328 ANATIDÆ.

quite 300 Swans about the bay and backwater; and a good

many on the Exe (Zool. 1883, p. 452). A valuable account

of the Mute Swan on tlie rivers and broads of Norfolk has

been printed and privately distributed by Mr. H. Stevenson,

in anticipation of vol. iii. of bis ‘ Birds of Norfolk.’

Tlie adult bird lias the nail at the point of tlie beak, the

edge of the mandible on each side, the base, the lore, the

orifice of the nostrils and the tubercle, black; the rest of the

beak reddish-orange; the irides brown; the head, neck, and

all the plumage pure white; the legs, toes, and interdigital

membranes black.

The whole length of an old male is from four feet eight

inches to five feet; the weight about thirty pounds ; the black

tubercle at the base of the beak is larger than in the female;

the neck is thicker, and the bird swims higher out of the

water. The body of the female is smaller, the neck more

slender, and she appears to swim deeper in the water. This

latter point is referable to a well-known anatomical law, that

females have less capacious lungs than males, and her body

therefore is less buoyant. Marked Swans have been known

to live fifty years.

The young Mute Swan, in July, has plumage of a dark

bluisli-grey, almost a sooty-grey ; the neck, and the under

surface of the body rather lighter in colour ; the beak lead-

colour ; the nostrils and the basal marginal line black. The

same birds, at the end of October, have the beak of a light

slate-grey, tinged with green ; the irides dark; head, neck,

and all the upper surface of the body, nearly uniform sooty-

greyish brown; the under surface also uniform, but of a

lighter shade of greyish-brown. Young birds at the end

of October are nearly as large as the old birds. After the

second autumn moult but little of the grey plumage remains;

when two years old they are quite white; and breed in their

third year.

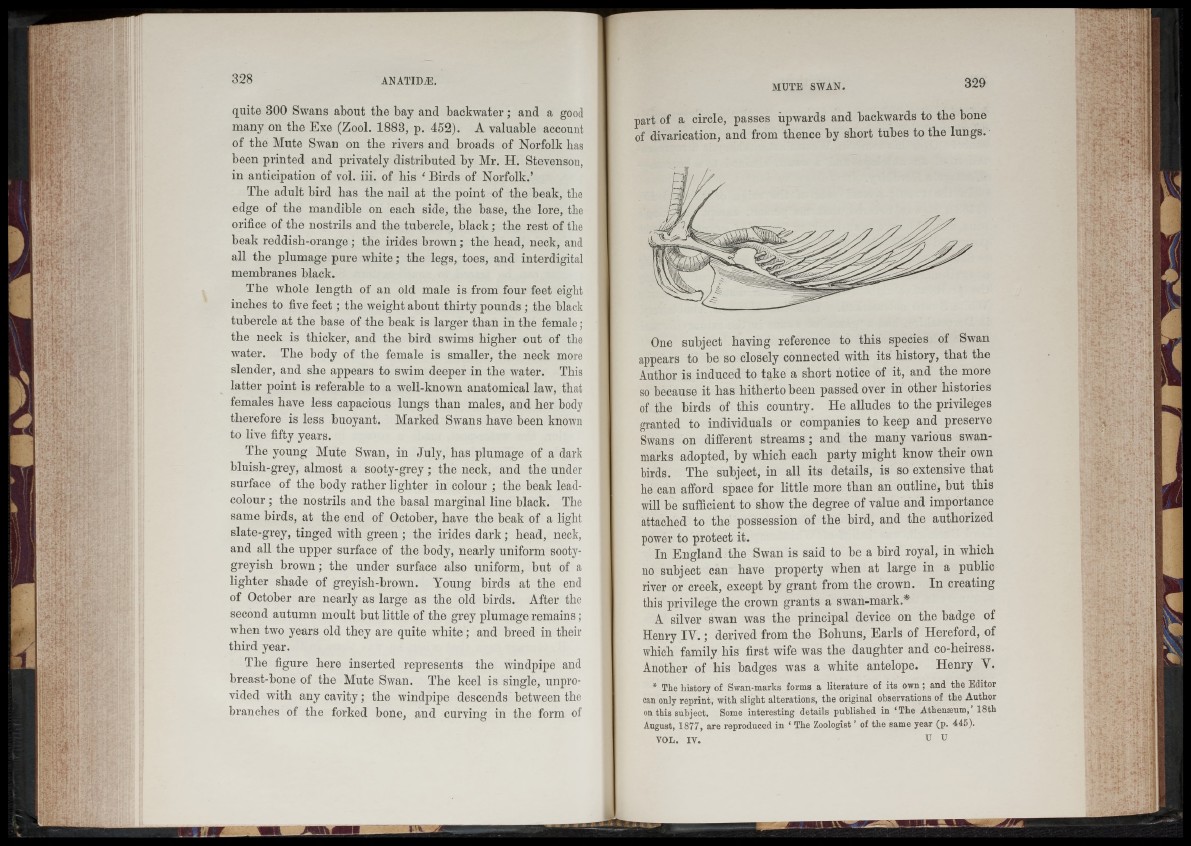

The figure here inserted represents the windpipe and

breast-bone of the Mute Swan. The keel is single, unprovided

with any cavity; the windpipe descends between the

branches of the forked bone, and curving in the form of

MUTE SWAN. 329

part of a circle, passes upwards and backwards to the bone

of divarication, and from thence by short tubes to the lungs.

One subject having reference to this species of Swan

appears to be so closely connected with its history, that the

Author is induced to take a short notice of it, and the more

so because it has hitherto been passed over in other histories

of the birds of this country. He alludes to the privileges

granted to individuals or companies to keep and preserve

Swans on different streams ; and the many various swan-

marks adopted, by which each party might know their own

birds. The subject, in all its details, is so extensive that

he can afford space for little more than an outline, but this

will be sufficient to show the degree of value and importance

attached to the possession of the bird, and the authorized

power to protect it.

In England the Swan is said to be a bird royal, in which

no subject can have property when at large in a public

river or creek, except by grant from the crown. In creating

this privilege the crown grants a swan-mark.*

A silver swan was the principal device on the badge of

Henry IY .; derived from the Bohuns, Earls of Hereford, of

which family his first wife was the daughter and co-heiress.

Another of his badges was a white antelope. Henry Y.

* The h istory of Swan-marks forms a lite ra tu re of its ow n ; an d th e Ed ito r

can only re p r in t, w ith slig h t a lte ra tio n s, th e original observations of th e Au th o r

on th is su b je ct. Some in te re stin g d e ta ils p u b lish ed in ‘The Athenaeum, 1 8 th

August, 1877, a re reproduced in ‘ The Zoologist ’ of th e same y ear (p. 445).

VOL. IV. u u