A -

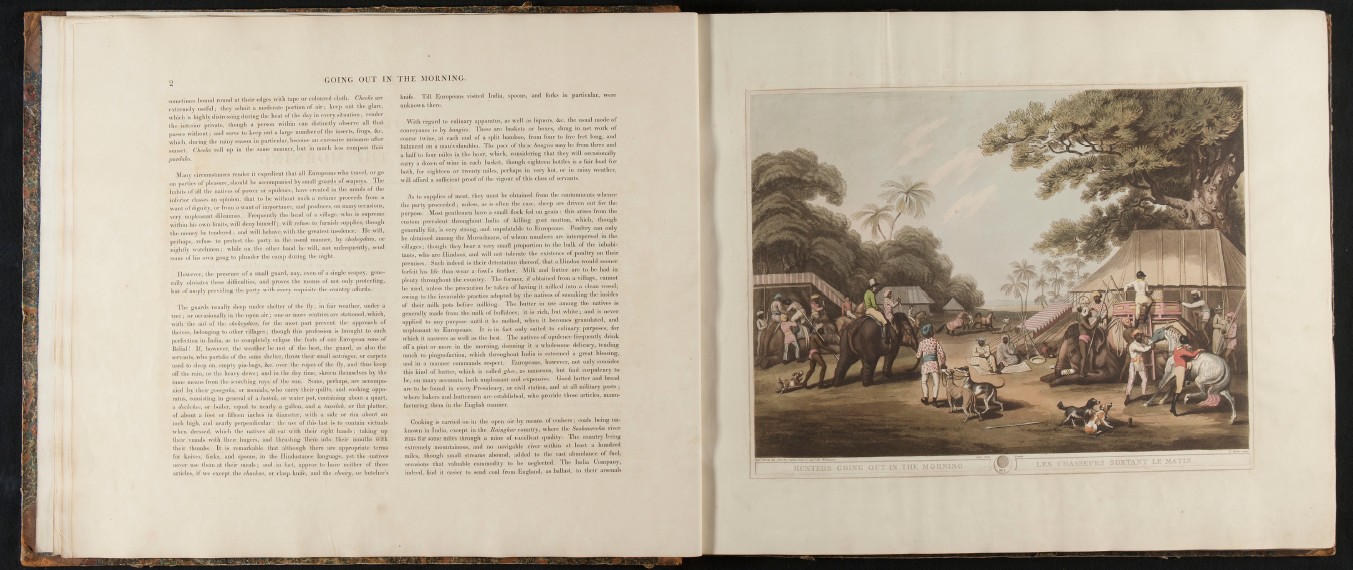

GOING OUT IN THE MORNING.

sonicliiiK-s boiiiul round al. tlicir edges wiüi tape or coloured cloLli. Chech are

(•\lrcmcly "»I'l'id ; lliey adiuil a inodcruLc porlioii of air; keep ouL the glare,

.vl.icl. is'liigldyd'islrcssing during Llie lieat. of I lie (lay in every situaLioii; render

iIk- inU-rlor p'rivuLe, though a ])erson within can disUnclly observe all tl.at

l)as:>es ^viUlo^ll; and servo to Ivccp o«l u large number of llic insects, Irogs, &c.

during the rainy season in particular, become an excessive nuisance after

sunsel. C/iech roll up in llie same manner, hut. in imicii less compass than

purdahs.

Many circunislances render il (•xpedient, tliat all Europeans who travel, or go

on parties of pleasure, should be accompanied l)y small guards of seapoys. The

Jiabits ol' all Ihe natives ol' power or opulence, have crealed in ihe minds of ihe

inferior classes an opinion, thai lo be •^^•ithouL such a retinue proceeds from a

want of dignily, or fnmi a want of imporlance, and produces, on many occasions,

very unpleasant dileuimas, Frecpiently the head of a village, who is supreme

within iiis ow u limits, will deny iiimself; will refuse lo furnish supi>lies, though

the money be tendered ; and will behave with the greatest insolence. He will,

])erhaps, reAise lo protect the i)art.y in the usual maimer, by chokcydars, or

ni'Hitlv walchmen ; while on ihc oilier haiul he will, not unfrequently, send

some of his o\vn gang lo plunder the camp din-ing the night.

However, the presence of a small guard, nay, even of a single seapoy, generally

obviales these dilliculties, and proves the means of not only protecting,

but of amply providing ihe parly with every recpiisile tlie country ailbrds.

The guar<ls usually sleep under shelter of the lly; in fair weather, under a

t r e e ; or occasionally in ihe open air; one or more cen tries are stationed, wliich,

u i l h ihe aid of ihe chokcijdorn, for the most part prevent the approach of

iheives, belonging lo other villages; ihongh this profession is brought lo such

perl'eclion in India, as lo completely eclij)se tin' feats of our European sons of

Belial! If, hoAvever, the weather be nol of tlie })cst, ihe guard, as also ihc

servants, who parlake of the same shelter, throw their small sairinges, or carpets

used to sleep on. empty pin-bags. See. over the ropes of the lly, and thus keep

oir the rain, or ihe heavy dews; and in the day time, skreen themselves by the

same means from the scorching rays of the sun. Some, perliaps, are accompanied

by their irowg'«^'''''. menials, who carry their ((uilts, and cooking apparatus,

consisting in general of a hotah, or water pot, containing about a (|uarl,

a dcckchcc, or boiler, ecpial lo nearly a gallon, and a tussilah, or üat plalter,

of about a foot or lifleen inches in dianieler, with a side or rim about an

inch high, and nearly ))erpendicular: the use of this last is to contain victuals

when dressed, which ihe nalivcs all eal with their right hands; taking np

iheir viands \\ilh iheir lingers, and ihrnsling ihem into their moutlis with

their thumbs. It is remarkable lhat although liiere are ap])ropriate terms

for knives, forks, and spoons, in the Ilindoslanec language, yet the -natives

never use them at ihcir meals; and in fact, appear lo have neither of those

articles, if we except the chuchoo, or clasp knife, and ihe choonj, or butcher's

knifc. Till Europeans visited India, spoons, and forks in parltcular, were

unknown therew

i t h regard to culinary apparatus, as well as liipu)i-s, &c. ihc usual mode of

conveyance is by bangks. These are baskets or boxes, slung in net work ol'

coai-se Iwine, al each end of a split bamboo, from four lo five feet long, and

balanced on a man's shoulder. Tlie pace of ihesc baiigies mixy he from ihrcc and

a half to four miles in ihe hoin-, which, considering thai they will occasionally

carry a dozen of wine in each biuskel, though eighteen bottles is a fair load for

both, for eighleen or twenty miles, perhaps in very hoi, or in rainy weallier,

w^ill allbrd a sufficient proof of ihe vigour of this class of servants.

As to supplies of meal, ihey must be obtained from the cantonments whence

the party proceeded; unless, as is often the ease, sheej) are driven out for the

purpose. Most genllemen have a small rtock fed on grain; this arises from the

custom prevalent throughout India of killing goal mutton, which, though

generally fat, is very strong, and unpalatable to Europeans. Poultry can only

b e obtained among llic Miissuliiiaiis, ol'wlioni luniiljcrs arc interspcr.sed in the

villages ; iboiigli ihey bear a very small proportion to the hnlk of Llie inhiibilanls,

who arc Hindoos, and will nol tolerate tlie existence of poultry on llleir

premises. Such indeed is their <leteslalion thereof, thai a Hindoo would sooner

fnrfcil his life llinn wear a fowl's fcallier. Milk and Inittcr are lo lie Imd in

pleuty ihroughoiit tlic country. The former, if obtained from a village, cannot

bo used, unless the precaution be lakcn of having it nidkc<l into a clean vessel;

owing to the invariable practice adopted by the natives of smoaking the insides

of their milk pols before milking. The butter in use among the natives is

generally made from the milk of bull'alocs; it is rich, but white ; and is never

applied to any purpose until it be melted, when it becomes granulated, and

unpleasant to Europeans. It is iii fact only suited to culinary purposes, for

which it answers as well ¡is the best. The natives of opulence frequently drink

o i l ' a pint or more in the morning, deeming it a wholesome delicacy, tending

much to |iinguefaetion, which throughout; India is esteemed a great blessing,

and in a maimer commands re.spoct. Europeans, however, not only consider

this kind of butter, which is callcd g/ice, as nauseous, bnt lind eorpulcncy to

be, on many accounts, both unlileasant and expensive. Good butter and bread

are to be found in every Presidency, or civil station, and at all military posts ;

where hakers and Imttcrmcii are established, who provide those articles, maimfacturing

them in the English manner.

Cooking is earricd on in the open air by means of embers; coals being unknown

in India, except in the Raing/mr country, where the Smbmmeka river

runs for some miles through a mine of excellent i|uality. The country being

extremely mountainous, and no navigable river within at least a hundred

miles, though small streams abound, added l,o the vast ahundanee of fuel,

occasions that valuable commoility to be iicglceted. Tile India Company,

indeed, find it easier lo send coal from England, as ballast, lo th(.ir ai.semds j j " Hl T í í T E H S