P I L a T l SWDD.

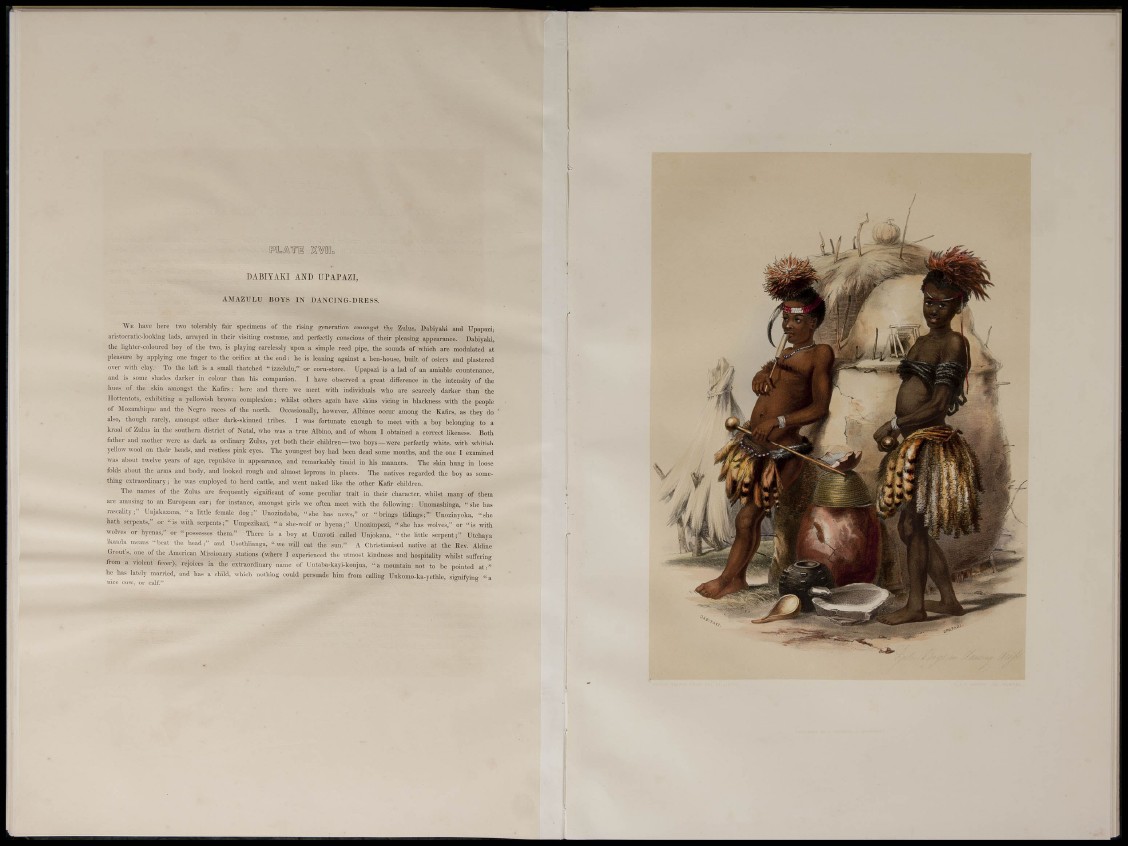

DABIYAKI AND UPAPAZI,

AMAZULU BOYS IN DANOING-DBESS.

WE have here two tolerably fair specimens of the risicg generation amongst the Zulus, Dalnyaki and Upapazi,

aristnnatic-looking lads, arrayed in their visiting costuni6f Jitid pcrfcctlv conscious of their plGdsing cippcsriincc Dabiyjilci

the liglitm--coloured boy of the two, is playing carelessly upon a simple reed pipe, the sounds of which are modulated at

pleasui-e by appljing one fiuger to the orifice at the end: he is leaning against a hen-house, built of osiers and plastered

over with clay. To the left is a small thatched " izzelulu," or corn-store. Upapazi is a lad of an amiable countenance,

mul is some shades darker in colour than his companion. I have observed a great difference in the intensity of the

hue.>5 of the skin amongst the Kafirs; here and there we meet mth individuals who are scarcely darker than the

Hottentots, exhibiting a yellowish b row complexion; whilst others again have skins vieing in blackness with the people

of Mozambique and the Negro races of the north. Occasionally, however, Albinos occur among the Kafirs, as they do "

also, though rarely, amongst other dark-skinned tribes, I was fortunate enough to meet with a boy belonging to a

kraal of Zulus m the southern district of Natal, who was a true Albino, and of whom I obtained a correct likeness. Both

father and mother were a-s dark as ordinary Zulus, yet both their children-two boys—were perfectly white, with wliitish

yellow wool on their heads, and restless pink eyes. The youngest boy had been dead some months, and the one I examined

was about t^^•elve years of 5^;e, repulsive in appearance, and remarkably timid in his manners. The skin hung in loose

folds about the arms and body, and looked rough and almost leprous in places. The natives regarded the boy as something

extraordinary; he was employed to hei-d cattle, and went naked like the other Kafii- children.

The names of the Zulus are frequently significant of some peculiar trait in their character, whilst many of them

are amusing to an European ear; for instance, amongst girls we often meet with the following: Unomashinga, "she has

rascality;" Unjakazana, "a little female dog;" Unozindaba, "she has news," or "brings tidings;" Unozinyoka, "she

hath serpents," or "is vnth serpents;" Umpezikazi, "a she-wolf or hyena;" Unozimpezi, "she has wolves," or "is with

wolves or ¡lyenas," or "possesses them." There is a boy at Umvoti eaUed Uiijokana, "the little serpent;" Utchaya

ikancla nieans "beat the head;" and Usothlianga, "we will eat the sun," A Cbristianised native at the Rev. Aldine

Grout's, one of the American Missionary stations (where I experienced the utmost kindness and hospitality whilst suffering

from a violent fever), rejoices in the extraordinarj' name of Untaba-kayi-konjua, "a mountain not to be pointed at:"

he has lately married, and has a child, which nothing could persuade him from calling Unkorao-ka-yethle, sirmifyine "a

nice cow. or culf," ®