tribe. Epimachus, in which he also includes the species o f Ptiloris and Seleucides, he makes his second

subfamily of the Upupidæ (of the tribe Tenuirostres in the order Passeres). Sericulus is placed in the fourth

subfamily, Oriolinæ, of the' Turdinæ, tribe Dentirostres ; while Chlamydodera, Ptilonorhynchus, and Astrapia are found

in the first subfamily of tibe Stumidæ, tribe Comrostres. Schlegel extends the Paradiseidæ further than I am

able to follow. He places it in his Coraces, and comprises all his genera in one subfamily, Paradiseæ. The

genera are:__Paradisea, Epimachus, Sericulus, Oriolus, Ptilonorhynchus, Chalybeus, Cracticus and Lycocorax, arranged as

enumerated, and containing all the species composing this Monograph, and some more, but having little affinity

with the Paradiseidæ, that I am able to discover. Cabanis, in the ‘Museum Heineanum,’ places this family among

the Oscines, ™«1ring Sericulus follow close after Oriolus o f the Oriolinæ, and separated from Chlamydodera and

Ptilonorhynchus (also placed in the same subfamily) by Sphecotheres. The second subfamily (Paradiseinæ) contains the

true Birds of Paradise; while the third (Epimachinæ) comprises the species allotted to it in the present work.

Bonaparte has divided the members o f the Paradiseidæ, as here restricted, to a greater degree thaù almost any

other author. Epimaehidæ and Paradiseidæ constitute respectively the fifty-eighth and fifty-ninth families o f his

Passeres, tribe Volucres ; Sericulus is placed in the family Oriolidæ, Phonygama in the Garrulidæ, as are dso

Chlamydodera and Ptilonorhynchus ; and Astrapia and Paradigalla are found in the family Stumidæ. Blyth, in his

I Catalogue of Birds in the Museum of the Asiatic Society,’ makes the Paradiseidæ a subfamily (Paradiseinæ) of

the Corvidæ and includes, besides Paradisea apoda, papuana, and sanguinea and (Cicinnurus) regius and paradiseus

(Ptiloris), Sericulus (Chrysocephalm) melinus, Ptilonorhynchus holosericeus (violaceus), P. Smithi (Æluroedus crassirostris),

and Corcorax leucopterus—thus, with the exception of the last species, agreeing mainly with the arrangement I

have made of the family in the present work.

It will thus be seen that authors generally have considered that the species which I have deemed to compose

the Paradiseidæ belonged to many families and orders, but that they have in no wise agreed among themselves as

to the proper disposition o f the species. It is often a matter o f great difficulty to give an animal its right position

in the natural system; and an acceptable arrangement of the members in any group, can only be effected after a

careful investigation and comparison have been made as to their natural affinities in both their anatomical structure

and outside covering ; and this, unfortunately is in very many instances impossible, the necessary material not being

available to enable such studies to be carried out. Animals that present no outward similarity, so far as their

appearance goes, often prove their affinities to each other by the exhibition o f the same habits ; and when these last

are unusual and cause their possessors to be conspicuous members of the fauna in the district which they inhabit,

it would be very unwise to pass them over as of no consequence in the animal’s systematic position, and to regard

them only as resulting from eccentric dispositions bestowed for no special purpose. In restricting the Paradiseidæ

to the species contained in this work, I have been influenced both by their osteological affinities and in the case of

such genera as compose my third subfamily, Tectonarchinæ, by their possessing the same extraordinary habit o f bower-

building, from which they have derived their trivial name. Some o f the reasons which have induced me to consider

the Tectonarchinæ members o f this family are the following:—Sericulus, whose single species is unquestionably

a Bower-bird, possesses on the head the peculiar, firm, upright, and closely pressed feathers which constitute

one of the chief characteristics of the true Birds o f Paradise, and by this, together with its osteological structure,

exhibits its close affinity to the members of the genus Paradisea. In its habit of constructing a bower, in which

both sexes are accustomed to practise various evolutions for their amusement, we have a similarity of economy to the

typical Bower-birds, and one of such an unusual character as to make it o f paramount importance when looking for

the natural affinities of these birds. But the relationship o f the members of this subfamily to those of the Paradiseinæ

is further shown in the fact that, although the species of true Bower-birds composing the genus Chlamydodera do not

possess feathers upon the head of a like texture as is to be seen in Sericulus and Paradisea, yet some of them

exhibit in their brilliant nuchal crests, observable on the males, an affinity to another genus of Paradise-birds, that of

Dipkyllodes, which has, also only in the males, a similar adornment, but of a more exaggerated form. With regard

to the osteological structure o f the Bower-birds and true Birds of Paradise, Dr. Murie has been kind enough at my

request to make comparisons between the skeletons in the British Museum (of three species), with the following

results :-—

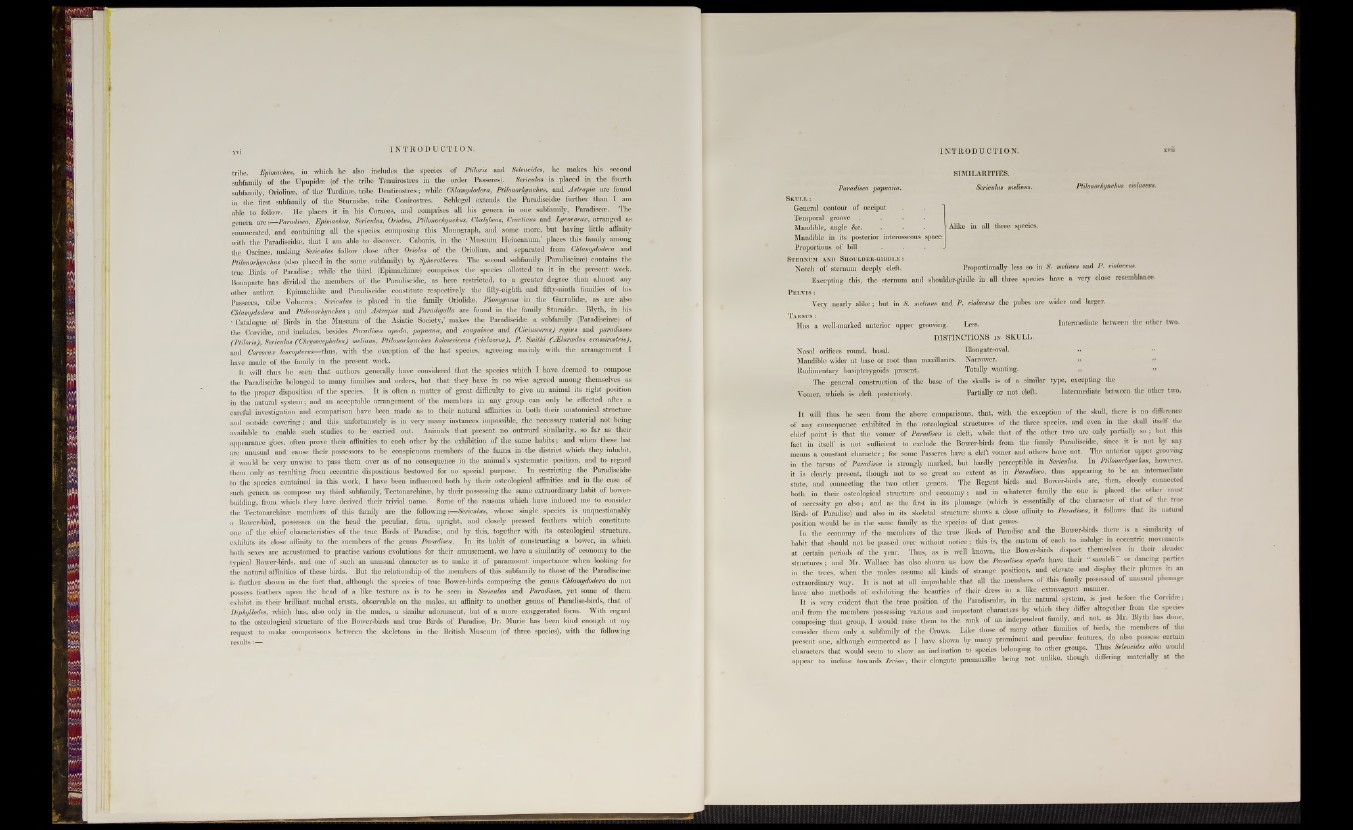

SIMILARITIES.

Paradisea papuana. Sericulus melinus. Ptilonorhynchus violaceus.

S k u l l :

General contour of occiput

Temporal groove . . . .

Mandible, angle &c. . . Alike in all three species.

Mandible in its posterior interosseous space

Proportions of bill . . -

S t e r n u m a n d S h o u l d e r -g ir d l e :

Notch of sternum deeply cleft. Proportionally less so in S. melinus and P. violaceus.

Excepting this, the sternum and shoulder-girdle in all three species have a very close resemblance.

P e l v i s :

Very nearly alike; but in S. melinus and P. violaceus the pubes are wider and larger.

T a r s u s :

Has a well-marked anterior upper grooving. Less. Intermediate between the other two.

DISTINCTIONS i n SKULL.

Nasal orifices roimd, basal. Elongate-oval. >»'

Mandible wider at base or root than maxillaries. Narrower. .

Rudimentary basipterygoids present. Totally wanting. „

The general construction of the base of the skulls is of a similar type, excepting the

Vomer, which is cleft posteriorly. Partially or not cleft. Intermediate between the other two.

It will thus be seen from the above comparisons, that, with the exception of the skull, there is no difference

of any consequence exhibited in the osteological structures of the three species, and even in the skull itself the

chief point is that the vomer of Paradisea is cleft, while that of the other two are only partially s o ; but this

fact in itself is not sufficient to exclude the Bower-birds from the family Paradiseidse, since it is not by any

means a constant character; for some Passeres have a cleft vomer and others have not. The anterior upper grooving

in the tarsus of Paradisea is strongly marked, but hardly perceptible in Sericulus. In Ptilonorhynchus, however,

it is clearly present, though not to so great an extent as in Paradisea, thus appearing to be an intermediate

state, and connecting the two other genera. The Regent birds and Bower-birds are, then, closely connected

both in their osteological structure and economy; and in whatever family the one is placed the other must

of necessity go also; and as the first in its plumage (which is essentially of the character of that of the true

Birds of Paradise) and also in its skeletal structure shows a close affinity to Paradisea, it follows that its natural

position would be in the same family as the species of that genus.

In the economy of the members of the true Birds of Paradise and the Bower-birds there is a similarity of

habit that should not be passed oyer without notice; this is, the custom of each to indulge in eccentric movements

at certain periods of the year. Thus, as is well known, the Bower-birds disport themselves in their slender

structures; and Mr. Wallace has also shown us how the Paradisea apoda have their “ sacaleli" or dancing parties

in the trees, when the males assume all kinds of strange positions, and elevate and display their plumes m an

extraordinary way. It is not at all improbable that all the members of this family possessed of unusual plumage

have also methods of exhibiting the beauties of their dress in a like extravagant manner.

It is very evident that the true portion of the Paradiseidse, in the natural system, is just before the Comdre;

and from the members possessing various and important characters by which they differ altogether from the species

composing that group, I would raise them to the rank of in independent femily, and not, as Mr. Blyth has done,

consider them only a subfamily of the Crows. Like , those of many other families of birds, the members of the

present one, although connected as I have shown by many prominent and peculiar features, do also possess certain

characters that would seem to show an inclination to species belonging to other groups. Thus Seleacidet a,»a would

appear to incline towards Preiser, their elongate prtcmaxilhe being not unlike, though differing materially at the