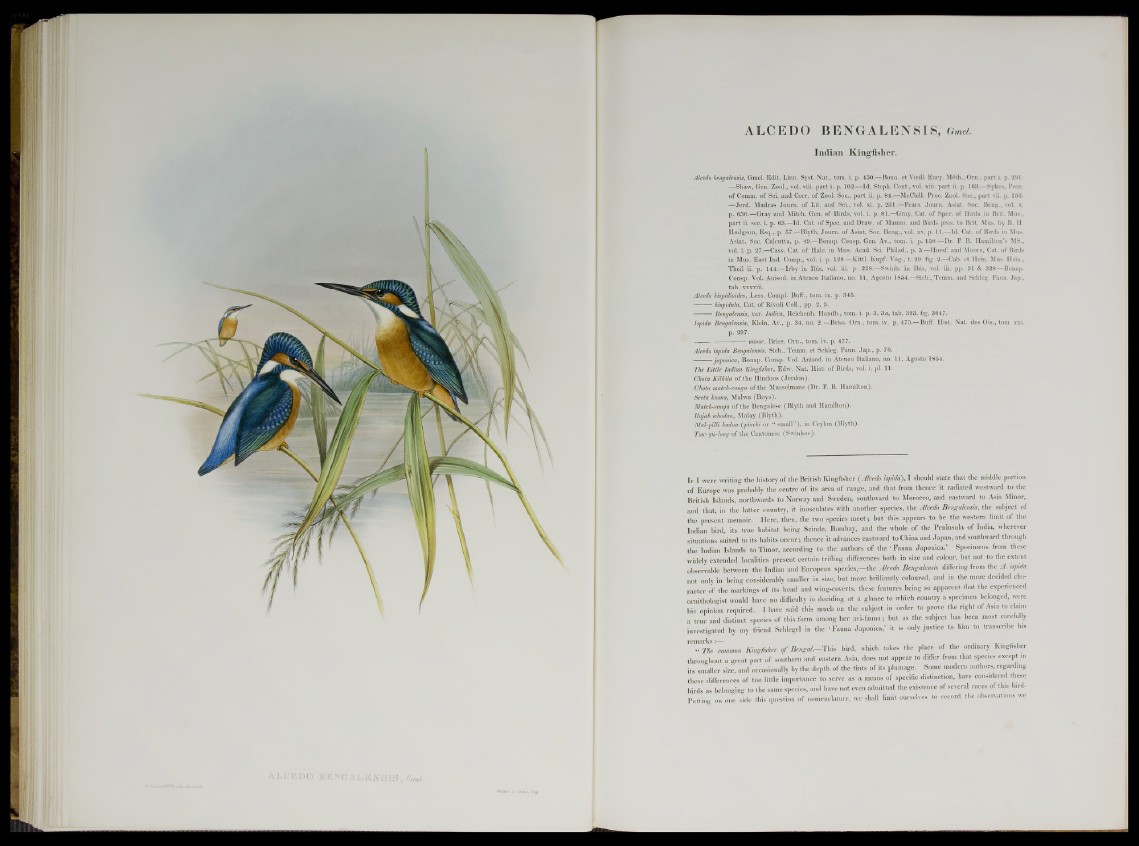

ALCEDO BEN GALEN SIS, gw.

In d ian Kingfisher.

Alcedo hengalensis, Gmel. Edit. Linn. Syst. Nat., tom. i. p. 450.—Bonn, et Vieill. Ency. Méth., Om., part i. p. 291.

—Shaw, Gen. Zool., vol. viii. p art i. p. 102.—Id. Steph. Cont., vol. xiii. p art ii. p. 103.—Sykes, Proc.

of Comm, of Sci. and Corr. of Zool. Soc., p art ii. p. 84.—McClell. Proc. Zool. Soc., part vii. p. 156.

—Jerd. Madras Joum. of Lit. and Sci., vol. xi. p. 231.—Pears. Journ. Asiat. Soc. Beng., vol. x.

p. 636.—Gray and Mitch. Gen. of Birds, vol. i. p. 81.—Gray, Cat. of Spec, of Birds in Brit. Mus.,

part ii. sec. i. p. 63.—Id. Cat. of Spec, and Draw, of Mamm. and Birds pres, to Brit. Mus. by B. II.

Hodgson, Esq., p. 57.—Blyth, Journ. of Asiat. Soc. Beng., vol. xv. p. 11.—Id. Cat. of Birds in Mus.

Asiat. Soc. Calcutta, p. 49.—Bonap. Consp. Gen. Av., tom. i. p. 158—Dr. F. B. Hamilton’s MS.,

vol. i. p. 27.—Cass. Cat. of Hale, in Mus. Acad. Sci. Philad., p. 3.—Horsf. and Moore, Cat. of Birds

in Mus. East Ind. Comp., vol. i. p. 129.—Kittl. Kupf. Vog., t. 29. fig. 2.—Cab. et Hein. Mus. Hein.,

Theil ii. p. 144.—Irby in Ibis, vol. iii. p. 228.—Swinh. in Ibis, vol. iii. pp. 31 & 328.—Bonap.

Consp. Vol. Anisod. in Ateneo Italiano, no. 11, Agosto 1854.—Sieb., Temm. and Schleg. Faun. Jap.,

tab. xxxviii.

Alcedo hispidioides, Less. Compì. Buff., tom. ix. p. 345.

hispidula, Cat. of Rivoli Coll., pp. 2, 3.

■ ■■ Bengalensis, var. Indica, Reichenb. Handb., tom. i. p. 3, 3«, tab. 393. fig. 3047.

Ispida Bengalensis, Klein, Av., p. 34, no. 2 .—Briss. Orn., tom. iv. p. 475*^Buff. Hist. Nat. des Ois., tom xiii.

p. 297.

-------------- minor, Briss. Orn., tom. iv. p. 477.

Alcedo ispida Bengalensis, Sieb., Temm. et Schleg. Faun. Jap., p. 76.

japónica, Bonap. Consp. Vol. Anisod. in Ateneo Italiano, no. 11, Agosto 1854.

The Little Indian Kingfisher, Edw. Nat. Hist, of Birds, vol. i. pi. 11.

Chota Kilkila of the Hindoos (Jerdon).

Chota match-ranga of the Musselmans (Dr. F. B. Hamilton).

Seeta koona, Malwa (Boys).

Match-ranga of the Bengalese (Blyth and Hamilton).

Rajah whodan, Malay (Blyth).

Mal-pilli hudua (pinchi or “ small”) , in Ceylon (Blyth).

Tow-yii-long of the Cantonese (Swinhoe).

If I were writing the history of the British Kingfisher (Alcedo ispidaj, I should state that the middle portion

of Europe was probably the centre of its area of range, and that from thence it radiated westward to the

British Islands, northwards to Norway and Sweden, southward to Morocco, and eastward to Asia Minor,

and that, in the latter country, it inosculates with another species, the Alcedo Bengalensis, the subject of

the present memoir. Here, then, the two species meet; but this appears to be the western limit of the

Indian bird, its true habitat being Scinde, Bombay, and the whole of the Peninsula of India, wherever

situations suited to its habits occur; thence it advances eastward to China and Japan, and southward through

the Indian Islands to Timor, according to the authors of the ‘Fauna Japónica.' Specimens from these

widely extended localities present certain trifling differences both in size and colour, but not to the extent

observable between the Indian and European species,—the Alcedo Bengalensis differing from the A. ispida

not only in being considerably smaller in size, hut more brilliantly coloured, and in the more decided character

of the markings of its head aud wing-coverts, these features being so apparent that the experienced

ornithologist would have no difficulty in deciding at a glance to which country a specimen belonged, were

his opinion required. I have said this much on the subject in order to prove the right of Asia to claim

a true and distinct species of this form among her avi-fauna; but as the subject has been most carefully

investigated by my friend Schlegel in the ‘ Fauna Japónica,’ it is only justice to him to transcribe his

remarks:— ,

« The common Kingfisher o f B e n g a l.-This bird, which takes the place of the ordinary Kingfisher

throughout a great part of southern and eastern Asia, does not appear to differ from that species except in

its smaller size, and occasionally by the depth of the tints of its plumage. Some modern authors, regarding

these differences of too little importance to serve as a means of specific distinction, have considered these

birds as belonging to the same species, and have not even admitted the existence of several races of this bird.

Putting on one side this question of nomenclature, we shall limit ourselves to record the observations we