was nearest the top, and asked him if I could go

down there, to which, of course, he answered yes, as

most people do when they do not know what to say,

and must give some reply.

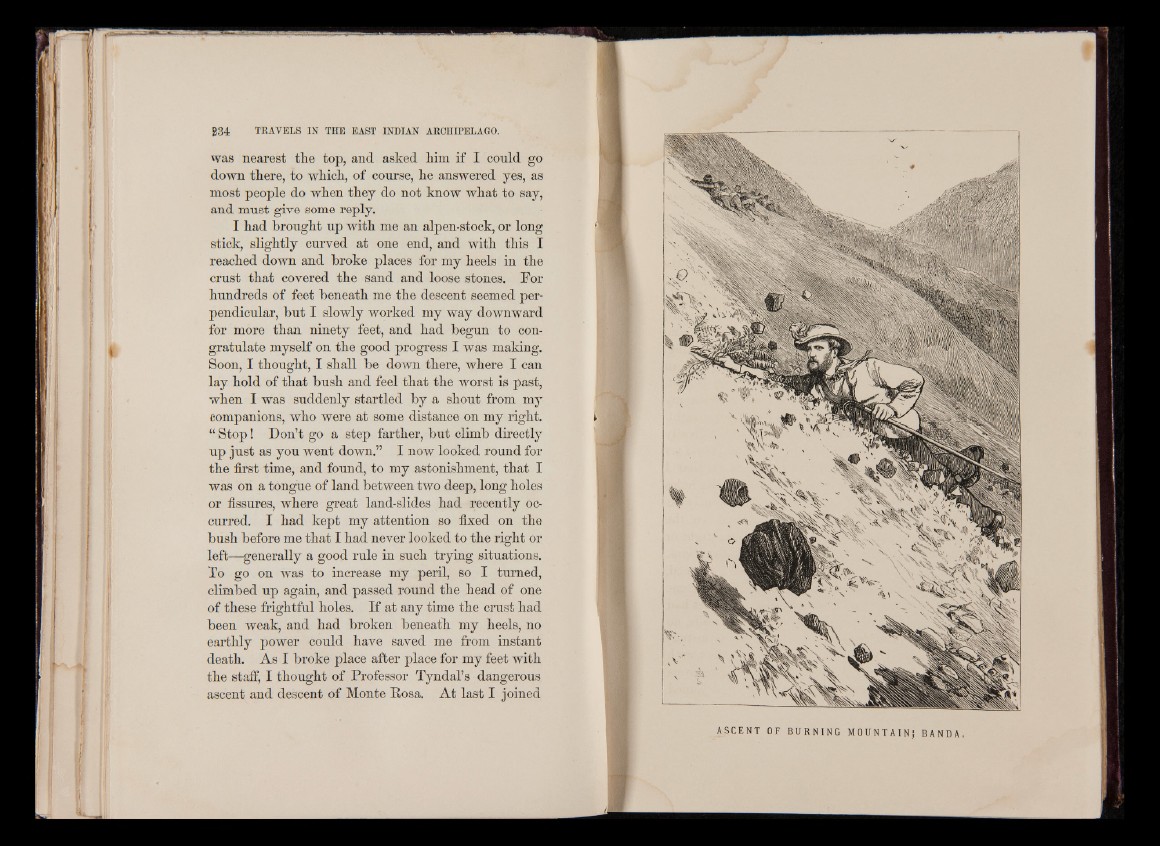

I had brought up with me an alpen-stock, or long

stick, slightly curved at one end, and with this I

reached down and broke places for my heels in the

crust that covered the sand and loose stones. For

hundreds of feet beneath me the descent seemed perpendicular,

but I slowly worked my way downward

for more than ninety feet, and had begun to congratulate

myself on the good progress I was making.

Soon, I thought, I shall be down there, where I can

lay hold of that bush and feel that the worst is past,

when I was suddenly startled by a shout from my

companions, who were at some distance on my right.

“ Stop! Don’t go a step farther, but climb directly

up just as you went down.” I now looked round for

the first time, and found, to my astonishment, that I

was on a tongue of land between two deep, long holes

or fissures, where great land-slides had recently occurred.

I had kept my attention so fixed on the

bush before me that I had never looked to the right or

left—generally a good rule in such trying situations.

To go on was to increase my peril, so I turned,

climbed up again, and passed round the head of one

of these frightful holes. If at any time the crust had

been weak, and had broken beneath my heels, no

earthly power could have saved me from instant

death. As I broke place after place for my feet with

the staff, I thought of Professor Tyndal’s dangerous

ascent and descent of Monte Rosa. At last I joined