their dépôt. Captain Burton greeted me on arrival

at the old house, and said he had been very anxious

for some time past about our safety, as numerous reports

had been set afloat with regard to the civil wars

we had had to circumvent, which had impressed the

Arabs as well as himself with alarming fears. I

laughed over the matter, but expressed my regret that

he did not accompany me, as I felt quite certain in

my mind I had discovered the source of the Nile.

This he naturally objected to, even after hearing all

my reasons for saying so, and therefore the subject was

dropped. Nevertheless, the Captain accepted all my

geography leading from Kazé to the Nile, and wrote

it down in his book—contracting only my distances,

which he said he thought were exaggerated, and of

course taking care to sever my lake from the Nile by

his Mountains of the Moon.

I t affords me great pleasure to be able to report the

safe return of the expedition in a state of high spirits

and gratification. All enjoyed the salubrity of the

climate, the kind entertainments of the sultans, the

variety and richness of the country, and the excellent

fare everywhere. Further, the Beluches, by their exemplary

conduct, proved themselves a most efficient,

willing, and trustworthy guard, and are deserving of

proved to be much, more healthy than any of those parts of Africa subjected

to periodical seasons. Next to this scheme, I would recommend

this fertile zone to be attacked from Gondokoro on the Nile, and from

Gaboon (the French port) on the equator. The Gondokoro line, being

known to a considerable extent, is ready for working, and only requires

government protection to make it succeed ; but the other line from

the Gaboon should first be inspected by a scientific expedition.

the highest encomiums; they, with Bombay, were

the life and success of everything, and I sincerely

hope they may not be forgotten.

The Arabs told me I could reach the N’yanza in

fifteen to seventeen marches, and I returned in sixteen,

although I had to take a circuitous line instead

of a direct one. The provisions, too, just held out.

I took a supply for six weeks, and completed that

time this day. The total road-distance there and back

is 452 miles, which, admitting that the Arabs make

sixteen marches of it, gives them a marching rate of

more than fourteen miles a-day.

The temperature is greater at this than at any other

time of the year, in consequence of its being the end

of the dry season; still, as will be seen by the annexed

register of one week, the Unyamudzi plateau is not

unbearably hot.

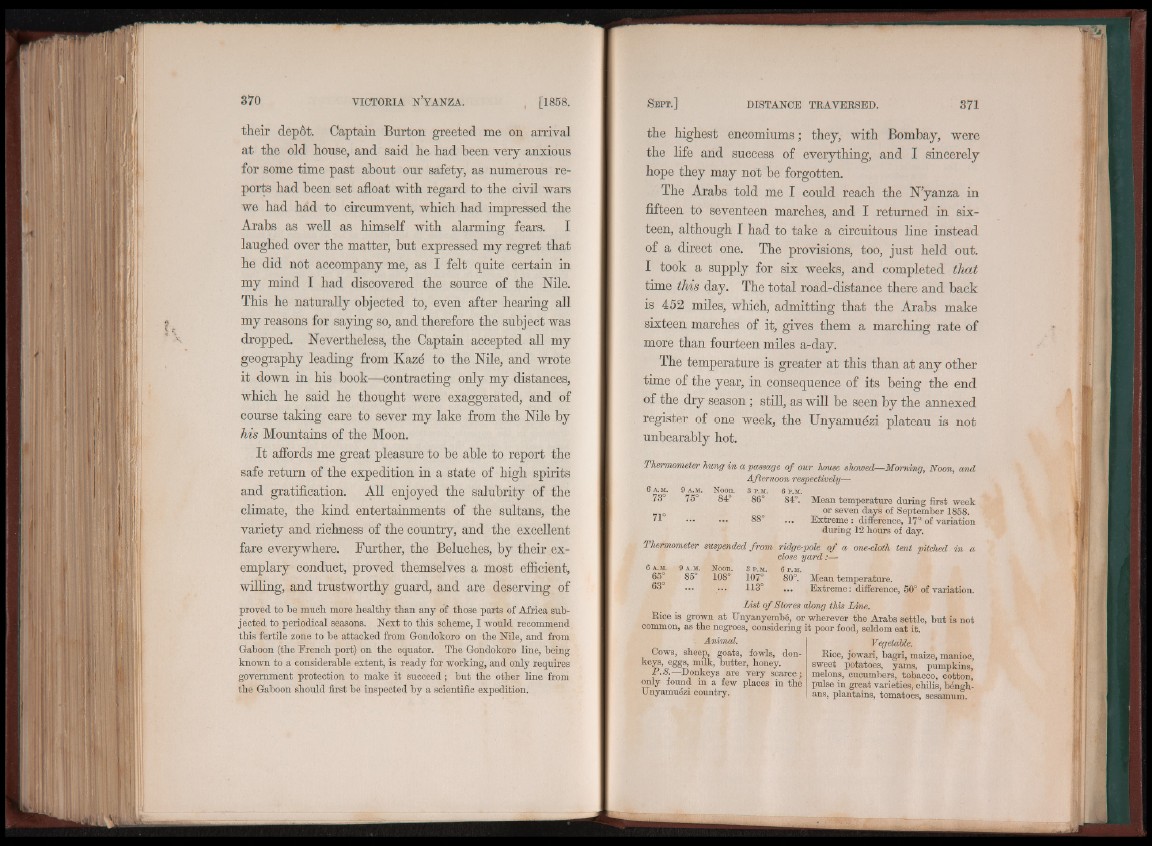

Thermometer hung in a passage of our house showed—Morning, Noon, and

Afternoon respectively—

6 a .m. 9 a .m. N o o n . 3 p .m . 6 p .m .

73° 75° 84° 86° 84°. Mean temperature during first week

^ o or seven days of September 1858.

' ••• ••• 38 ... Extreme: difference, 17° of variation

during 12 bours of day.

Thermometer suspended from ridge-pole of a one-cloth tent pitched in a

close yard:—

6 a .m. 9 a .m. N o o n . 3 p .m. 6 p .m .

65q 85° 108° 107° 80°. Mean temperature.

63 ••• ,••• 113° ... Extreme: difference, 50° of variation.

List of Stores along this Line.

Rice is grown at Unyanyembg, or wherever the Arabs settle, but is not

common, as the negroes, considering it poor food, seldom eat it.

. Animal.

Cows, sheep, goats, fowls, donkeys,

eggs, milk, butter, honey.

P.S.—Donkeys are very scarce;

only found in a few places in the

0 rryamuezi country.

Vegetable.

Rice, jowari, bagri, maize, manioc,

sweet potatoes, yams, pumpkins,

melons, cucumbers, tobacco, cotton,

pulse in great varieties, chilis, béngh-

ans, plantains, tomatoes, sesamum.