quick to perceive the motion, and, digging with rapidity, grips the soft velvety

coat and drags out the impotent prey.

‘ It may be questioned whether field-mice are often caught by the Marten.

Shrews are not found very far from cultivation, and other kinds of mice are scarce

on the bare highlands. But all the members of the weasel family subsist upon

mice when they can catch them and when other food is not obtainable. An

animal so wary as the Marten is rarely surprised, even in such a wilderness as

that described. Its scent, sight, and hearing are exceedingly acute. Long hours,

and often whole days, of watching must be spent by one who wishes to see the

creature, whether at work or play. It is, indeed, easier to trap a Marten than to

observe one at liberty. Foxes, and especially fox cubs, may be seen on a moonlight

night by any enthusiastic field naturalist who possesses the patience to remain

perched for an hour or so in a tree near an “ earth.” The otter will sometimes

show itself to the salmon fisher in a summer twilight, or before the sun is up;

but an opportunity seldom occurs for watching the Marten on the track of a hare

or sneaking up to a sitting grouse. It is not surprising that the oldest native of

a locality wherein Martens are still to be found shakes his head at the assertions

of a naturalist who has been at pains to make the discovery.

‘ In the stillness of a winter’s morn slight sounds are borne from afar. The

scream of a rabbit is heard, and, coming nearer, the cry of the hunted animal is

repeated. A streak of grey, the glimpse of a white scut, and a terrified coney

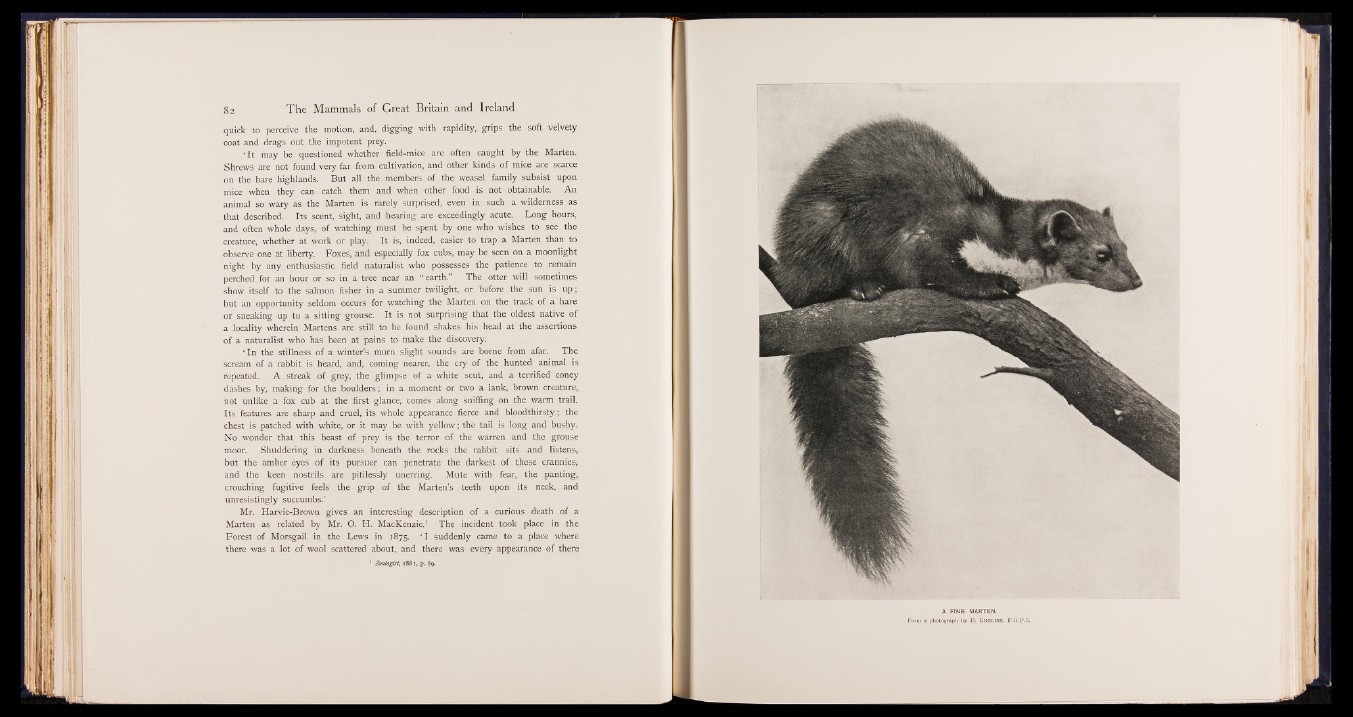

dashes by, making for the boulders; in a moment or two a lank, brown creature,

not unlike a fox cub at the first glance, comes along sniffing on the warm trail.

Its features are sharp and cruel, its whole appearance fierce and bloodthirsty; the

chest is patched with white, or it may be with yellow; the tail is long and bushy.

No wonder that this beast of prey is the terror of the warren and the grouse

moor. Shuddering in darkness beneath the rocks the rabbit sits and listens,

but the amber eyes of its pursuer can penetrate the darkest of these crannies,

and the keen nostrils are pitilessly unerring. Mute with fear, the panting,

crouching fugitive feels the grip of the Marten’s teeth upon its neck, and

unresistingly succumbs.’

Mr. Harvie-Brown gives an interesting description of a curious death of a

Marten as related by Mr. O. H. MacKenzie.1 The incident took place in the

Forest of Morsgail in the Lews in 1875. ‘ I suddenly came to a place where

there was a lot of wool scattered about, and there was every appearance of there