Iill 11 ill

« 111

m

| | jl

Ä l i i l l l 'l!

v | r

f l M i i •

i

IllillSlSMItliilll fi'!rii-«;;kjkh

;SS1

-

' 'iilTOiMiii#!''

MERLIN.

Falco JEsalon, Temm.

Le Faucon Em6rillon.

Although the Merlin is the least of the European birds of prey, still it possesses all the features which

characterize the most typical of its genus. Its undaunted courage and power of rapid flight embolden it

to attack birds far superior to itself in weight and magnitude ; hence, when hawking was a favourite pastime

with our ancestors, the Merlin was trained to the pursuit of partridges, woodcocks, snipes and larks ; and so

determined is its spirit, and so certain its aim, that it has not unfrequently been known to strike a partridge

dead, from a covey, with a single blow. Its flight is so low, that while skimming across large fallow or barren

grounds, it often appears to touch the earth with its wings. In the southern parts of the British Isles, it is

only a winter visiter, arriving at the departure of the Hobby; but Mr. Selby has fully proved that in the

northern parts it is stationary, and, unlike the Falcons in general, incubates on the ground, constructing a

nest among the heather. “ The number of the eggs,” says Mr. Selby, who has discovered their nests in these

situations in Northumberland, “ is from three to five, of a blueish white, marked with brown spots, principally

disposed at the larger end.”

The advanced state of ornithological science, as it regards the changes in plumage of our native birds,

enables us to affirm that the Stone Falcon (Falco Lithofalco, Auct.) is none other than the male Merlin in its

advanced stage of plumage, the bird undergoing changes in this particular which characterize more or less

the whole of the Falconidce. The uniform dark tints of the adult are not fully attained before the third year.

The Merlin is extensively spread over the countries of Europe; but M. Temminck informs us that it is

scarce in Holland, though it appears, from the accounts of other authors, to be met with in Germany in

winter. As regards its nidification, the above-mentioned naturalist differs materially from Mr. Selby in the

situation he assigns to it for the purpose of breeding, which he states to be trees, or the clefts of rocks:

the truth perhaps may be, that in different countries it may choose different localities, according as opportunities

may favour it.

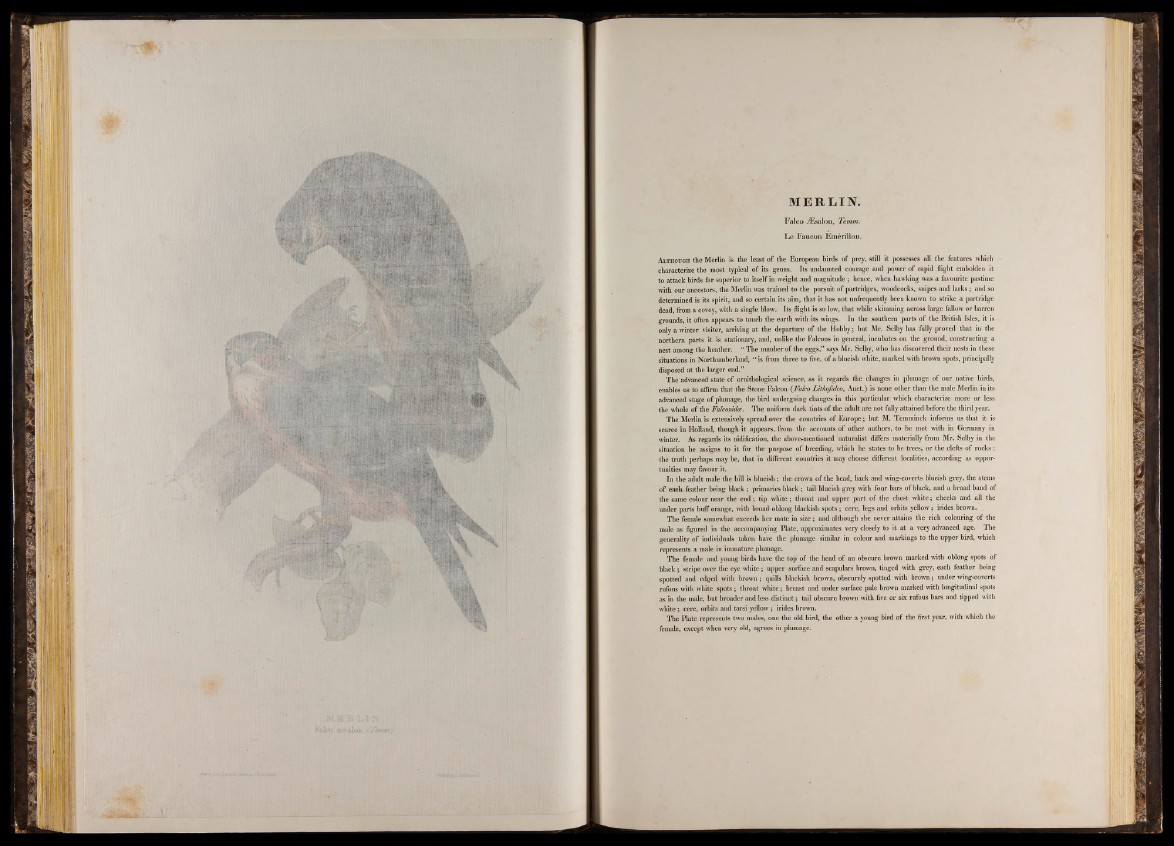

In the adult male the bill is blueish; the crown of the head, back and wing-coverts blueish grey, the stems

of each feather being black ; primaries black; tail blueish grey with four bars of black, and a broad band of

the same colour near die end; tip white; throat and upper part of the chest white; cheeks and all the

under parts buff orange, with broad oblong blackish spots ; cere, legs and orbits yellow; irides brown.

The female somewhat exceeds her mate in size ; and although she never attains the rich colouring of the

male as figured in the accompanying Plate, approximates very closely to it at a very advanced age. The

generality of individuals taken have the plumage similar in colour and markings to the upper bird, which

represents a male in immature plumage.

The female and young birds have the top of the head of an obscure brown marked with oblong spots of

black ; stripe over the eye white; upper surface and scapulars brown, tinged with grey, each feather being

spotted and edged with brown; quills blackish brown, obscurely spotted with brown; under wing-coverts

rufous with white spots ; throat white; breast and under surface pale brown marked with longitudinal spots

as in the male, but broader and less distinct; tail obscure brown with five or six rufous bars and tipped with

white ; . cere, orbits and tarsi yellow; irides brown.

The Plate represents two males, one the old bird, the other a young bird of the first year, with which the

female, except when very old, agrees in plumage.