interstices, but always in the same plane, so that at last there is a circle of eight eggs all standing upright in the

sand with several inches of sand intervening between each. The male bird assists the female in opening and

covering up the mound; and provided the birds are not themselves disturbed, the female continues to lay in the

same mound, even after it has been several times robbed. The natives say that the females lay an egg every day.

“ Eight is the greatest number I have heard of from good authority as having been found in one n e s t; but I

opened a mound which had been previously robbed of several eggs, and found that two had been laid opposite to

each other in the same plane in the usual manner; and a third deposited in a plane parallel to that in which the

other two were placed, but inches below them. This circumstance led me to imagine it was possible that there

might be sometimes successive circles of eggs in different planes.

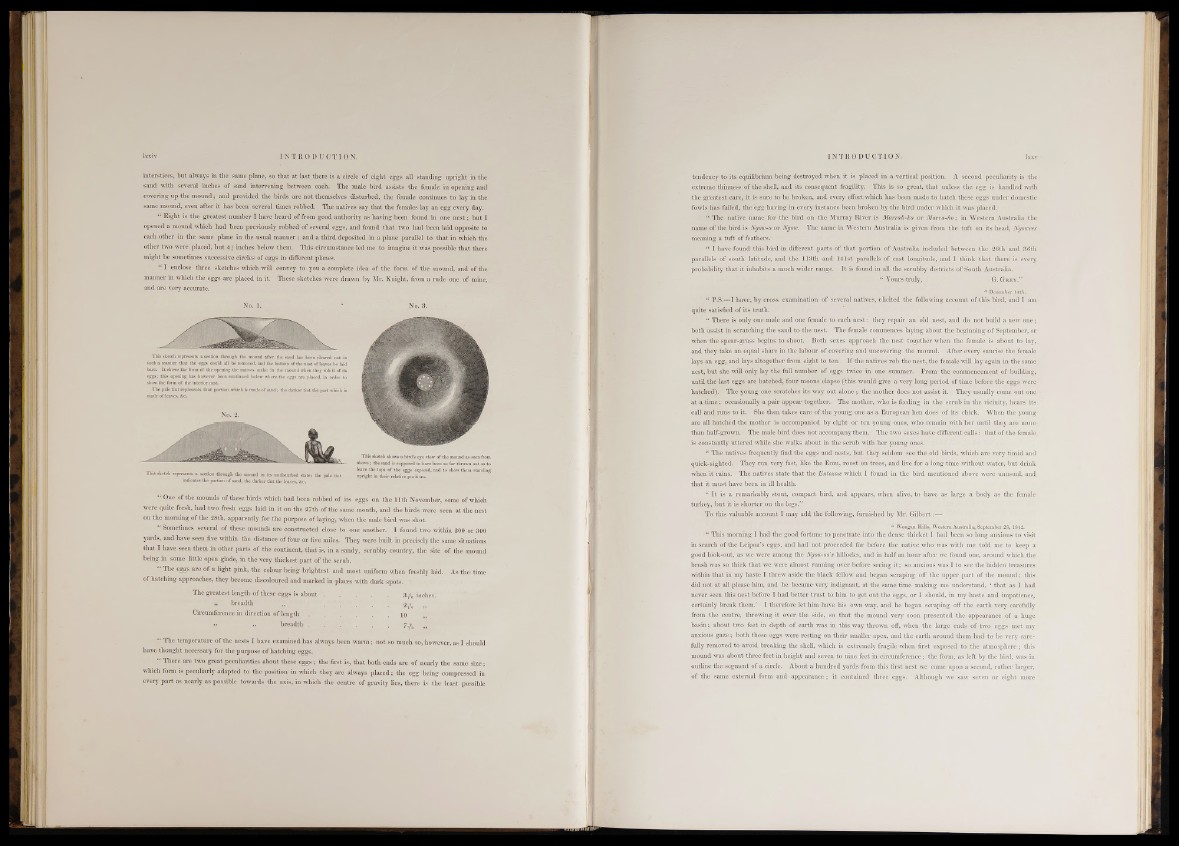

“ I enclose three sketches which will convey to you a complete idea of the form o f the mound, and of the

manner in which the eggs are placed in it. These sketches were drawn by Mr. Knight, from a rude one of mine,

and are very accurate.

“ l |l § of the mounds of these birds which had been robbed of its eggs on the 1 1 th November, some of which

were quite fresh, had two fresh eggs laid in it on the 27th of the same month, and the birds were seen at the nest

on the morning of the 28th, apparently for the purpose of laying, when the male bird was shot.

“ Sometimes several of these mounds are constructed close to one another. I found two within 200 or 300

yards, and have seen five within the distance of four or five miles. They were built in precisely the same situations

that I have seen them in other parts of the continent, that- is, in a sandy, scrubby country, the site of the mound

being in some little open glade, in the very thickest p art of the scrub.

“ The eSSs are of a Pink> the colour being brightest and most uniform when freshly laid. As the time

of hatching approaches, they become discoloured and marked in places with dark spots. '

The greatest length of these eggs is a b o u t 3 [«u inches.

I breadth „ . . . . . o*

Circumference in direction of l e n g t h ................................................. 10

» „ breadth . . . . . . 7-a

“ The temperature of the nests I have examined has always been warm; not so much so, however, as I should

have thought necessary for the purpose of hatching eggs.

“ There are two great peculiarities about these eggs; the first is, that both ends are of nearly the same size;

which form is peculiarly adapted to the position in which they are always placed; the egg being compressed in

every part as nearly as possible towards the axis, in which the centre of gravity lies, there is the least possible

tendency to its equilibrium being destroyed when it is placed in a vertical position. A second peculiarity is the

extreme thinness of the shell, and its consequent fragility. This is so great, that unless the egg is handled with

the greatest care, it is sure to be-broken, and every effort which has been made to hatch these eggs under domestic

fowls has failed, the-egg having in every instance been broken by the bird under which it was placed.

“ The native name for the bird on the Murray River is Marrak-ko or Marrq-ko ; in Western Australia the

name of the bird is Ngow-o or Ngow. The name in Western Australia is given from the tuft on its head, Ngoweer

meaning a tuft of feathers. :

“ I have found this bird in different parts, of that portion of Australia included between the 26th and 36th

parallels of south latitude, and the. 113th and 141st parallels of east longitude, and I think that there is every

probability that it inhabits a much wider, range. I t is found in all the scrubby districts* of South Australia.

“ Yours truly,. G. Grey.”

« December 14th.

“ P.S.—I have, by cross examination of several natives, elicited the following account of this bird, and I am •

quite satisfied of its truth.

“ There is only one male and one female to each nest : they repair an old nest, and do not build a new one ;

both assist in scratching the sand to the nest. The female commences laying about the beginning7 of September, or

when the spear-grass begins to shoot. Both sexes approach the nest togethér when the female is about to lay,.

and they take an equal share in the labour of covering and uncovering the mound. After every sunrise the female

lays an egg, and lays altogether from eight to ten. If the natives rob the nest, the female will lay again in the same :

nest, but she will only lay the full number of eggs twice in one summer. From the Commencement of building,

until the last eggs are hatched, four moons elapse (this would give a very long period of time before the eggs were-

hatched).' The young one scratches its way out alone ; the mother does not assist it. They usually come out one

a t a time; occasionally a pair appear together.. The mother, who is feeding in the scrub in the vicinity,,hears its;

call and runs to it. She then takes care of the young one as:a European hen does of, its chick. When the young-

are all hatched the mother is accompanied by eight or. ten young ones, who remain with her until they are more:

than half-grown. The male bird does not accompany them. . The two sexes have different calls : that of the female*

is constantly uttered while she walks about in the scrub with her young ones.

“ The natives frequently find the eggs and nests, but they seldom see'thé old birds, which are very timid and

quick-sighted. They run very fast, like the Emu, roost on-trees, and live for a long time without water, but drink

when it rains. The natives state that the Entozoce which I found in the bird mentioned above were -unusual, and

that it must have been in ill health.-

“ I t is a remarkably stout, compact bird, and appears, when alive, to have as: large a body as the female

turkey, b u t it is shorter on the legs.”

To this valuable account I may add. the following, furnished by Mr. Gilbert :—

“ Wongan Hills, Western Australia, September 28, 1842.

“ This morning I had the good fortune to penetrate into the dense thicket I had been so long anxious to visit

in search of the Lèipoa’s eggs, and had not proceeded far- before the native who was with me told me to keep a

good lo’ok-out, as we were among the Ngou-oo's hillocks, and in half an hour after we found one, around which, the

brush was so thick that we were almost running over before seeing it; so anxious was I to see the hidden treasures

within that in my haste I threw aside the black fellow and began scraping off the upper part of the mound ; this

did not at all please him, and he became very indignant, at the same time making me understand, ‘ that as I had

never seen this nest before I had better trust to him to get out the eggs, or I should, in my haste and impatience,

certainly break them.’ I therefore let him have his own way, and he began scraping off the earth very carefully

from the centre, throwing it over the side, so that the mound very soon presented the appearance of a huge

basin; about two feet in depth of earth was in this way thrown off, when the large ends of two eggs met my

anxious gaze ; both these eggs were resting on their smaller apex, and the earth around them had to be very carefully

removed to avoid breaking the shell, which-is extremely fragile when first exposed to the atmosphere ; this

mound was about three feet in height and seven to nine feet in circumference ; the form, as left by the bird, was in

outline the segment of a circle. About a hundred yards from this first nest we came upon a second, rather larger,

of the ‘ same external form and appearance ; it contained three, eggs. Although we saw seven or eight more