EU PLO CAjy\TT S "_Z«1E LAN OTIS

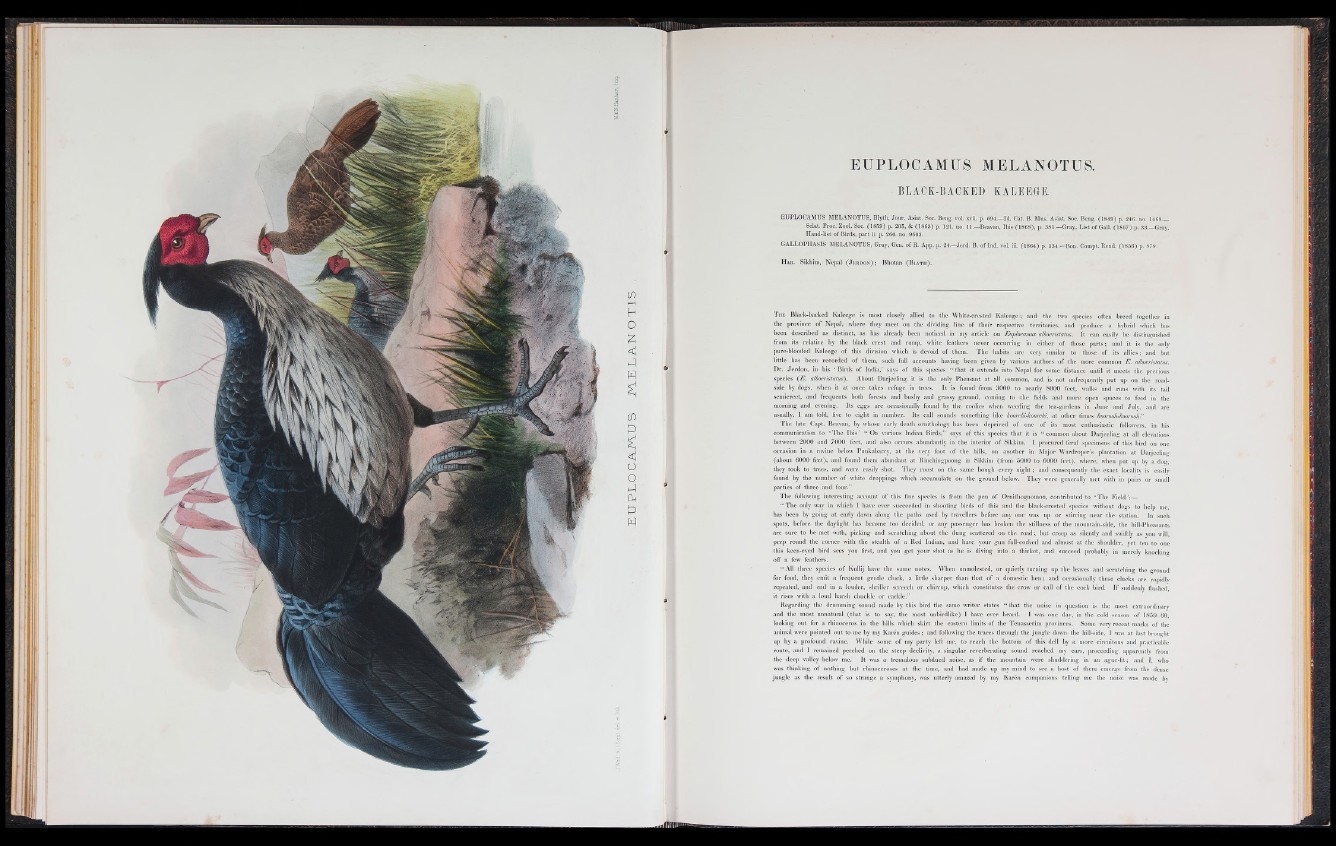

EUPLOCAMUS MELANOTUS.

BLACK-BACK KI) KALEEGE.

EUPLOCAMUS MELANOTUS, Blyth, Jour. Asiat. Soc. Beng. voi/ xvii. p. 694.—Idi Cat. B. Mus. Asiat. Soc. Beug. (1849) p. 246. noi 1469__

Sclat. Proc. ZoiilpSoc. (1859) p. 205, &;(1863) p. 121;' Hò. l i .—Béavàn, IbisJ(l'8'68), p.‘381.—Gray, List of Gail. (1867) p. 33:—Gray,

Hand-list of Birds, part iii p. 260. no. 960.3;'

GALLOPHASIS MELANOTUS, Gray, Gen. óf B. App. pi 24.—Jerd. B. of Ind. vol. iiii‘^1864) p. 534—Bon. Compt. Rend. (1856) p. 879.

H ab. Sikhim, Nepal^(jERDON) ; Bkotan (B ly th ) .

T h e Black-backed Kaleege is most closely allied to the White-crested Kaleege; and the two species often breed together in

the province of: Nepal, where they meet on the* dividing lineNof their respective .^territories, and «produce a hybrid which has

been described as distinct, as .has already been noticed in .my article • on 1 Euplocamus albocristatw. It can easily be distinguished

from its relative by the black crest and rump, white feathers never occurring in either of those p a rts ; and it is the only

pure-blooded Kaleege of this division which is devoid of them. The habits are very similar to those of its allies; and but

little?-has been recorded of them, such full accounts having been given by vario.us authors ofi the more common E . albocristatus.

Dr. Jerdon, in his ‘ Birds of India,’ says of this species “ that it extends into Nepal for some'distance until it meets the previous

species (E . albowistatusW&AbovX Darjeeling it is the only Pheasant a t all common, and is not unfrequently put up on the roadside

by dogs, when it a t once takes refuge in trees. It is found from 3000 to nearly 8000 feet, walks and runs with its tail

semierect, and frequents both forests and bushy and grassy ground, coming to the fields., and more • open spaces to feed in the

morning and evening. Its eggs, are occasionally found by the coolies when weeding the teargardens in June and July, and are

usually, I am told, five to eight in number. Its Call sounds something like koorchi-koorcln, a t other times koorooh-Icoorooh.”

The late Capt. Beavan, by whose early death ornithology has been deprived of one 0 its mosf «yffiiiusiastic followers, in his

communication to ‘The Ib is ’ “ On various Indian Birds,” says of this species that it is “ common about Daijeeling a t all elevations

between 2000 and 7000 feet, and also occurs abundantly in the interior of Sikkim. I procured feral specimens of this bird on one

occasion in a ravine below Punkabarry, a t the very foot of the hills, on another in Major Wardroper’s plantation at Darjeeling

(about 6000 feet), and found them abundant at Bincbingpoong in Sikkim (from 5000 to 6000 feet), where, when put up by a dog,

they took to trees, and were easily shot. They roost on the same bough every n ig h t; and consequently the exact locality is easily

found by the number of white droppings which accumulafe on the ground below. They were generally met with in pairs or small -

parties of three and four.”

The following interesting account of this fine species is from the pen of Ornithognomon; .contributed to ‘The Field’:—

“ The only way in which I have ever succeeded in shooting birds of this and the black-crested species without dogs to help me,

has been by going a t early dawn along file paths used by travellers before any; one was up stirring near the station. In such

spots, before the daylight has become too decided, or any passenger has broken the stillness o f the mountain-side, the hill-Pheasants

are sure to be met with, picking and scratching about the dung scattered on the ro a d ; but creep as silently and swiftly as you will,

peep round the corner with the stealth of a Red Indian, and have your gun full-cocked and almost a t the shoulder, yet ten to one

this keen-eyed bird sees you first, and you get your shot as he is diving into a thicket, and succeed probably in merely knocking

off a few feathers.

“ All three species of Kullij have the same notes. When unmolested, or quietly turning up the leaves and scratching the ground

for food, they emit a frequent gentle cluck, a little sharper than that o f a domestic lien ; and occasionally these clucks are rapidly

repeated, and end in a louder, shriller screech orM n irrup. which constitutes the crow or call of the cock bird. If suddenly flushed,

it rises with a loud harsh chuckle or cackle.”

Regarding the drumming sound made by this bird the same writer states “ that the noise in question is the most extraordinary

and the most unnatural (th a t is to say, the most unbirdlike) I have ever heard. I was one day, in the cold season of 1859-60

looking out for a rhinoceros, in the hills, which skirt the eastern limits o f the Tenasserim provinces. Some very recent marks of the

animal were pointed out to me by my Karen guides; and following the traces through the jungle down the hill-side, I was a t last brought

up by a profound ravine. While some of my party left me, to reach the bottom of this dell 'b y a more circuitous and practicable

route, and I remained perched on the steep declivity, a singular reverberating sound reached my ears, proceeding apparently from

the deep valley below me. It was a tremulous subdued noise, as if the mountain were shuddering in an ague-fit; and I, who

was thinking of nothing but rhinoceroses at the timej and had made up my mind to see a host of them emerge from the dense

jungle as the result of so strange a symphony, was utterly amazed by my Karen companions telling me the noise was made by