The height of this point is a little less than that

at Matua, and all the way from Fort de Kock to this

place I have been able to keep in sight the remains

-of the plateau which begins on the south with

the col between the Singalang and Merapi. The

horizontal layers, that once filled the whole valley

west of us, have been carried away by the streams

until only a narrow margin is left on the Barizan,

and its parallel chain; it forcibly reminds me of the

terraces seen along the upper part of some of our

own ISTew-England rivers—-for instance, those in the

upper part of the Connecticut Valley.

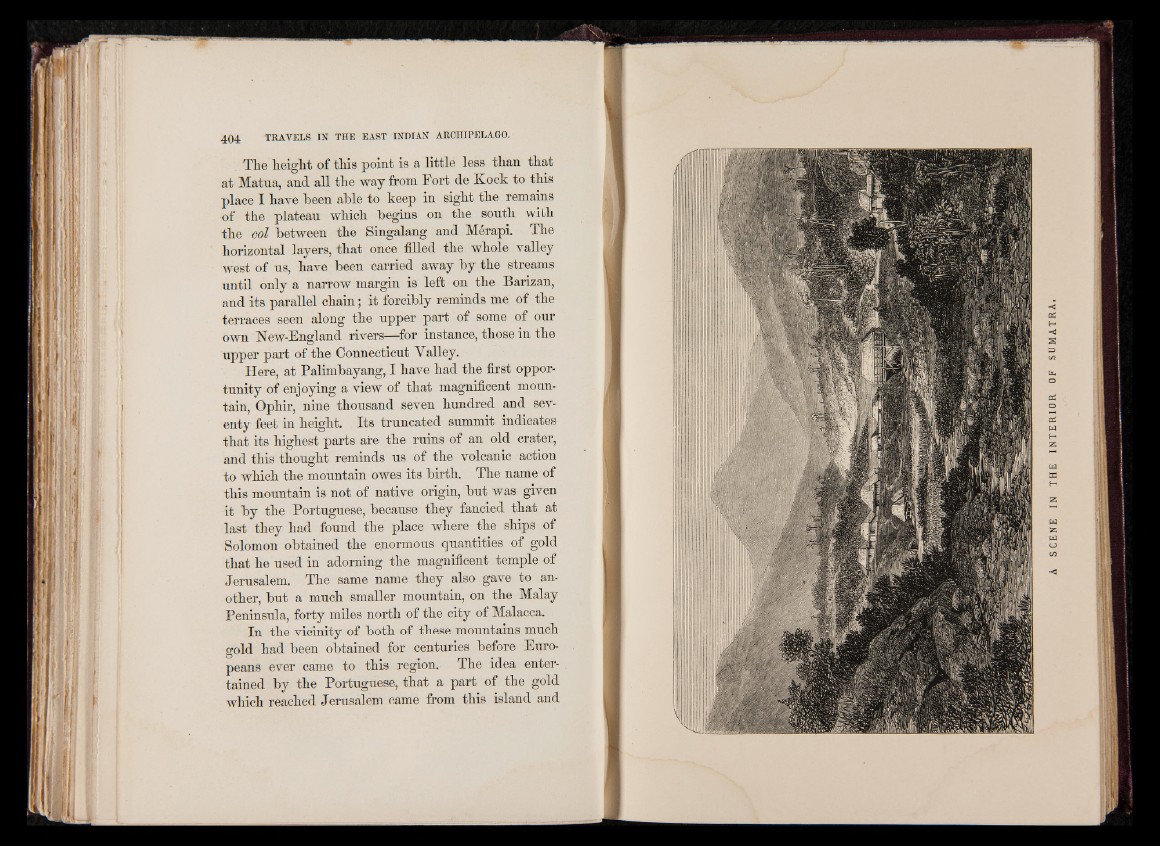

Here, at Palimbayang, I have had the first opportunity

of enjoying a view of that magnificent mountain,

Ophir, nine thousand seven hundred and seventy

feet in height. Its truncated summit indicates

that its highest parts are the ruins of an old crater,

and this thought reminds us of the volcanic action

to which the mountain owes its birth. The name of

this mountain is not of native origin, but was given

it by the Portuguese, because they fancied that at

last they had found the place where the ships of

Solomon obtained the enormous quantities of gold

that he used in adorning the magnificent temple of

Jerusalem. The same name they also gave to another,

but a much smaller mountain, on the Malay

Peninsula, forty miles north of the city of Malacca.

In the vicinity of both of these mountains much

gold had been obtained for centuries before Europeans

ever came to this region. The idea entertained

by the Portuguese, that a part of the gold

which reached Jerusalem came from this island and