thus a portion o fth e finest land is rendered

useless. The cultivated slopes at the base

of the mountains are subject to be buried

under eboulements*, when the rocks above

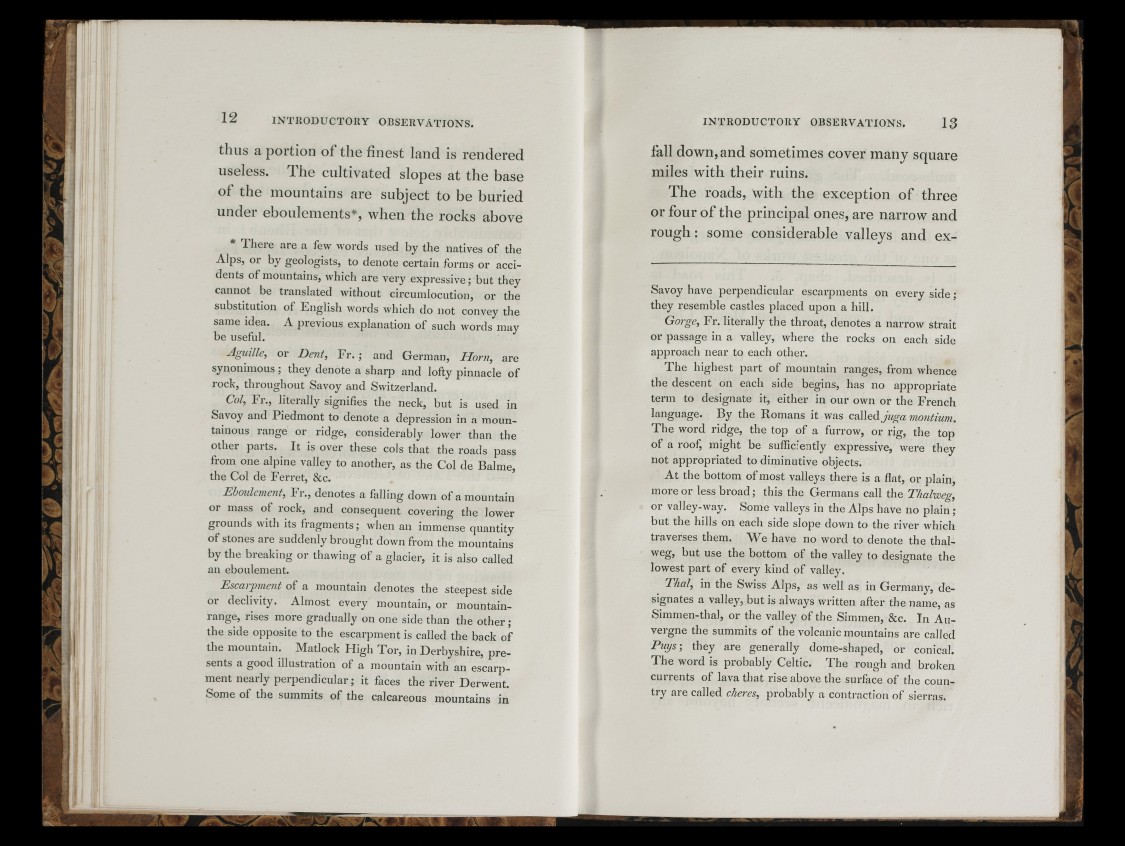

* There are a few words used by the natives of the

Alps, or by geologists, to denote certain forms or accidents

of mountains, which are very expressive; but they

cannot be translated without circumlocution, or the

substitution of English words which do not convey the

same idea. A previous explanation of such words may

be useful.

Aguille, or Dent, Fr. ; and German, Horn, are

synonimous; they denote a sharp and lofty pinnacle of

rock, throughout Savoy and Switzerland.

Col, Fr., literally signifies the neck, but is used in

Savoy and Piedmont to denote a depression in a mountainous

range or ridge, considerably lower than the

other parts. It is over these cols that the roads pass

from one alpine valley to another, as the Col de Balme,

the Col de Ferret, &c.

Eboulement, Fr., denotes a falling down of a mountain

or mass of rock, and consequent covering the lower

grounds with its fragments; when an immense quantity

of stones are suddenly brought down from the mountains

by the breaking or thawing of a glacier, it is also called

an eboulement.

Escarpment of a mountain denotes the steepest side

or declivity. Almost every mountain, or mountain-

range, rises more gradually on one side than the other ;

the side opposite to the escarpment is called the back of

the mountain. Matlock High Tor, in Derbyshire, presents

a good illustration of a mountain with an escarpment

nearly perpendicular; it faces the river Derwent.

Some of the summits of the calcareous mountains in

fall down, and sometimes cover many square

miles with their ruins.

The roads, with the exception of three

or four of the principal ones, are narrow and

rough: some considerable valleys and ex-

Savoy have perpendicular escarpments on every side ;

they resemble castles placed upon a hill.

Gorge, Fr. literally the throat, denotes a narrow strait

or passage in a valley, where the rocks on each side

approach near to each other.

The highest part of mountain ranges, from whence

the descent on each side begins, has no appropriate

term to designate it, either in our own or the French

language. By the Romans it was caWeájuga montium.

The word ridge, the top of a furrow, or rig, the top

of a roof, might be sufficiently expressive, were they

not appropriated to diminutive objects.

At the bottom of most valleys there is a fiat, or plain,

more or less broad ; this the Germans call the Thalweg,

or valley-way. Some valleys in the Alps have no plain ;

but the hills on each side slope down to the river which

traverses them. We have no word to denote the thalweg,

but use the bottom of the valley to designate the

lowest part of every kind of valley.

Thai, in the Swiss Alps, as well as in Germany, designates

a valley, but is always written after the name, as

Simmen-thal, or the valley of the Simmen, &c. In Auvergne

the summits of the volcanic mountains are called

Puys] they are generally dome-shaped, or conical.

The word is probably Celtic. The rough and broken

currents of lava that rise above the surface of the country

are called cheres, probably a contraction of sierras.

m

1