358 AN ATI DTE,

A NSEBES. A JVA TIDJi.

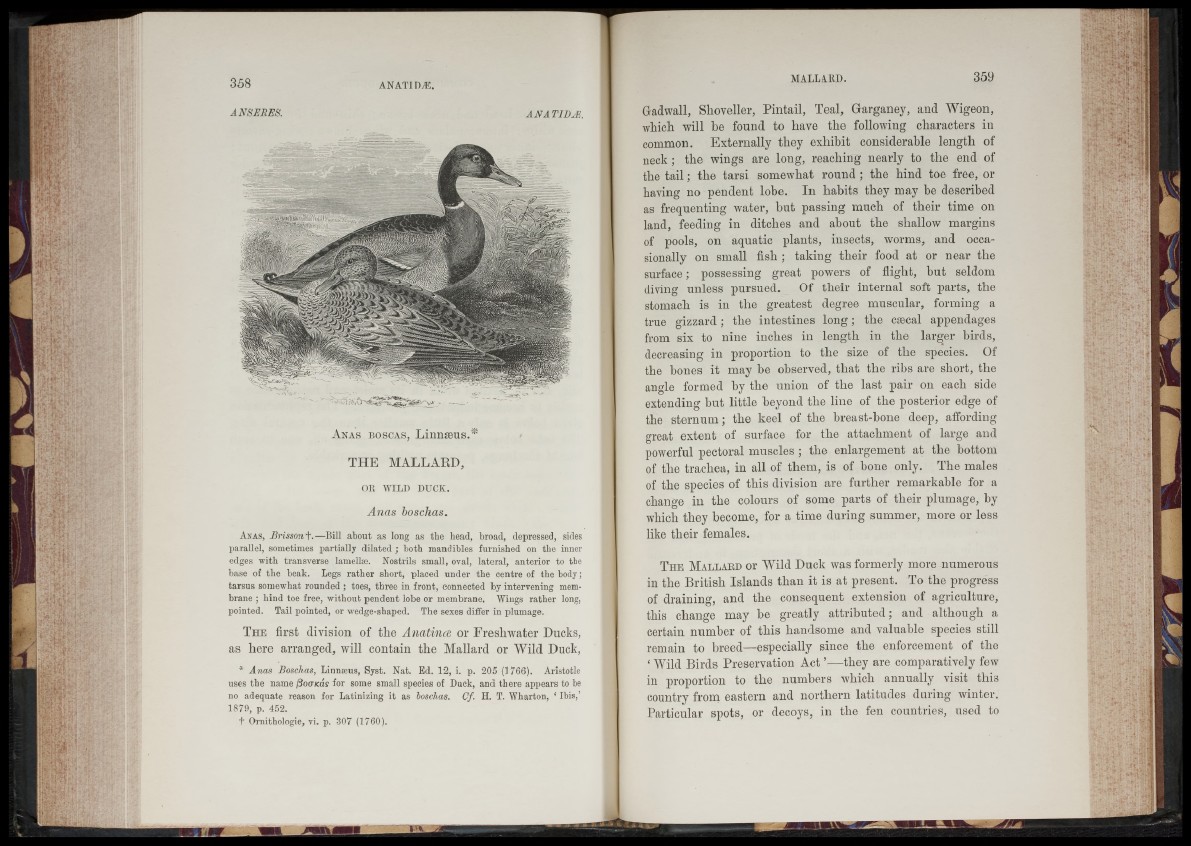

A n a s b o sc a s , Linnaeus.*

THE MALLARD,

OR WILD DUCK.

Anas boschas.

Anas, Brisson+.—Bill about as long as the head, broad, depressed, sides

parallel, sometimes partially dilated ; both mandibles furnished on the inner

edges with transverse lamellae. Nostrils small, oval, lateral, anterior to the

base of the beak. Legs rather short, placed under the centre of the body;

tarsus somewhat rounded ; toes, three in front, connected by intervening membrane

; hind toe free, without pendent lobe or membrane. Wings rather long,

pointed. Tail pointed, or wedge-shaped. The sexes differ in plumage.

The first division of the Anatince or Freshwater Ducks,

as here arranged, will contain the Mallard or Wild Duck,

* Anas Boschas, Linnaeus, Syst. Nat. Ed. 12, i. p. 205 (1766). Aristotle

uses the name ftoands for some small species of Duck, and there appears to be

no adequate reason for Latinizing it as boschas. Cf. H. T. Wharton, ‘ Ibis,’

1879, p. 452.

t Ornithologie, vi. p. 307 (1760).

Gadwall, Shoveller, Pintail, Teal, Garganey, and Wigeon,

which will be found to have the following characters in

common. Externally they exhibit considerable length of

neck ; the wings are long, reaching nearly to the end of

the tail; the tarsi somewhat round ; the hind toe free, or

having no pendent lobe. In habits they may be described

as frequenting water, but passing much of their time on

land, feeding in ditches and about the shallow margins

of pools, on aquatic plants, insects, worms, and occasionally

on small fish; taking their food at or near the

surface; possessing great powers of flight, but seldom

diving unless pursued. Of their internal soft parts, the

stomach is in the greatest degree muscular, forming a

true gizzard; the intestines long; the caecal appendages

from six to nine inches in length in the larger birds,

decreasing in proportion to the size of the species. Of

the bones it may be observed, that the ribs are short, the

angle formed by the union of the last pair on each side

extending but little beyond the line of the posterior edge of

the sternum; the keel of the breast-bone deep, affording

great extent of surface for the attachment of large and

powerful pectoral muscles ; the enlargement at the bottom

of the trachea, in all of them, is of bone only. The males

of the species of this division are further remarkable for a

change in the colours of some parts of their plumage, by

which they become, for a time during summer, more or less

like their females.

The Mallard or Wild Duck was formerly more numerous

in the British Islands than it is at present. To the progress

of draining, and the consequent extension of agriculture,

this change may be greatly attributed; and although a

certain number of this handsome and valuable species still

remain to breed—especially since the enforcement of the

‘ Wild Birds Preservation Act ’-—they are comparatively few

in proportion to the numbers which annually visit this

country from eastern and northern latitudes during winter.

Particular spots, or decoys, in the fen countries, used to