CINEREOUS VULTURE.

Vultur cinereus, Linn.

Le Yautour noir.

T his, the largest of the European Vultures, offers to our notice, by the partially bare neck, open ears, curved

claws and powerful beak, a deviation from the true or more typical Vultures as restricted by modern authors,

the true Vultures having claws less curved, and a beak more lengthened and feeble, characters which

render them unable to seize and carry off living prey. This striking feature was not passed over by the

discriminating eye of Mr. Bennett while engaged in describing the Vultur auricularis of Daudin, a species

inhabiting Southern Africa, which in general form and structure strictly resembles the one under consideration.

In “ The Gardens and Menagerie of the Zoological Society delineated,” that gentleman intimates that in his

opinion the bird he has described, from a fine living example in the Society*s Gardens, would be found to

possess characters sufficiently prominent and different from the rest of the Vultures to form the type of a

new genus. Although the Cinereous Vulture has not that longitudinal fold of the skin which is so

prominent a feature in the Vultur auricularis, still we should regard that more as a specific character than as

having any influence oyer its natural economy; and we fully concur in Mr. Bennett’s views in considering a

further subdivision of the family to be necessary. The two birds in question, with the Vultur pondicerianus as

a type, would constitute a very natural division. We refrain ourselves from assigning a generic name, or

from entering more fully into the subject, as we are aware that M. Temminck is at this moment paying

strict attention to this highly interesting family; and we have no doubt that with his discerning views and

profound knowledge of Ornithology, he has long ere this observed the characters alluded to.

The European habitat of the Cinereous Vulture is the vast forests of Hungary, the mountainous districts

of the Tyrol, the Swiss Alps, the Pyrenees, and the middle of Spain and Italy; it is seen also occasionally

in other places.

M. Temminck states that its food consists of dead and putrid animals, never living ones, of which it is much

afraid, even the smallest appearing to excite fear; but Bechstein informs us that “ in winter it is chiefly seen

in the plains, where it attacks sheep, hares, goats, and even deer. The farmers suffer severely from this bird,

as it will frequently pick out the eyes of sheep; but as it is not a very shy species, it gives the huntsman some

advantage, added to his being well paid for shooting so destructive an enemy.”—(Latham’s General History of

Birds, vol. i. p. 23.)

Of its nidification and eggs nothing is known.

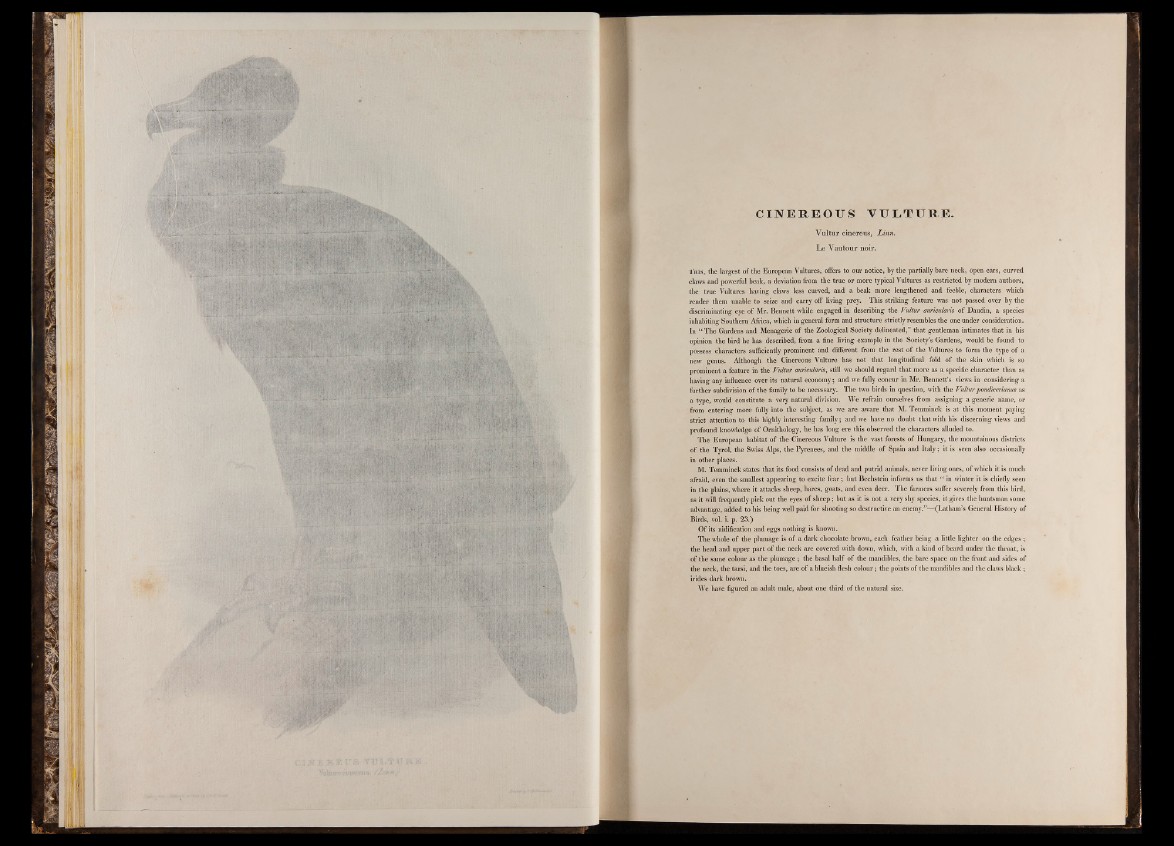

The whole of the plumage is of a dark chocolate brown, each feather being a little lighter on the edges ;

the head and upper part of the neck are covered with down, which, with a kind of beard under the throat, is

of the same colour as the plumage ; the basal half of the mandibles, the bare space on the front and sides of

the neck, the tarsi, and the toes, are of a blueish flesh colour; the points of the mandibles and the claws black;

irides dark brown.

We have figured an adult male, about one third of the natural size.