picturesque than inviting, but at every step presents

some fresh study.

Passing one road on the right, to the Continental

Hotel and the kasbah, and another on the left, to the

beach, the chief mosque lies on the left, with

'•€ Interior.

the “ college” attached to it on the right;

into these none but Muslims can enter. Then begin the

notaries’ cells, and beyond the British and the Spanish

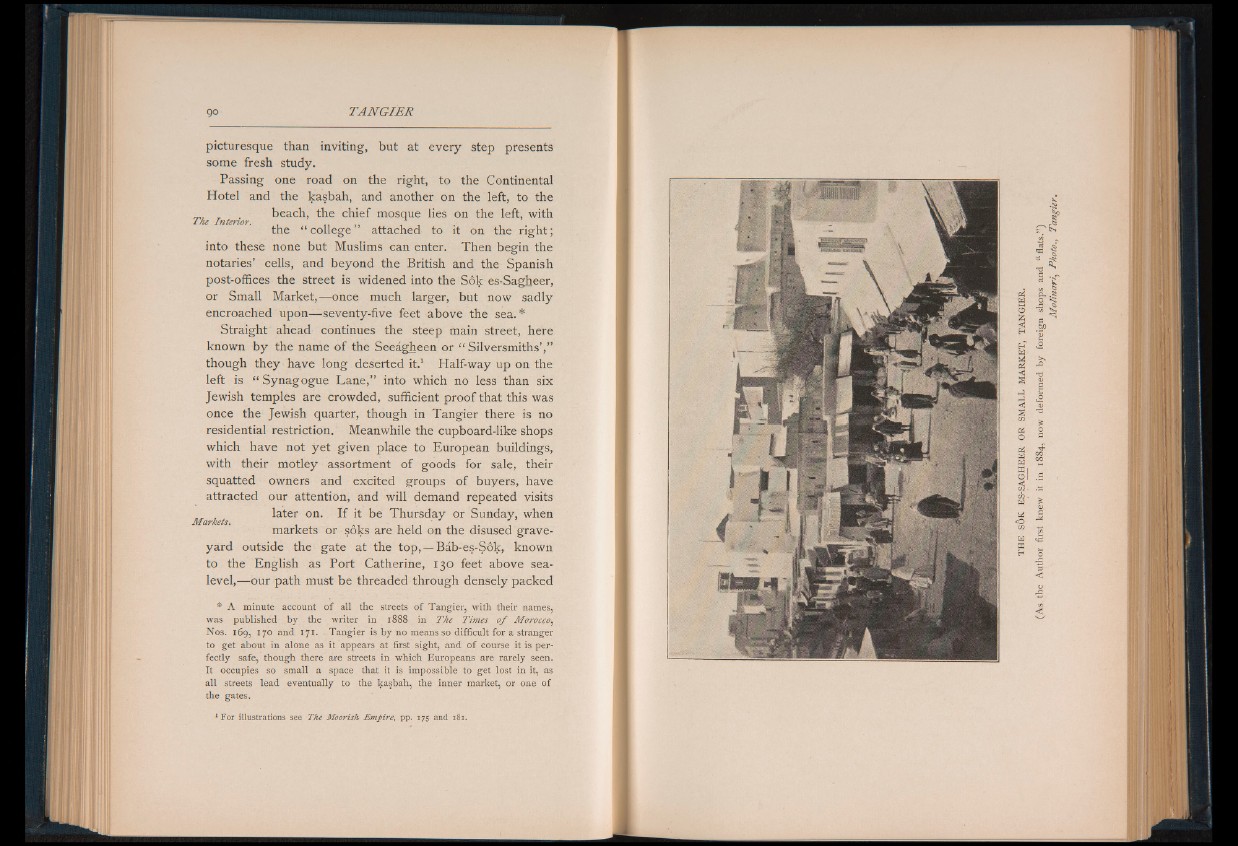

post-offices the street is widened into the Sok es-Sagheer,

or Small Market,— once much larger, but now sadly

encroached upon— seventy-five feet above the sea.*

Straight ahead continues the steep main street, here

known by the name o f the Seeagheen or “ Silversmiths’,”

though they have long deserted it.1 Half-way up on the

left is “ Synagogue Lane,” into which no less than six

Jewish temples are crowded, sufficient proof that this was

once the Jewish quarter, though in Tangier there is no

residential restriction. Meanwhile the cupboard-like shops

which have not yet given place to European buildings,

with their motley assortment of goods for sale, their

squatted owners and excited groups of buyers, have

attracted our attention, and will demand repeated visits

later on. I f it be Thursday or Sunday, when

arkets , *

markets or soks are held on the disused graveyard

outside the gate at the top, — Bab-es-Sok, known

to the English as Port Catherine, 130 feet above sea-

level,— our path must be threaded through densely packed

* A minute account of all the streets of Tangier, with their names,

was published by the writer in 1888 in The Times o f Morocco,

Nos. 169, 170 and 171. - Tangier is by no means so difficult for a stranger

to get about in alone as it appears at first sight, and of course it is perfectly

safe, though there are streets in which Europeans are rarely seen.

It occupies so small a space that it is impossible to get lost in it, as

all streets lead eventually to the kasbah, the inner market, or one of

the gates.