In d ian Mosque-Swallow.

Himndo ergthropygia, Sykes, Proc. of Comm, of Scl. and Corr. of Zool. Soc„ part u. 1832, p. 8 3 ,-J e rd . Madr.

Joum. Lit. and Sci., vol. xi. p. 237 Blyth, Ibis, 1866, p. 337.

Nipalensis, Hodgs. Journ. Asiat. Soc. Beng., vol. v. p. 780.

Damien, Blyth, Cat. of Birds in Mus. Asiat. Soc. Calc., p. 198—Jerd. Birds of Ind., vol. i. p. 100.—

Horsf. and Moore, Cat. of Birds in Mus. East-India Comp., vol. i. p. 92.

Masjid Ababil, of the Hindoos, i. e. Mosque-Swallow.

A ll the remarks respecting Indian Mosque-Swallovvs that have from time to time appeared in various

scientific periodicals, have reference to this species, originally characterized by Col. Sykes, and

differing from its western and eastern allies, Cecropis nifula and C. Daurico, with which it has often been

confounded, in its smaller size, and in the striae on the breast being intermediate, or not so apparent as

in the one nor so faint as in the other—characters by which the bird may be at once distinguished, and

which tend to confirm the opinion of those ornithologists who regard it as a distinct species. However

narrowly defined may be the range of the other members of the genus Cecropis, that of the present bird

appears to be a very wide one; for it is said to frequent the whole of India, from the most southern

part of the peninsula to the Himalayas, and is, moreover, seen in such countless numbers as to excite

the utmost astonishment. Col. Sykes relates that it “ appeared in millions in two successive years in the

month of March, on the parade-ground at Poona; but they rested a day or two only, and were never seen

in the same numbers afterwards.” It seems to differ but little in habits and nidification, or in the similarity

of the colouring of the sexes, from its immediate congeners. Dr. Jerdon does not say if it be or be not

a migrant; in all probability it merely changes from one district to another at opposite seasons, without

leaving the country, its movements being influenced by the nature of the season. Mr. Hodgson states that

it “ is the Common Swallow of the central region of Nepal, a household creature, remaining for seven or

eight months of the year;” while Dr. Jerdon informs us that he has seen it nesting in Southern India.

In Horsfield and Moore’s ‘ Catalogue of the Birds in the Museum of the East-India Company,’ there is a

note (from whose pen is not stated) which I take the liberty of transcribing :—

“ This Swallow in general prefers the proximity of jungles. I observed it in those round the Neilgherries

(and also on the summit of the hills), in various other parts of the west coast, and in the Carnatic, at the

Tapoor pass. In the northern parts of the tableland, however, I have seen it occasionally in the cold

weather only, both in the neighbourhood of water and on dry open plains. In the jungles it frequents, it is

often seen seated in great numbers on a tree.”

In Dr. Jerdon’s ‘ Birds of India,’ it is stated that “ This Swallow is found all over India, rarely extending

to Ceylon; but it is more common in hilly or jungly districts than in the open plains. I have seen them

in every part of India, from the extreme south to Darjeeling. A few couples, at all events, breed in the

South of India; for I have seen their nests on a rock at the Dimhutty waterfall on the Neilgherries, twenty

or thirty together. I have found one or two nests in deserted out-houses in Mysore; and they are said to

breed very constantly on large buildings, old mosques, pagodas, and such like; hence the native name of

Mosque-Swallow, in the South of India; but I rather think there is a considerable increase of their numbers

during the cold weather; and it was, no doubt, at the period of their northward migration that Col. Sykes

saw them in such vast numbers at Poona. From Hodgson’s remarks I conclude that they breed in Nepaul;

and Adams says that they breed in the North-west Himalayas, migrating in winter to the Punjab. It

constructs a spherical or oval-shaped mud nest, with a long neck or tubular entrance, of the kind which is

called a retort nest; and the eggs are white, faintly marked with rusty-coloured spots. The bird may often

be seen seated on trees in great numbers. Mr. Elliot says (taking, I imagine, a native idea), “ It flies after

insects, and, when its mouth is full, sits on a tree to devour them.”

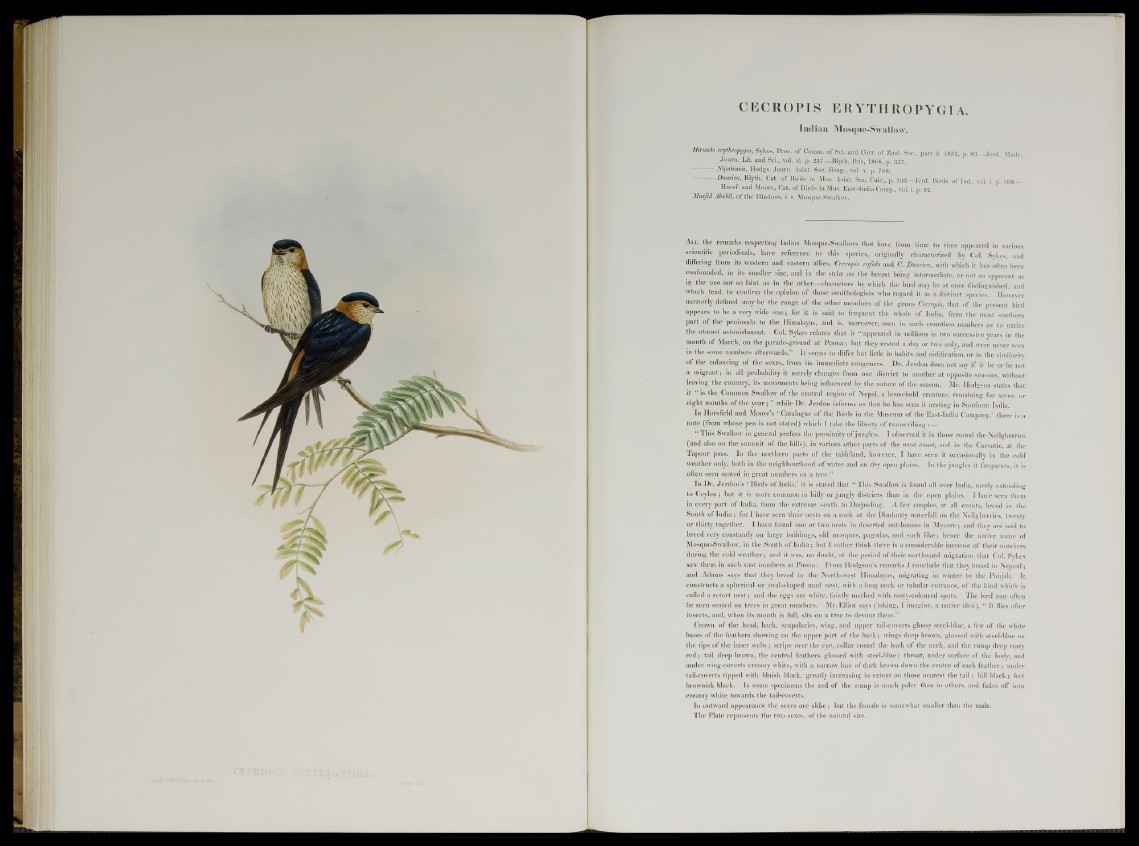

Crown of the head, back, scapularies, wing, and upper tail-coverts glossy steel-blue, a few of the white

bases of the feathers showing on the upper part of the back; wings deep brown, glossed with steel-blue on

the tips of the inner webs; stripe over the eye, collar round the back of the neck, and the rump deep rusty

red; tail deep brown, the central feathers glossed with steel-blue; throat, under surface of the body, and

under wing-coverts creamy white, with a narrow line of dark brown down the centre of each feather; under

tail-coverts tipped with bluish black, greatly increasing in extent on those nearest the tail; bill black; feet

brownish black. In some specimens the red of the rump is much paler than in others, and fades off into

creamy white towards the tail-coverts.

In outward appearance the sexes are alike; but the female is somewhat smaller than the male.

The Plate represents the two sexes, of the natural size.