is found all over the seaports of Southern Europe and North Africa, Egypt,

Palestine, Asia Minor, and Gilgit. A smaller variety known as the Tree Rat

{Mus rufescens) inhabits India, Ceylon, and Burma. The black variety {M. r. niger)

is known in the Black Sea ports, the Crimea, Asia Minor, North, South, Central,

and East Africa, but not in the forest regions. I have seen it in the Transvaal,

where it is the only variety.

In Sikkim and Nepaul there is a short-tailed form known as the Hill Rat

(Mus nitidus), and, in the Andaman Islands there is a curious variety with

spines in thé fur {Mus andamanensis) which Mr. O. Thomas considers specifically

identical with M. rattus.

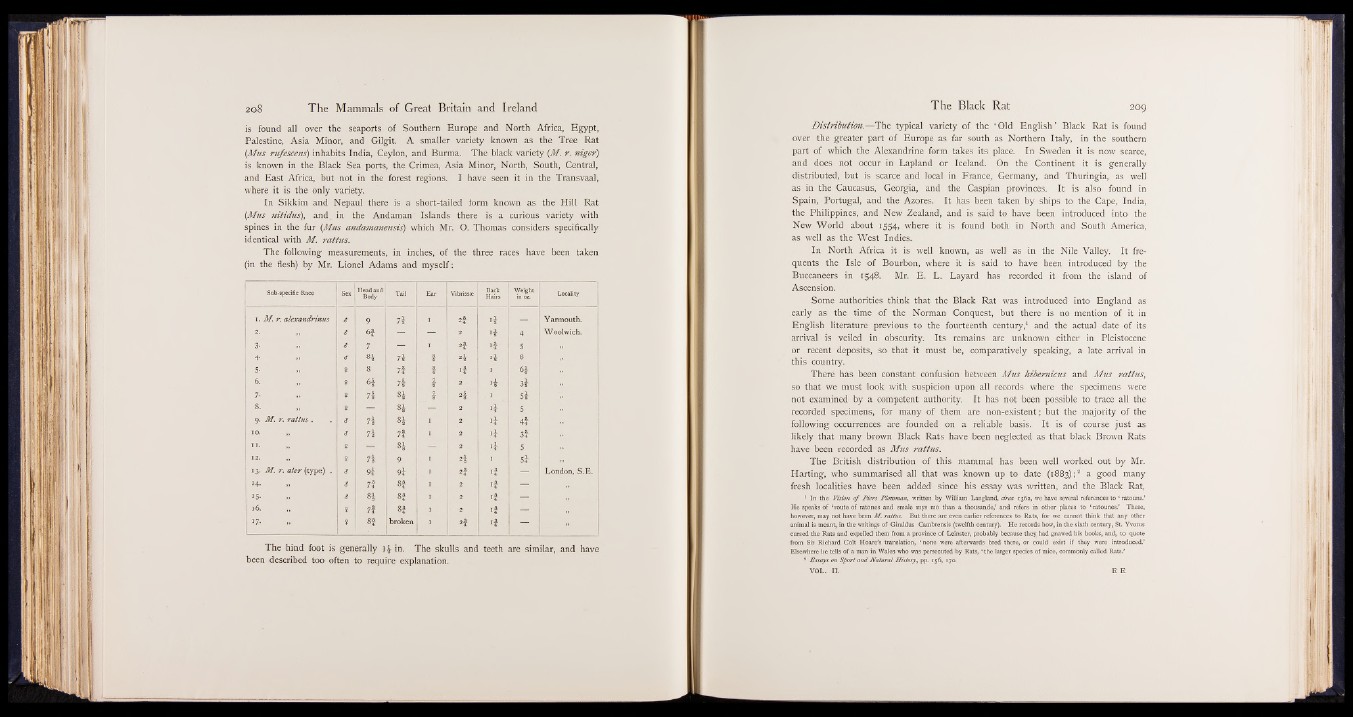

The following measurements, in inches, of the three races have been taken

(in the flesh) by Mr. Lionel Adams and myself:

Sub-specific Race Sex Head and

Body Tail Ear Vibrissa; Back

Hairs

Weight Locality

I. M. r. alexandrinus 8 • 9 7\ I 24 Yarmouth.

2 jjjB | 8 6f — — 2 1$ 4 Woolwich.

3- & 7 — I 2f i f 5

4- 8 8i 7i 4 *4 ■4 8

5- 9 8 7f - f ■ f I «4

6. „ 9 7t i 2 ■ i Ü

7- 9 74 «4 Ï I 54

8. 9 H — 2 ■4 5

9. M. r. rattus . 8 7% H I 2 ■4 4Ï

10. % 8 7i 7t I 2 ■4 3f

1SB „ 9 — «4 2 5

12. „ 9 7\ 9 i *4 I

13. M. r. ater (type) . 9\ 9i i 2f If London, S.E.

n 8 7f 8f I 2 i f — „

j H 8 H 8f I 2 i f — „

16. „ 9 7i 8f I 2 I& — „

17- 9 8f broken I 2f jS.

The hind foot is generally in. The skulls and teeth are similar, and have

been described too often to require explanation.

D istribution.—The typical variety of the ‘ Old English’ Black Rat is found

over the greater part of Europe as far south as Northern Italy, in the southern

part of which the Alexandrine form takes its place. In Sweden it is now scarce,

and does not occur in Lapland or Iceland, On the Continent it is generally

distributed, but is scarce and local in France, Germany, and Thuringia, as well

as in the Caucasus, Georgia, and the Caspian provinces. It is also found in

Spain, Portugal, and the Azores. It has been taken by ships to the Cape, India,

the Philippines, and New Zealand, and is said to have been introduced into the

New World about 1554, where it is found both in North and South America,

as well as the West Indies. .

In North Africa it is well known, as well as in the Nile Valley. It frequents

the Isle of Bourbon, where it is said to have been introduced by the

Buccaneers in 1548. Mr. E. L. Layard has recorded it from the island of

Ascension.

Some authorities think that the Black Rat was introduced into England as

early as the time of the Norman Conquest, but there is no mention of it in

English literature previous to the fourteenth century,1 and the actual date of its

arrival is veiled in obscurity. Its remains are unknown either in Pleistocene

or recent deposits, so that it must be, comparatively speaking, a late arrival in

this country.

There has been constant confusion between Mus hibemicus and Mus rattus,

so that we must look with suspicion upon all records where the specimens were

not examined by a competent authority. It has not been possible to trace all the

recorded specimens, for many of them are non-existent; but the majority of the

following occurrences are founded on a reliable basis. It is of course just as

likely that many brown Black Rats have been neglected as that black Brown Rats

have been recorded as Mus rattus.

The British distribution of this mammal has been well worked out by Mr.

Harting, who summarised all that was known up to date (1883);2 a good many

fresh localities have been added since his essay was written, and the Black Rat,

1 In the Vision o f Piers Plowman, written by William Langland, circa 1362, we have several references to ‘ ratouns.’

He speaks of ‘ route of ratones and smale mys mo than a thousande,’ and refers in other places to ‘ ratounes.’ These,

however, may not have been M. rattus. But there are even earlier references to Rats, for we cannot think that any other

animal is meant, in the writings of Giraldus Cambrensis (twelfth century). He records how, in the sixth century, St. Yvorus

cursed the Rats and expelled them from a province of Leinster, probably because they had gnawed his books, and, to quote

from Sir Richard Colt Hoare’s translation, ‘ none were afterwards bred there, or could exist if they were introduced.’

Elsewhere he tells of a man in Wales who was persecuted by Rats, ‘ the larger species of mice, commonly called Rats.’

1 Essays on Sport and Natural History, pp. 156, 170.