te eth; “ had it not been that I know that farther down

where I intend going iron in all likelihood will not be

found, and consequently no native blacksmiths, I would

leave you to yourself.”

Though I had to pocket my pride, I was determined to

see this primitive artificer at work; so I continued to give

him beads, and as he called for more doled them out by

degrees, thus removing gradually the symptoms of disappointment,

until at length his countenance cleared, and it

became apparent that his heart was healed.

I then took possession of the stolen assegai, and the old

man proceeded to work. Negotiating in this fashion took

up a very long time, particularly as I was becoming a more

adroit trader, and although I had given him beads many

times, the aggregate was not very great.

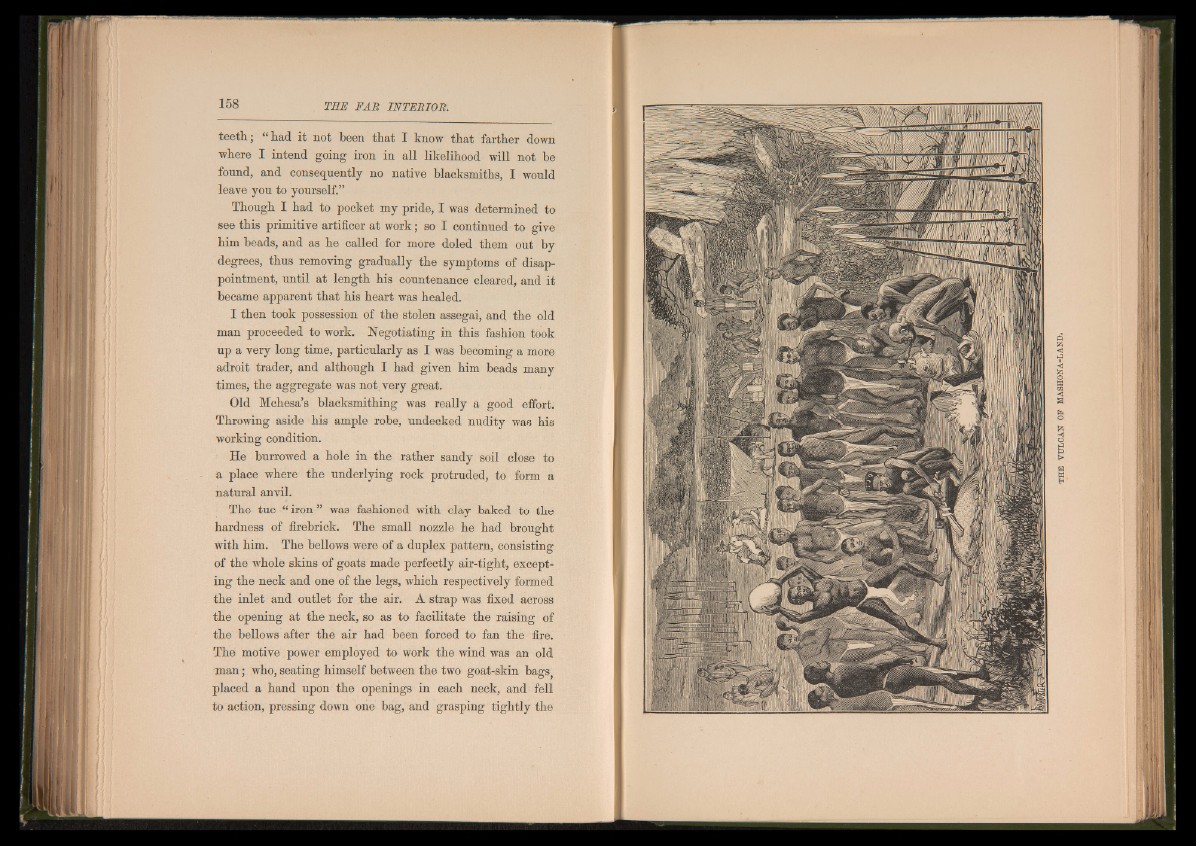

Old Mchesa’s blacksmithing was really a good effort.

Throwing aside his ample robe, undecked nudity was bis

working condition.

He burrowed a hole in the rather sandy soil close to

a place where the underlying rock protruded, to form a

natural anvil.

The tue “ iron” was fashioned with clay baked to the

hardness of firebrick. The small nozzle he had brought

with him. The bellows were of a duplex pattern, consisting

of the whole skins of goats made perfectly air-tight, excepting

the neck and one of the legs, which respectively formed

the inlet and outlet for the air. A strap was fixed across

the opening at the neck, so as to facilitate the raising of

the bellows after the air had been forced to fan the fire.

The motive power employed to work the wind was an old

man; who, seating himself between the two goat-skin bags,

placed a hand upon the openings in each neck, and fell

to action, pressing down one bag, and grasping tightly the