13 0 The Mammals of Great Britain and Ireland

appointed by the Board of Agriculture to inquire into the plague of field-voles

in Scotland in 1892. In the Minutes of Evidence appended to the Report of this

Committee, issued in 1893, will be found numerous statements, elicited by cross-

examination of the witnesses, which tend to prove beyond doubt that the Weasel is

the natural enemy of field-mice, and that no greater mistake could be made than to

destroy Weasels where mice or voles are numerous, and are likely to become a plague.’

In this report, which I have read, the most direct evidence is that of one

witness, David Glendinning, a shepherd, who, in reply to a question whether he had

ever seen a Weasel kill a vole, replied:

* Y e s ; about three weeks ago I came upon a small brown Weasel which had

killed five in one of the sheep-drains. I followed it up, and found it killing a

sixth. A week past on Sunday morning I came down a drain for 250 yards or so.

A Weasel had been before me, and there were twenty-two dead voles in the bottom.

I secured a specimen last night in order to show you the way a Weasel destroys

a vole. The blood is entirely drawn from behind the left ear. There is not

a bit of the vole marked otherwise, except by the tooth-marks on the head. All

those I have seen were killed in the same way.’

Mr. Harting thinks that there is a movement in favour of the Weasel, and

cites examples of the Duke of Buccleuch’s head keeper and others having received

orders not to molest them. These few cases of intelligent landlords are but a drop

in the bucket; the great mass of keepers, who pay no heed to advice, will go on

doing the same stupid things their fathers did before them to the end of the

chapter, unless laws are made and enforced.

Mice and voles are killed by the Weasel crushing their skulls, when it at

once eats the brains; but when larger animals are attacked the arteries of the neck

are first assaulted. It does not generally suck the blood of its victim, which dies

from nervous exhaustion. In nearly every instance after having obtained a hold

it flings its body over that of its victim and holds on despite mad rushes, falls,

and struggles. I was shooting in December 1902 with Mr. Fletcher at Dale Park,

near Arundel, and when posted forward under a steep bank about seventy yards

high I suddenly heard a rustling and commotion in the dry leaves on the top of

the hill. Next moment a half-grown rat bolted from a hole at full speed, immediately

followed by a Weasel. They had not run ten yards when the Weasel

gripped its victim, and squealing and struggling the two combatants came rolling

straight down the hill almost to my feet. I shot them both, for I needed a

Weasel as a model, and also wished to see how the rat had been seized. The

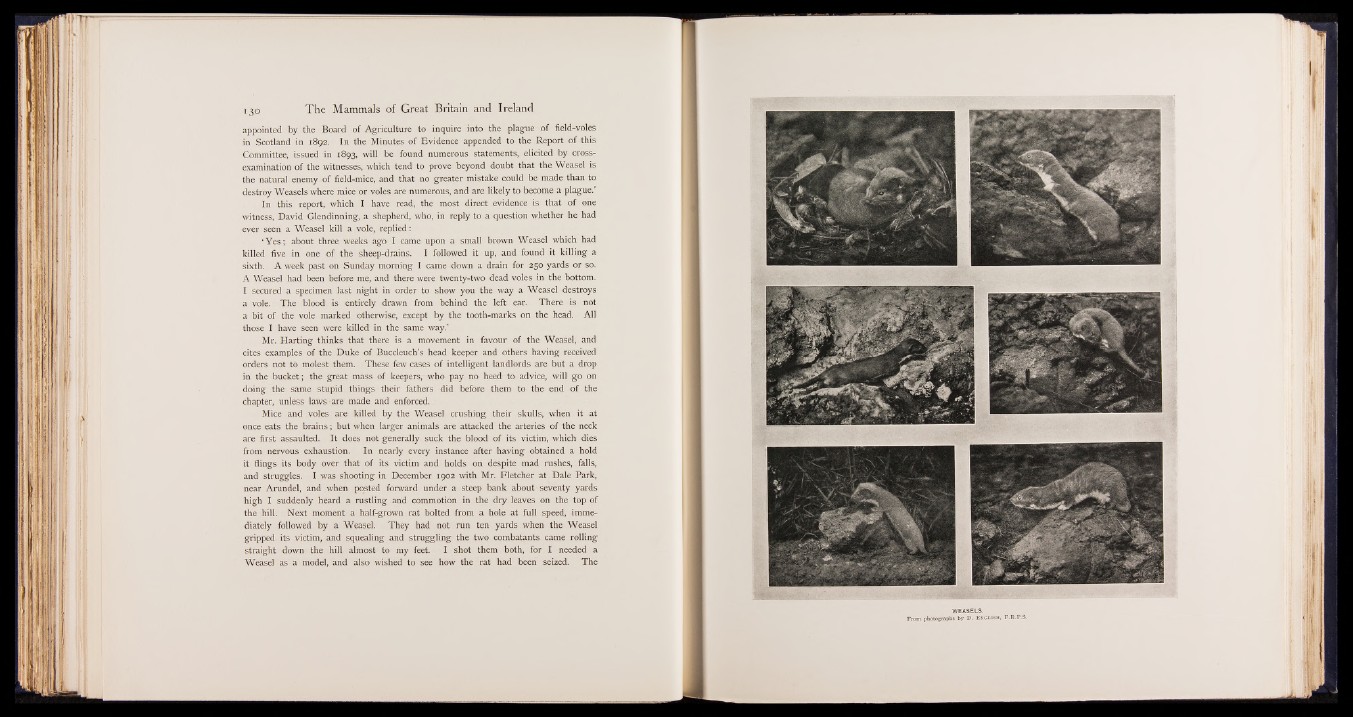

WEASELS.

From photographs by D. English, F.R.P.S.