LONG- E A R E D OW L.

OTUS VULGARIS.

Tills species is ley no MMH uncommon in mod parts of Great Itritaiu. I never yet observed a ]j»m;-cap*d

Owl on the barren moors or treeless deer-forests of Sutherland and Caithness, or on the Outer Islauds j but

with these exceptions I have found it generally distributed over almost every eountf 1 have visited. It np|>cars

most numerous in those localities where tir-plant at ions of moderate si/e are to he met with. I particularly

remarked in several districts in the Highlands, where the hill-sides for miles are covered by dense forests of

Scotch fir or larch, that not a single specimen was either seen or heard.

The Long-eared Owl is strictly nocturnal in its habits, seldom venturing far from its haunts till twilight

has set in. During the day it rests in some thick fir in the densest, part of the wood it frequents. 1 noticed

that, when these birds have young to provide for, they commence to move about from tree to Iris; some time

before the sun has disappeared. An excited mob of Blackbirds and Thrushes oeeas Ion ally collects, and, with

angry screams, persistently follows the hated Intrude* every time it shifts ils position.

Small birds and mice are the usual prey of this species. When living in Dast Lothian, I used to observe

those Owls during the summer coming regularly at dusk to the stack-yard for rats or mice, though the woods

where they nested were HI a distance of nearly two miles. I have repeatedly seen them parched on the stacks

or fai-m-implements, intently watching for the slightest rustle among the straw, when they would instantly

glide to the spot. Unfledged nestlings n.re also taken. I noticed a Long-eared Owl making several visits one

evening to a Iwat-shed on one of the broads in Norfolk; and on examining the place the next morning I

discovered that a brood of young Swallows bad disappeared during the night. I do not think that the most

ardent game-preserver could make the slightest complaint against this species.

Tho young birds have a peculiarly sad and plaintive whistle (something resembling a deep-drawn sigh)

when calling for their food. lVhen there are several broods in the same plantation, the effect of their wailing

erics is any thing hut lively when listened to ou a still night in the gloomy depths of the pine-woods, their

mournful notes breaking out first on one side, then nn another, and finally being answered from all quarters

at once.

The Loug-earcd Owl is by no means fastidious when choosing a cradle in which to rear its family. A

mass of dead leaves and twigs that have lodged in a cleft among the branches, the old dray of a squirrel, or

the deserted nest of a Crow appears equally suited to its nspiiroments. I have never met with an instance

where there was evidence that the laid had been its own architect; indeed, I believe this Owl will not make

even t h e slightest additions or repairs to the collection of rubbish or the antiquated structure it selects.

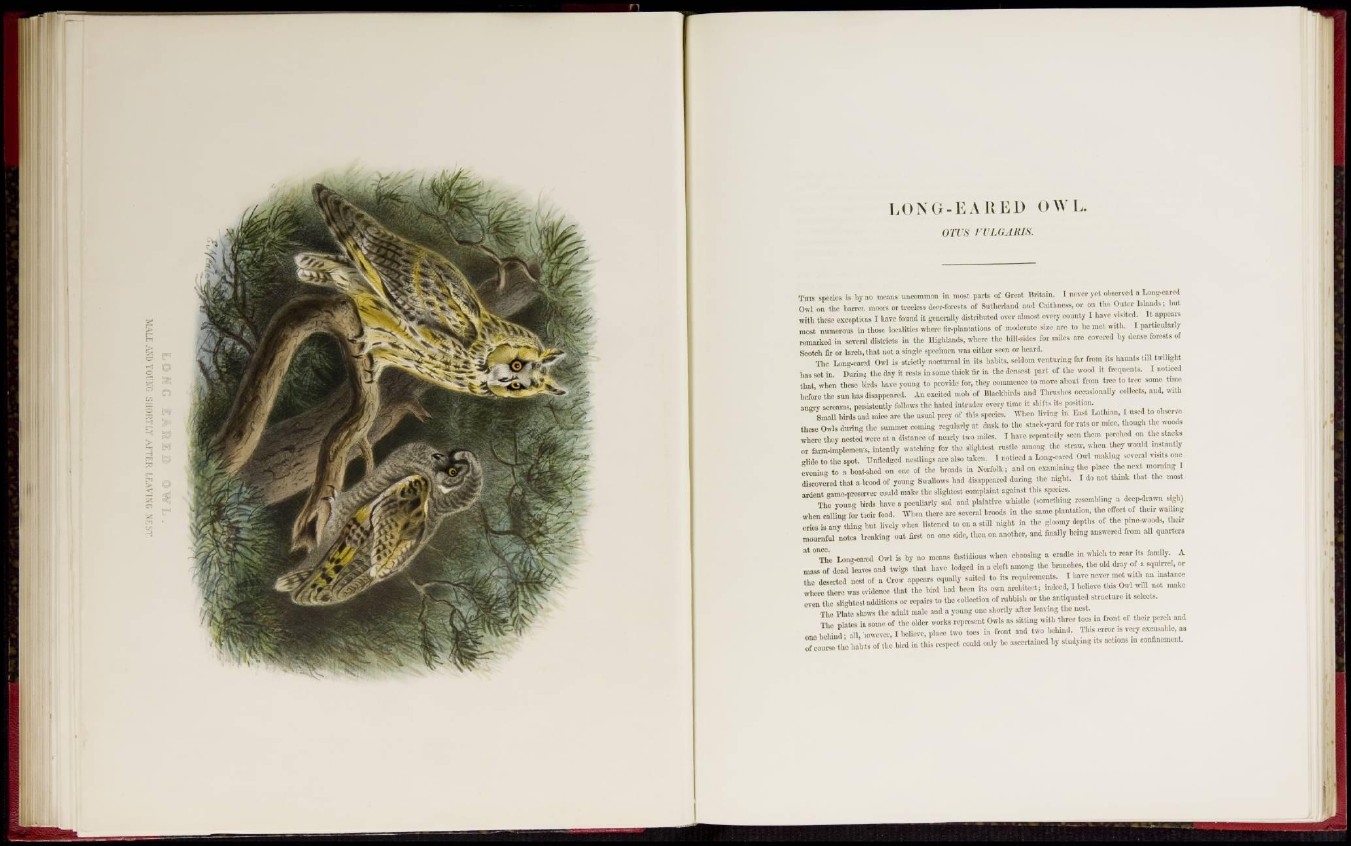

The Plate shows the adult male and a young one shortly after leaving the nest.

The plates in some of the older works represeut Owls as silling with three toes in front of their perch and

one behind; all, however, l believe, place two toes in front and two behind. This error is very excusable, as

of course Hie habits of the bird in this respect could only be ascertained by studying ils actions hi confinement.