements by Herr Fitzinger of the two deformed

skulls of the presumed Avars, are not given sufficiently explicitly

to enable us to institute a comparison with those of this

cranium. "We will, however, set down a few of the dimensions

of this Anglo-Saxon example, specify how they are taken, and

add the corresponding millimetres. Had Herr Fitzinger

stated his method of measurement, it would have been easy

to have made a complete comparison; the reader always

bearing in mind that.our specimen is the skull of a woman,

whilst the two others are the rehes of men. Length, from the

glabella to the occipital protuberance (measured with callipers),

(i-2 inches, or 0-157 millim. Height from occipital edge of

foramen magnum to the junction of the coronal and sagittal

sutures (do.) 5'8 inches, or 0'147 millim. Greatest breadth of

the frontal bone (do.) 4 7 inches, or 0-120 millim. Greatest

breadth from the most prominent part of the squamous portion

of one temporal bone to that of the other (do.) S S inches,

or 0-140 millim. Circumference round the glabella and occipital

protuberance (measured with tape) 187 mches, or 0-476

millimetres.

t Vesalius informs us, that the Germans of his day, the

middle of the 16th century, had a broad head with compressed

occiput, which he attributed to the custom of binding infants

in cradles upon their backs.

G