44

P L A T E XI.

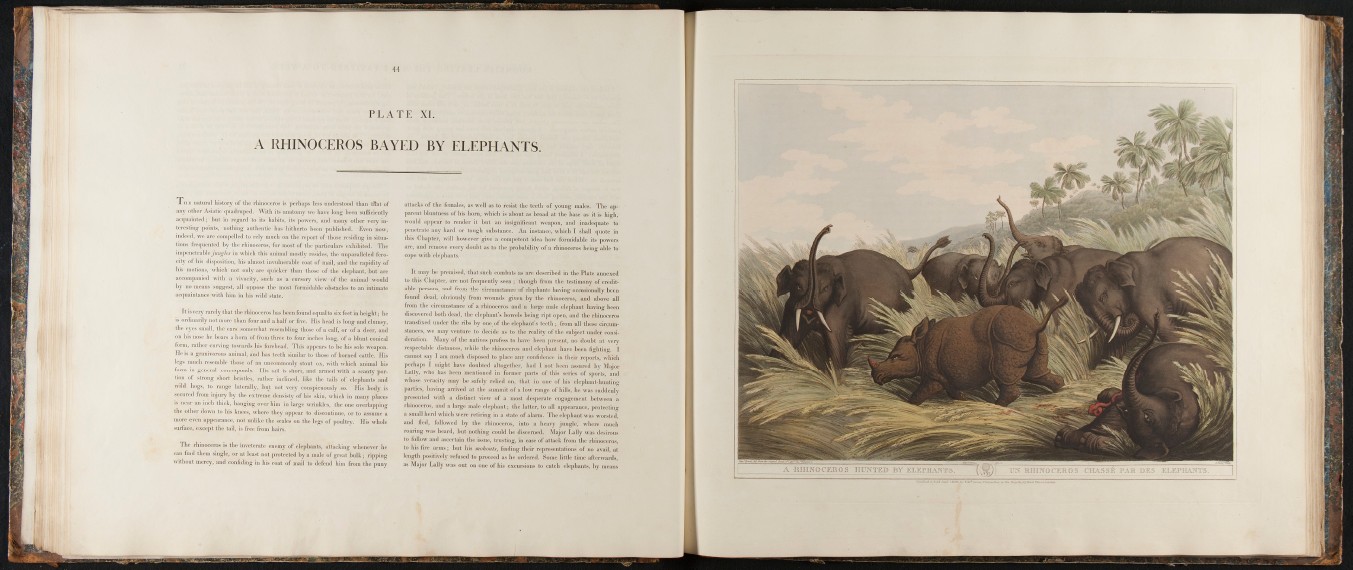

A RHINOCEROS BAYED BY ELEPHANTS.

THK iiuUirnl liislory of llic rhinoccros is perhaps less iiiulerstood llian lITat of

any other Asiatic quadruped, its aiialomy we have long been sufficiently

a('fiuainle<l; hul in regard lo its habits, its powers, and many other very in-

Icrosling points, noihing aulliontic has liillierto been published. Even now,

in(U'ed, wo are com |)e lied I o rely nnicli on Uie report of those residing in siUialions

fre<|uenled by the rhinoceros, for inosl of the partienlurs cxhibile<l. The

ini[>ciietral)le /«//o-Zw in Avliidi this animal mostly resides, the nnparalleled ferocity

of bis disposition, his almost invnlneruble coal of mail, and the rapidity of

Ills mo!ions, -vviiicli not only are quicker than those of llie elephant, but are

accompanied with a vivacity, such as a cursorj- view of ibe animal -would

by iio means suggest, all oppose the most formidable obstacles to an intimate

acquaintance with him in his wild stale.

ft is very rarely that tlie rhinoccros has been found equal to six feet i a height ; he

is ordinarily not more than four and a half or five. His head is long and clumsy,

the eyes small, llie ears somewhat rcseml)ling tho.se o f a calf, or of a deer, and

on Ins nose be boars u born of I'rom three to four inches long, o f a blunt conical

f.irm, rather ciirving towards bis forehead. This appears to be his sole weapon.

Me is a granivorous animal, and has teeth similar lo those of horned cattle. His

legs much resemble those of an uncommonly stout ox, with which animal his

iorm m general correspomls. His tail is .sborl, and armed with a scanty portion

of strong short bristles, rather inclined, like tlie tails of elephants and

M-ild hogs, to range laterally, but not very conspicuously so. His body is

secured from injury by the extreme densisty'of bis skin, which in many places

is near an inch thick, hanging over him in large wrinkles, tlie one overlapping

the other down to his knees, where tiiey appear to discontinue, or to assume a

more even appearance, not unlike the scales on the legs of poultry. His whole

surface, except tlie tail, is free from hairs.

The rhinoceros is the inveterate enemy of elephants, attacking whenever he

can find lljcm single, or at least not protected by a male of great bulk; ripping

without mercy, and confiding in his coat of mail lo defend him from the puny

attacks of the females, as well as to resist the teeth of young males. The a]>-

parcnl blinilness of his horn, which is about as broad at the base as it is iiigh,

would a|)pear to render it but an insignificant weapon, and inadequate to

penetrate any hard or tough substance. An instance, -wliicli 1 shall quote in

this Chapter, will however give a competent idea how formidable its powers

arc, and remove every doubt ;is lo the probability o f a rhinoceros being able to

cope witii ele])bants.

I t may be premised, that such combats as are described in the Plate annexed

lo this Cha])ter, arc not frequently .seen ; though from the testimony of creditable

persons, and from the circumstance of elephants having occasionally been

found dead, obviously from wounds given by the rhinoceros, and above all

from the circumstance of a rhinoceros and a large mate elephant having been

discovered both dead, tlie elephant's bowels being ript open, and the rhinoceros

transfixed under tlie ribs by one.of the elephant's teeth ; from all these circumstances,

we may venture lo decide as to the reality of the subject under consideration,

Many of the natives profess to have been present, no doubt at very

respectable distances, wliile the rhinoceros and elephani have been lighting. 1

cannot say I am much <lisposed to place any ronfidcnce in their reports, which

perhaps I might have doubted altogether, iiad 1 not been assured by Major

Lally, who has been mentioned in former parts of this series of sports, and

who.se veracity may be safely relied on, that in one of his elephanl-huntin"-

parties, having arrived at the summit o f a low range of bills, he was suddenly

presented with a distinct view of a most desperate engagement between a

rliinocero.s, and a large male ele|)hant; the latter, to all appearance, protecting

a small herd which were retiring in a stale of alarm. The elephant was worsted,

and lied, followed by the rhinoceros, into a heavy jiingle, where much

roaring was heard, but nothing could be discerned. Major Lally was desirous

to follow and ascertain the issue, trusting, in csise of attack from the rhinoceros,

to bis fire arms; but bis mokouts, finding their representations of no avail, at

length positively refused to proceed as lie ordered. Some little lime afterwards,

as Major Lally was out ou one of his excursions to catch elephants, by means

A -BHlMOCEROS^ J i ™ ™ MlMTfOCEBOS CIIASSÉ FAB BES XL^PIIAT^'S.

5. 1... E.h-ífimir.ITml—II«- u, lt¡. M.t],-llrá3JVmd Stt^n U.

'II

B i