^ IKTIiODUCTIOIi.

species {Urosti,,ma) in which it docs not obtain, and imvhich male, fertile female, and gall

flowers arc contained in the same receptacle. In this group the difference in strncture

in the eai-Iy stages between gall and fertile female flowers is very slight, and in some

eases I could find no diflerence whatever. And ei-en the ripe aehenes of the fertile

females are in many oases nndistingnishablo externally from the ovaries containing far

advanced pnpio, and it is only by catting them open that they can be recognised. As

regards the relation in this group of Urostiana of the male flowers to the fertile female

and gall flowers, there are two types of an-augement. In one set of species (of which

2'. Bagdenm and tmiunhsa are good examples) the male flowers are comparatively few in

number, and are oonflned to a zone at tho apei of the receptacle, just under the ostiolar

scales; while in another set the male flowers are intermixed ivith the fertile female and

gall flowers over the whole surface of the interior of the receptacle.

A thir-d small gTonp (Si/trceim) has neater flowers mixed with the fertile females in

one set of receptacles; while the other set of recoptaoles contams only male and gall

flowers. And a fom-th group (which I have named Pakemmrflii) has male flowers which,

in adtKtion to an anther, contain an insect-attaeked or gall pistil. These pseudo-hermaphrodite

flowers are confined to the sub-ostiolar zone, tho remainder of the receptacle

being occupied by gall flowers: while perfect female flowers occur in a distinct set of

receptacles and are unaccompanied by any trace of male or gall flowers.

I t appears to me that, in the pecuharities in the strncture and arrangement of the flowers

-which I have above described, the evolutionary history of the genus F k m may to some extent

b e ti-aced. I have therefore ventured to arrange the Indo-Malayan species into two great

groups, and to divide the second of these great groups into three sub-groups, aeeording

to their presumed seniority. Believing that hermaphroditism is an archaic and primitive

condition from which the genus is in process of deKvery, I look on its persistence, even in

an imperfect form, as an indication of age. I have therefore separated off the ten species

in which I find it regularly to occur into a distinct group. Of this group pseudohermaphroditism

is the diagnostic mark, and to the section which these ten species form

I have given the name Palaianwrfhe. It is true that in the whole of these ten species

t h e pseudo-hermaphrodite flowers are confined to the same receptacles as tho gall flowers,

while the perfect females are confined to a disthrct set of receptacles in which there is

no trace of either males or galls, and that the reccptaclcs are thus practically dicecious.

Still it appears to me that the persistence of the rudimentary female organ in the male

flowers mast be taken as indicating a more primitive condition than the enclosure in the

same receptacle .of strictly unisexual male and female flowers (the ar-rangement obtaining

in Unstigma). These ten species being disposed of in a gi-oup by themselves, I have

formed the remaining species of Indo-Malayan F-kus into a group characterised by

unisexual flowers. And that group I have divided mto three sub-groups, aceordinn- as

the receptacles are moncecious, pseudo-moncccious, or practically diojcious, the practically

IKTBODUCTIOK. XI

diojcious sub-group being again subdivided into sections which are founded on the

nmnber of the stamens and the situation of the receptacles. Tor five of the seven

sections into which I have thus thrown the Indo-Malayan species, I have adopted as

sectional designations words pre,dously in use as sectional or subgeneric names. For the

fii-st section, as already stated, I have invented a new name, which indicates what I

believe to bo its position in the evolution of the genus; and for tho seventh I have also

invented a new name, indicating its nemes s in point of evolution. The ara-angement is

as follo-ws;—

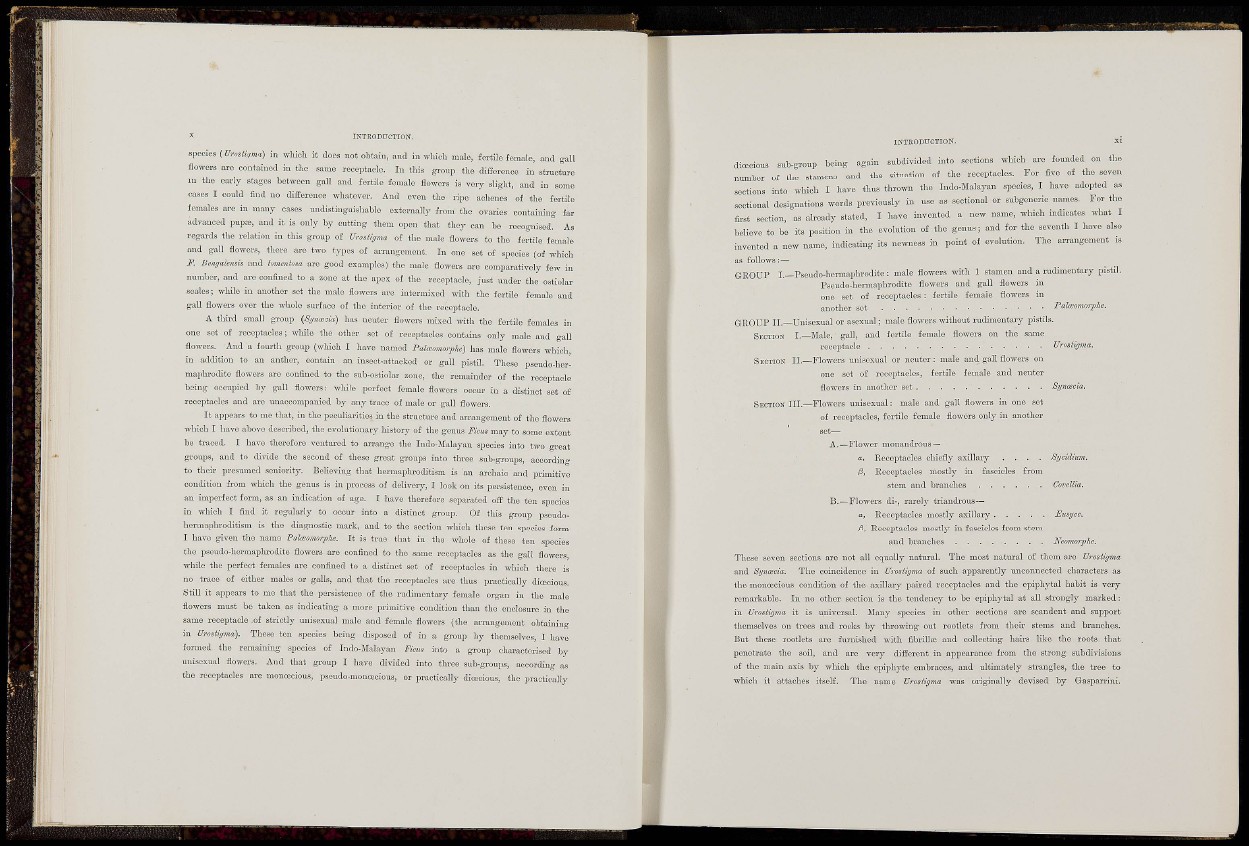

GROUP I.—Pseudo-hermaphrodite: male flowers with 1 stamen and a i-udimentary pistil.

Pseudo-hermaphrodite flowers and gall flowers in

one set of receptacles: fertile female flowers in

another set

GHOUP II. Unisexual or asexual; male flowers without rudimentary pistils.

SECTION I.—Male, gall, and fertile female flowers on the same

receptacle Urostigma.

SECTION II.—Flowers unisexual or neuter : male and gall flowers on

one set of receptacles, fertile female and neuter

flowers in another set

SECTION I I I .—Flower s unisexual: male and gall flowers in one set

of receptacles, fertile female flowers only in another

A.—Flower monantlrous —

0-, Receptacles chicfly axillary . . . . Sycidium.

/3, Receptacles mostly in fascicles from

stem and branches Covdlia.

B.—Flowers di-, rare!}' triandrous—

a, Receptacles mostly axillary Eusycc.

/S, Receptacles mostly in fascicles f rom stem

and brandies Neomorphe.

Hiese seven sections are not all equally natm-al. The most natural of them are Urostigma

and Synxcia. The coincidence in UrosUgma of such apparently miconnected characters as

t h e monoscious condition of the axillary paired receptacles and the epiphytal habit is very

remai'kablo. In no other section is the tendency to be epiphytal at all strongly marked:

in UrosUgma it is universal. JIany species in other sections are scandent and support

themselves on trees and rocks by throwing out rootlets from their stems and branches.

But these rootlets ai-e furnished with fibrillaj and collecting hairs like the roots that

penetrate the soil, and are very different in appearance from the strong subdivisions

of the main axis by wliich the epiphyte embraces, and ultimately strangles, the tree to

which it attaches itself. The name Vrosiigma was originally devised by Gasparrini.