RHIPIDURA ALBISCAPA, Gould.

White-shafted Fantail.

Rhipidura jlabettifera, Vig. and.Horsf. in Linn. Trans., vol. xv. p. 247, excl. of Syn.—Swains. Nat. Lib. Om., vol. x.;

Flycatchers, p. 124, pi. 10; and Class, of Birds, vol. ii. p. 257.

Rhipidura albiscapa, Gould, in Proc. of Zool. Soc., September 8, 1840.

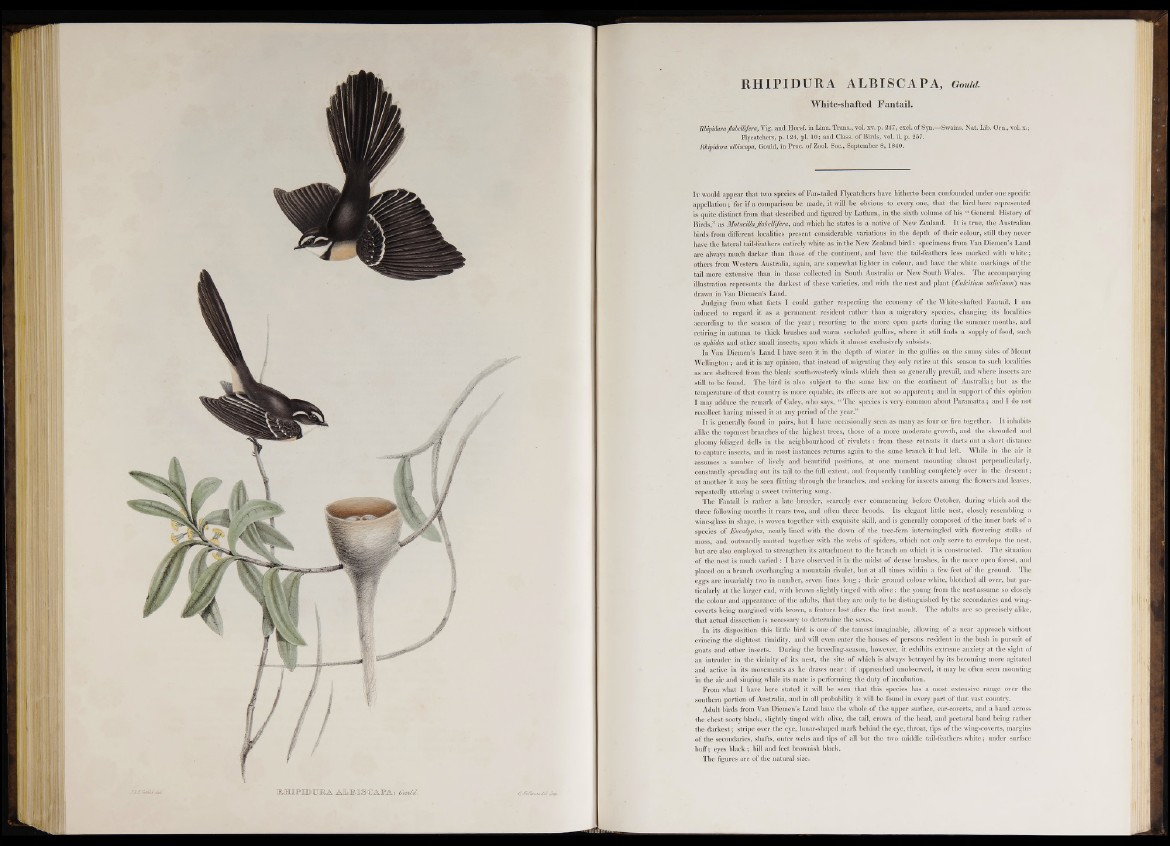

I t would appear that two species o f Fan-tailed Flycatchers have hitherto been confounded under one specific

appellation;’ for if a comparison be made, it will be obvious to everyone, that the bird here represented

is quite distinct from that described and figured by Latham, in the sixth volume of his “ General History of

Birds,” as Motacilla fldbellifera, and which he states is a native o f New Zealand. It is true, the Australian

birds from different localities present considerable variations in the depth o f their colour, still they never

have the lateral tail-feathers entirely white as in the New Zealand b ird: specimens from Van Diemen’s Land

are always much darker than those of the continent, and have the tail-feathers less marked with white;

others from Western Australia, again, are somewhat lighter in colour, and have the white markings of the

tail more extensive than in those collected in South Australia or New South Wales. The accompanying

illustration represents the darkest o f these varieties, and with the nest and plant (Culcitium salicimm') was

drawn in Van Diemen’s Land.

Judging from what facts I could gather respecting the economy o f the White-shafted Fantail, I am

induced to regard it as a permanent resident rather than a migratory species, changing its localities

according to the season o f the year; resorting to the more open parts during the summer months, and

retiring in autumn to thick brushes and warm secluded gullies, where it still finds a supply o f food, such

as aphides and other small insects, upon which it almost exclusively subsists.

In Van Diemen’s Land I have seen it in the depth of winter in the gullies on the sunny sides o f Mount

Wellington; and it is my opinion, that instead of migrating they only retire at this season to such localities

as are sheltered from the bleak south-westerly winds which then so generally prevail, and where insects are

still to be found. The bird is also subject to the same law on the continent o f Australia; but as the

temperature o f that country is more equable, its effects are not so apparent; and in support of this opinion

I may adduce the remark o f Caley, who says, “ The species is very common about Paramatta; and I do not

recollect having missed it at any period o f the year.”

It is generally found in pairs, but I have occasionally seen as many as four or five together. It inhabits

alike the topmost branches o f the highest trees, those o f a more moderate growth, and the shrouded and

gloomy foliaged dells in the neighbourhood of rivulets : from these retreats it darts out a short distance

to capture insects, and in most instances returns again to the same branch it had left. While in the air it

assumes a number o f lively and beautiful positions, at one moment mounting almost perpendicularly,

constantly spreading out its tail to the full extent, and frequently tumbling completely over in the descent;

at another it may be seen flitting through the branches, and seeking for insects among the flowers and leaves,

repeatedly uttering a sweet twittering song.

The Fantail is rather a late breeder, scarcely ever commencing before October, during which and the

three following months it rears two, and often three broods. Its elegant little nest, closely resembling a

wine-glass in shape, is woven together with exquisite skill, and is generally composed of the inner bark o f a

species of Eucalyptus, neatly lined with the down of the tree-fern intermingled with flowering stalks of

moss, and outwardly matted together with the webs of spiders, which not only serve to envelope the nest,

but are also employed to strengthen its attachment to the branch on which it is constructed. The situation

of the nest is much varied : I have observed it in the midst of dense brushes, in the more open forest, and

placed on a branch overhanging a mountain rivulet, but at all times within a few feet o f the ground. The

eggs are invariably two in number, seven lines lon g ; their ground colour white, blotched all over, but particularly

at the larger end, with brown slightly tinged with olive: the young from the nest assume so closely

the colour and appearance o f the adults, that they are only to be distinguished by the secondaries and wing-

coverts being margined with brown, a feature lost after the first moult. The adults are so precisely alike,

that actual dissection is necessary to determine the sexes.

In its disposition this little bird is one of the tamest imaginable, allowing of a near approach without

evincing the slightest timidity, and will even enter the houses of persons resident in the bush in pursuit of

gnats and other insects. During the breeding-season, however, it exhibits extreme anxiety at the sight of

an intruder in the vicinity of its nest, the site of which is always betrayed by its becoming more agitated

and active in its movements as he draws near: if approached unobserved, it may be often seen mounting

in the air and singing while its maté is performing the duty of incubation.

From what I have here stated it will be seen that this species has a most extensive range over the

southern portion of Australia, and in all probability it will be found in every part o f that vast country.

Adult birds from Van Diemen’s Land have the whole of the upper surface, ear-coverts, and a band across

the chest sooty black, slightly tinged with olive, the tail, crown o f the head, and pectoral band being rather

the darkest; stripe over the eye, lunar-sliaped mark behind the eye, throat, tips of the wing-coverts, margins

of the secondaries, shafts, outer webs and tips of all but the two middle tail-feathers white; under surface

buff; eyes black; bill and feet brownish black.

The figures are of the natural size.