ico, many lovers of peace and seekers for prosperity

betook themselves to this tranquil isle. Thus it

came about that after a century or two of neglect

and solitude, it was one of the most populous and

thriving of the Antilles. Of the progress of population

there is no accurate record, but the last Spanish

census, taken in 1887, made it 799,000, of which

475,000 was white and 324,000 black and coloured,”

or mixed. I t was estimated in 1898 at

over 900,000, nearly two thirds Spanish and creoles

of European descent, while the mulattoes outnumbered

the negroes.

Puerto Rico during the comparatively short history

of its development was rather submissive to

Spanish rule, partly because that rule was somewhat

milder than in Cuba and partly because resistance was

hopeless. In 1820, when the spirit of revolution was

rife and there were many refugees from countries in

which it was raging, an uprising was attempted even

here, and as Spain had her hands full at the time, the

insurrectionary movement was kept alive until 1823,

when she had no difficulty in reasserting her authority.

A n attempt at revolt was made in 1867, when

the Cuban plots were fermenting, but it was promptly

suppressed, with the help of an alarming earthquake.

In fact, the people had little chance to arm or to

organise; there were no mountain fastnesses in which

to take refuge; and it required but few Spanish

soldiers to keep them in subjection.

In 1869, the Spanish Cortes decreed a constitution

to Puerto Rico, which made it in form a province

of Spain, instead of a colonial dependency. It

was to be represented in the Cortes by regular

provincial deputies, elected upon the same conditions

of suffrage as those prevailing in Spain. T he

governor-general was to be the resident representative

of the sovereign power. He was at once the

captain-general of the armed forces and the chief

administrative officer. A s civil governor he was

president of the supreme tribunal of justice and the

head of an administrative council appointed at

Madrid, having supervision of civil, military, and

ecclesiastical affairs; but the fiscal interests of the

government were in charge of a specially appointed

officer, called an “ Intendant. ” There was a bishop,

appointed by the Crown, with the approval of the

Pope, and made subordinate to the archbishop of

Santiago de Cuba. T he judicial system was like

that of Cuba, with an Audiencia Real, district courts,

and local magistrates called alcaldes. These were

all appointed by the central government, and the

provincial autonomy was a mere matter of form.

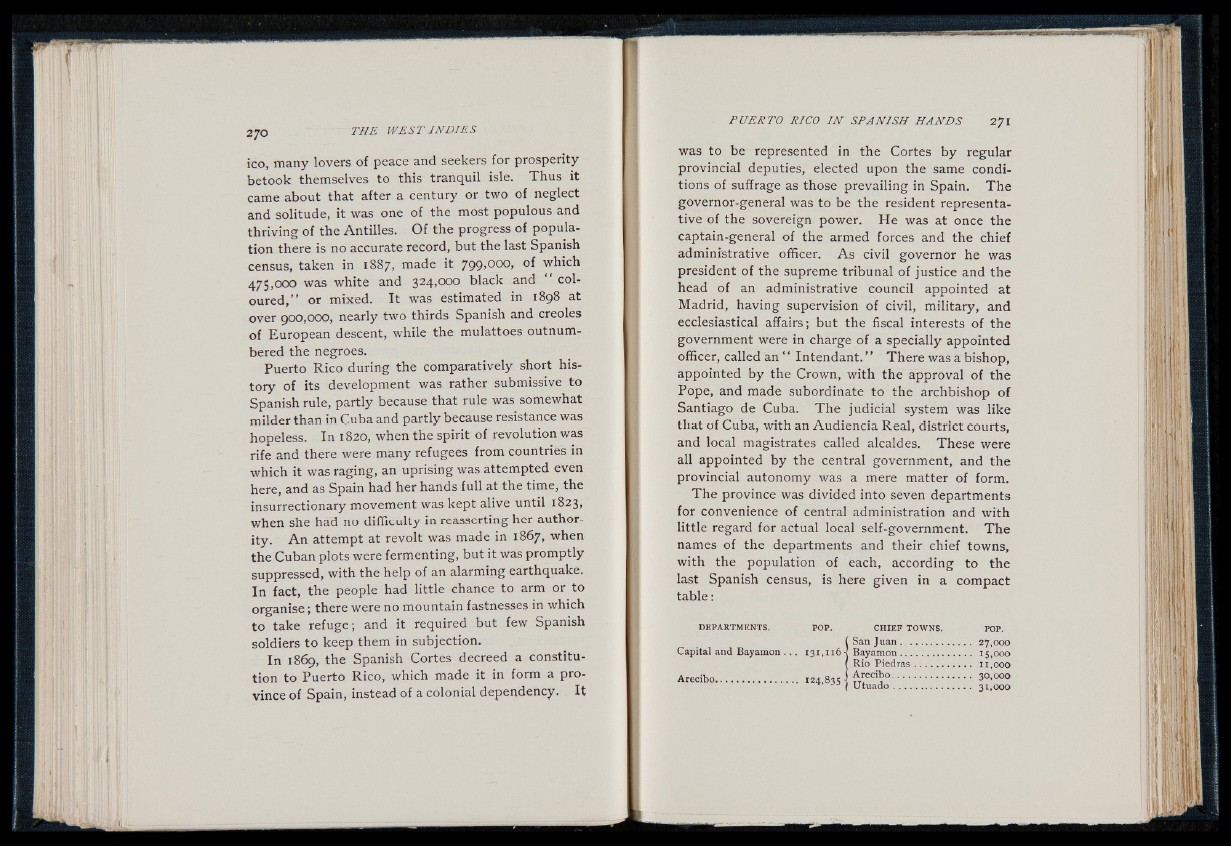

T he province was divided into seven departments

for convenience of central administration and with

little regard for actual local self-government. The

names of the departments and their chief towns,

with the population of each, according to the

last Spanish census, is here given in a compact

ta b le :

DEPARTMENTS. POP. CHIEF TOWNS. POP.

jSan Juan........................ 27,000

Bayamon........................ 15,000

Rio Piedras................... 11,000

Arecibo............................. 124,835 \ 30,ooo

J / Utuado........................ 31,000