especially direct the attention to the caves with which those volcanic islands abound. The

chief agents in the destruction of the brevipennate birds were probably the run-away

negros, who for many years infested the primasval forests of those islands, and inhabited

the caverns, where they would doubtless leave the scattered bones of the animals on which

they fed. Here, then, may we more especially hope to find the osseous remains of these

remarkable animals.

Should any copies of this work find their way to Mauritius or Bourbon, they may

perhaps incite the lovers of knowledge in those islands to investigate further the subject

which has been diligently, but imperfectly, pursued in this volume. And I shall feel rewarded

for the trouble it has cost, if my researches into the history and organization of these birds,

aided by the anatomical investigations which Dr. Melville has introduced into the second

part of the work, shall' have rescued these anomalous creatures from the domain of Fiction,

and established their true rank in the Scheme of Creation.

END OF PART I.

Postscript to Part I.

The foregoing sheets had been printed some time, and the second part of this work had been unavoidably

delayed by the great attention which the osteologicai plates and descriptions required, when I was led to

some additional sources of information which demand notice.

The first of these is a rare edition of Bontekoe’s Voyage, kindly communicated to me by Dr. Bandine],

the Bodleian Librarian, entitled “ Journael van de acht-jarige avontuerlijcke Reyse van Willem Ysbrantsz

Bontekoe van Hoorn, gedaen nae Oost-Indien,” published in 4to at Amsterdam, by Gillis Joosten

Zaagman. There is no date, but from a narrative introduced at the end, it must be subsequent (probably

only by a year or two) to 1646. The narrative is nearly a verbatim version of the other Dutch editions of

Bontekoe (noticed at p. 57 supra), and the only variation of text which concerns us, is in the statement

that the underside of the Dodo dragged along the ground, which is here qualified thus:—“ sleepte haer

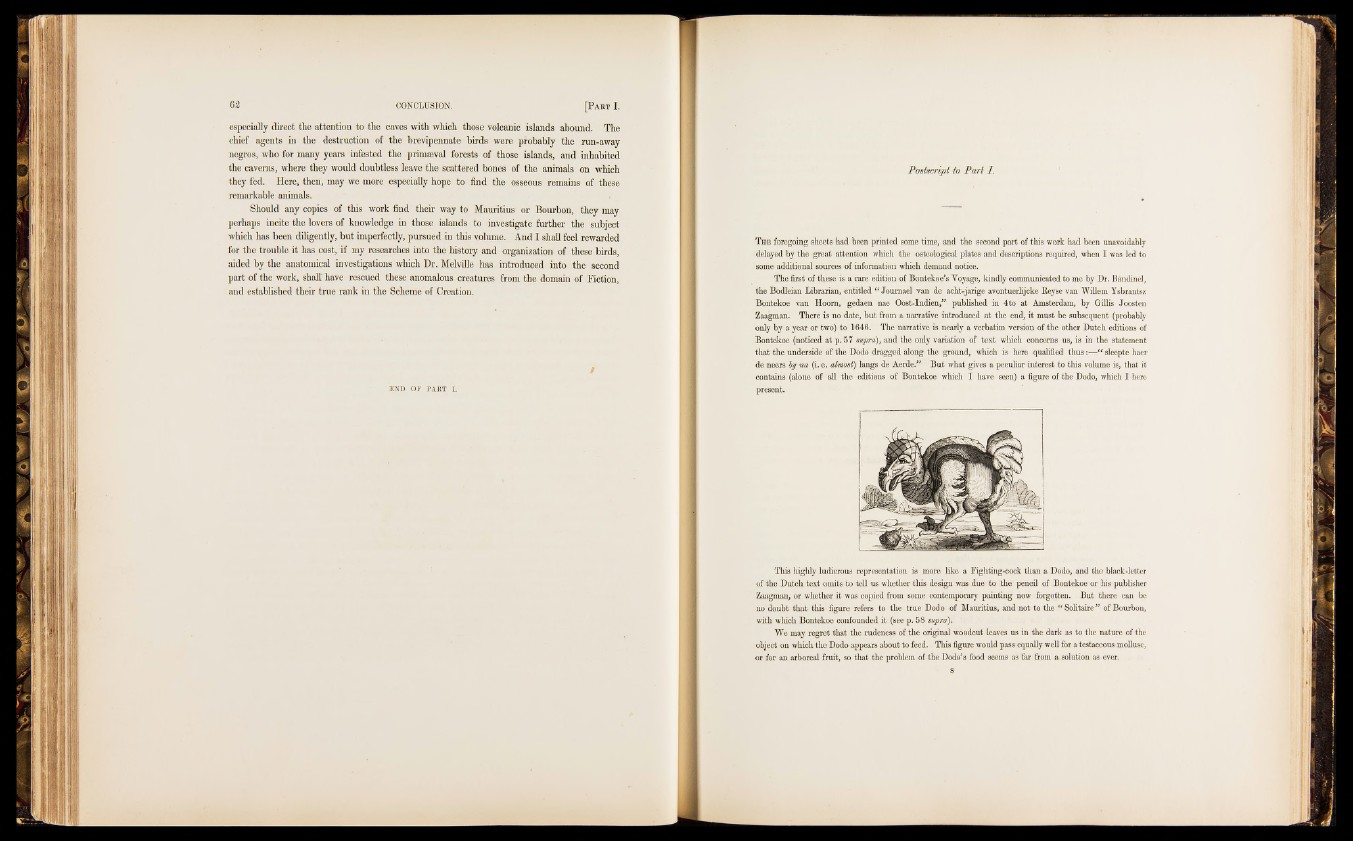

de neers by na (i. e. almost) langs de Aerde.” But what gives a peculiar interest to this volume is, that it

contains (alone of all the editions of Bontekoe which I have se.en) a figure of the Dodo, which I here

present.

This highly ludicrous representation is more like a Fighting-cock than a Dodo, and the black-letter

of the Dutch text omits to tell us whether this design was due to the pencil of Bontekoe or his publisher

Zaagman, or whether it was copied from some contemporary painting now forgotten. But there can be

no doubt that this figure refers to the true Dodo of Mauritius, and not to the “ Solitaire ” of Bourbon,

with which Bontekoe confounded it (see p. 58 supra).

We may regret that the rudeness of the original woodcut leaves us in the dark as to the nature of the

object on which the Dodo appears about to feed. This figure would pass equally well for a testaceous mollusc,

or for an arboreal fruit, so that the problem of the Dodo's food seems as far from a solution as ever.

s