NUMIDA MELE 3yIS

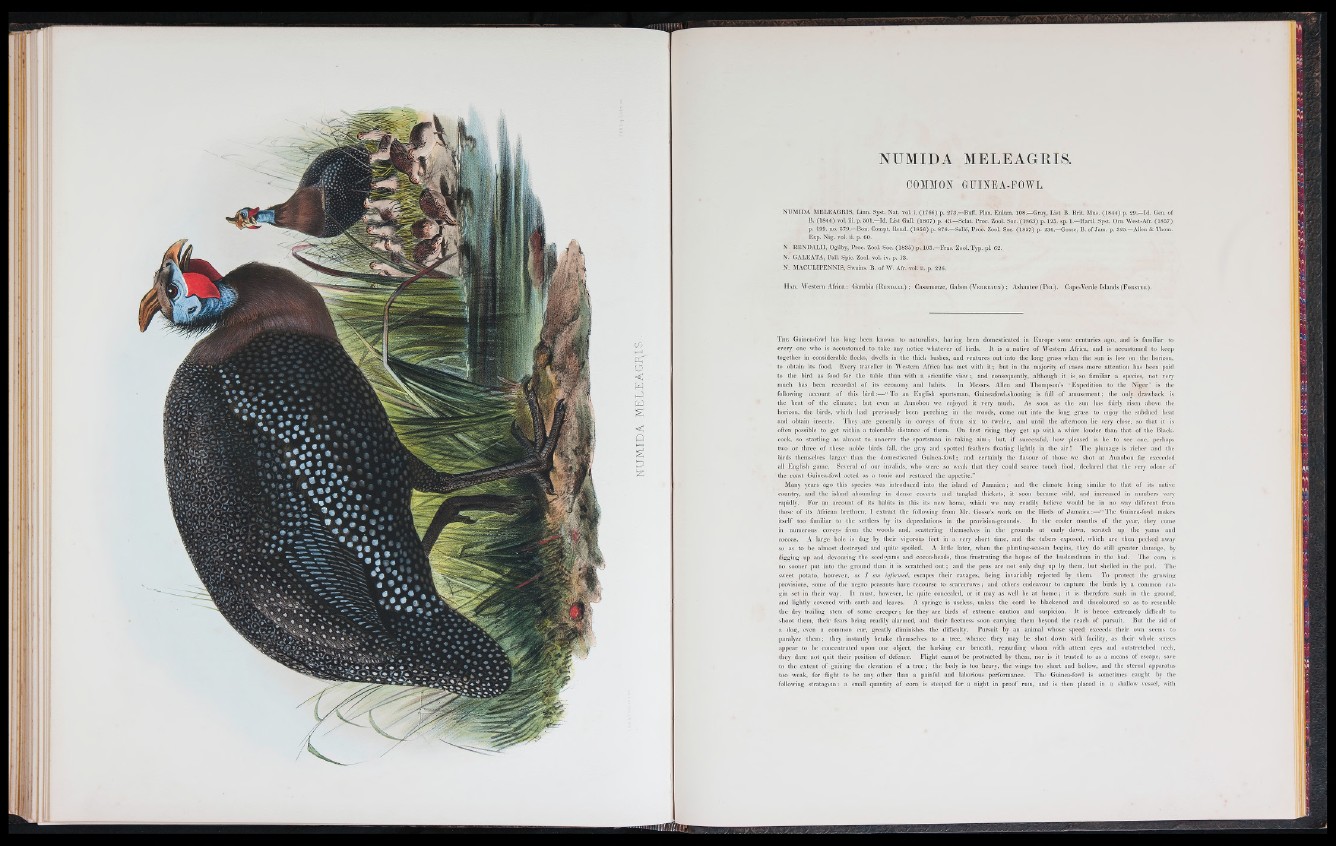

NUMIDA ME L E AG RI S.

I &OMMON G:U:INEÄ-;FOWE,

NUMIDA MELEAGRIS, Linn. Syst. Nat. vol. i. (1766) p. 273.—Buff. Plan. Enlum. 1jÖ8.—Gray, List B. Brit. Mus. (1844) p. 29.—Id. Gen. of

• B, (1844) vol. iii. p; 501.-—Id. List Gall. (1867). p. 43.TrrSclat. Proc. Zool. Soc. (1863) p. 125. sp. 1-—Hartl. Syst. Orn. West-Afr. (1857)

p. 199. no. 579—Bon. Compt. Rend. (1856).p. 876.—Sallé, Prój& Zooli. Soc. (1857) p. 236—Gosse, B. of Jam. p. 325.—Allen & Thom.

Exp. Nig] vol. ii. p. 60.

N. RÉNDALÍI, Ogilby, Proc. ZftgkSoc.. (1835,) p.. 103.—Fras. ZooL.Typ. pL 62.

N. GALEATA, Pall. Spic. Zool. vol. iv. p. 13.

N.. MAGULIPENNISy Swains. B. of W. Afr. wdí^i&p.’.? 226.

H ab . Western Africa: Gambia ( R en d a l l ) ; Casamanze, G a b o n (V E R R EA U x ) ; Ashantee ( P e l ) . Cape-Verde Islands ( F or s t er ) .

T h e Guinea-fowl has long been known to naturalists, having been domesticated in Europe , some centuries ago, and is familiar to

every one who is accustomed to take any notice whatever of .birds. It is a native o f ¡Western Africa, and is a c c u s tom e d to keep,

together in considerable flocks, dwells iii. the thick hushes, and ventures, out, into the. long grass when .the. sun is low on the . horizon,

to obtain its food. Every traveller in Western Africa has met with i t; hut in thé majority, of cases mqre attention .lias been paid

to the bird as food for the table than with a scientific view and eonsequçntly, ' although i t . is. so. familiar a species, not very

much has been recorded of its • economy and habits. In Messrs. Allen and Thompson’s ‘ Expedition to the Niger ’ is the

following account of this bird To an English sportsman, Guineafowlrshooting, is ’ full o f amusement ; the only' drawback is

the heat o f the climate; but even a t Aunobou we enjoyed-, it very much. As soon as the sun has fairly risen above the

horizon, the birds, which ;had previously been perching in the woods, come out into the long grass to enjoy the subdued heat

and. o b ta in insects. T h e y \a re generally in coveys of from six to twelve,, and until the afternoon lie very close, so that it is

often possible to g et within a tolerable distance of them. On first rising they get up with a whirr louder than that of the Blackcock,

so startling as almost to unnerve the sportsman in ta k in g a im ; b u t , if successful, how pleased is he to see one, perhaps

two or three of these noble birds fall, the gray and spotted feathers floatiug lightly in the air !£ ■;The plumage is richer and the

birds themselves larger than the domesticated Guinea-fowl ; and certainly the flavour of those we Mhot a t : Aunobou far; exceeded

all English game. Several o f our invalids, who were .so weak that they could scarce touch food, declared that the very odour of

the roast Guinea-fowl acted as a tonic and restored thé appetite.”

Many years ago this species was introduced into the island of Jamaica; and the climate being similar to that of its native

country, and the island abounding in dense coverts and; tangled thickets, it ' soon became wild, and. increased in numbers very

rapidly. For an account of its habits in .this its new home, which we may readily believe would be in no way different from

those of its African brethren, I extract the following from Mr. Gosse’s work on the Birds of Jamaica:—“ The Guinea-fowl makes

itself too familiar to the settlers by its depredations in the provision-grounds. In the cooler months of the year, they come

in numerous coveys from the woods and, scattering themselves in the grounds a t ’ early dawn, scratch up- the yams and

cocoas. A large hole is dug : by their vigorous feet in a very short time, and the tubers exposed, which a r e . then' pecked away

so as to , be almost destroyed and quite spoiled. A little later, when the planting-season begins, they do still greater damage, by

digging up and devouring the seed-yams and cocoa-heads, thus frustrating the hopes of. the husbandman in the bud. The corn is

no sooner put into the ground than it is scratched quj|; and the peas are not only dug up by them, but shelled in the pod. The

sweet potato, however, as I am informed, escapes their ravages, being invariably rejected by . them. To protect the growing

provisions, some of the negro peasants have recourse to scarecrows; and others endeavour to capture the birds by a common rat-

gin set in their way. It must, however, be quite concealed, or it may as well be at home ; it is therefore sunk in the ground,

and lightly covered with earth and leaves. A springe is useless, unless the - cord be blackened and discoloured so as to resemble

the dry trailing stem of some creeper; for they are birds of extreme .caution and suspicion. It is hence extremely difficult to

shoot them, their fears being readily alarmed, and their fleetness soon carrying them beyond the reach o f pursuit. But the aid of

a dog, even a common cur, greatly diminishes the difficulty. . Pursuit By an animal whose speed exceeds their own seems to

paralyze them ; they instantly betake themselves ' to a 't r e e , whence they may be shot down with facility, as their whole senses

appear to be concentrated upon one object, the barking cur beneath, regarding whom with attent eyes and outstretched neck,

they dare not quit their position of defence. Flight cannot be protracted by them, nor is it trusted to as a means o f escape, save

to the extent of gaining the elevation of a tree ; the body is too] heavy, the wings too. short and hollow, and the sternal apparatus

too weak, for flight to be any other than a painful and laborious performance. The Guinea-fowl is sometimes caught by the

following stratagem: a small quantity of corn is steeped for a night in proof rum, and is then placed in. a shallow vessel, with