island, and devour it there. To show how very rarely one sees an Otter, I have

only twice observed them on the Tay, where they , are common, although constantly

fishing there for twenty years. In fact, in some rivers, where there are always a

few, the inhabitants never suspect their existence.

The Otter will eat almost anything that swims and, when pressed for food,

such mammals as it can catch and k ill; it is fond of lob-worms and likes snakes.

In ponds and sluggish streams it lives largel^im eels, roach, dace, chub, loach,

miller’s-thumb, and jack, tench, and bream. Eels seem to be its favourite prey m

all waters, and it is said to eat them from the tail-end first. ‘ Many of these

fish,' says the late Captain Salvin, ‘ take to the sides upon seeing their enemy,

and’ he surprises, them under the banks, where they fondly imagine they are

hidden from view, and consequently safe.* ~ I have often heard Captain Salvin,

who knew a great deal about Otters, describe a struggle, which he witnessed

between a tame Otter and a large pike, 20 lb. i i 02, in weight, in a pond in

Stoke Park, near Guildford. After a desperate struggle the mammal, weighing

18 lb., landed its heavier antagonist.

In the swifter rivers of the north and in Ireland Otters kill large numbers of

both trout and salmon, but seem to prefer the latter fish. They can, without

doubt, chase and tire out a full-grown salmon. In the brothers : Stuart’s book

previously alluded tor there is a charming description of two Otters hunting in the

Beauly as witnessed by the elder brother John.

‘ I had sat in the oak for about half an hour, with my eyes fixed on the

stream, and my back against the elastic branch by which B was supported, and

rocked into a sort of dreamy repose, when. I was roused by a flash in the upper

pool, a ripple on its surface, and then a running swirl, and something that leaped,

and plunged, and disappeared. . . . Presently I saw two dark objects bobbing like

ducks down the rapid between the two pools, but immediately as they came near

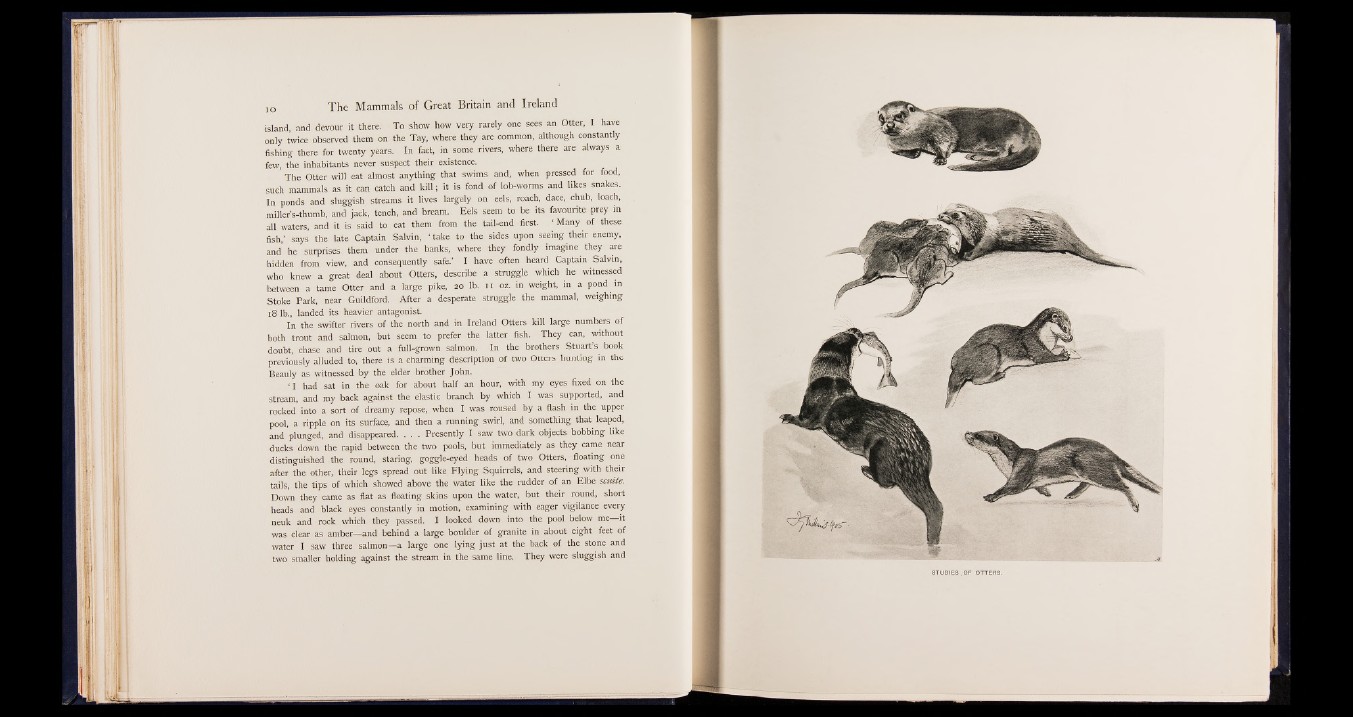

distinguished the round, staring, goggle-eyed heads of two Otters, floating one

after the other, their legs spread out like Flying Squirrels, and steering with their

tails-, the tips of which showed above the water like the rudder of an Elbe scuiie.

Down they came as flat as floating skins upon the water, but their round, short

heads and black eyes constantly in motion, examining with eager vigilance every

neuk and rock which they passed. I looked down into the pool below me—it

was clear as amber—and behind a large boulder of granite in about eight feet of

water I saw three salmon—a large one lying just at the back of the stone and

two smaller holding against the stream in the same line. They were sluggish and