Haarlem’s main canals. This meant that the museum premises would become accessible from

two sides. The entire conglomerate of museum buildings - Teyler’s old town house, the Oval

Room, the First Art Gallery and the newest annex - now sort of snaked their way through the

block of houses of which Teyler’s own house formed a part. Crucially, as a result, it now

became possible to render the inconspicuous access route through Teyler’s old house a back

entrance rather than the main entrance, by constructing a second, purpose-built entrance on

“the other side” of the complex of buildings.

It seems that — in architectural terms — the mastermind behind these plans was the trustee L.P.

Zocher, who was himself an accomplished architect. Over the course of his career he was

involved in designing a number of mansions in Haarlem, some of them together with his even

better known father, Jan David Zocher.25 At any rate it was the younger Zocher who drew up

the detailed requirements the entrants to the architectural competition were provided with.26 It

is plausible that in drawing up the plans for the competition he might also have consulted

another architect, Jacob Ernst van den Arend, who at this point was working part-time for

Teylers Museum as caretaker of its buildings. In 1862 van den Arend had designed Haarlem’s

town museum in the town house (Stadhuis), where the paintings by Frans Hals that were

owned by the municipality were put on display.27 So he was no stranger to designing

exhibition areas. Furthermore, he cooperated with Zocher on at least one project in Haarlem.

And in the early 1890s, van den Arend designed the next extension to Teylers Museum, the

so-called Second Art Gallery, adjacent to the First Art Gallery.29

Ultimately, the amount of detail provided by the trustees meant that the only part left entirely

to the architects’ imagination was the entrance façade facing the street, i.e. the entrance area

to the building. The trustees stated somewhat ominously that “[t]he façade facing the Spaame

must, as the main entrance, be worthy of the [Teyler] foundation”.

This implies that they were well aware just how important this part of the building was going

to beB as, indeed, does the unfolding of subsequent events.31 Because, in a nutshell, all the

trustees retained from the architectural competition was the design of the museum’s entrance

façade. They decided not to award any of the entrants the full prize money, but did single out

two designs and offered the author of one of them - the comparatively young architect

Christian Ulrich from Vienna - the sum of f5000,- to be allowed to use his design for the

entrance façade. Ulrich agreed and provided numerous depictions of possible slight variations

to his original design, along with a detailed scale model of the museum’s entrance area as he

wanted to build it. Zocher even travelled to Vienna to pick up this model and discuss Ulrich’s

plans in person in February 1879.

25 See: Wim de Wagt and Jos Fielmich, Architectuurgids Haarlem (Rotterdam: Uitgeverij 010, 2005), 77 & 89.

26 Gestel and Reinink, “Het ‘nieuwe museum’ van Teyler (1877-1885),” 227.

27 Saskia Groot Koerkamp, “Teylers Tweede Schilderijenzaal: Mee Met de Tijd” (bachelor thesis, Utrecht

University, 2011).

28 Wagt and Fielmich, Architectuurgids Haarlem, 80.

Koerkamp, ‘Teylers Tweede Schilderijenzaal: Mee Met de Tijd.”

30 “De gevel aan het Spaame moet, als hoofdingang, der stichting waardig zijn” ; as quoted in: Gestel and

Reinink, “Het ‘nieuwe museum’ van Teyler (1877-1885),” 228.

31 The following account is based on the information provided in: Gestel and Reinink, “Het ‘nieuwe museum’

van T eyler (1877-1885).”

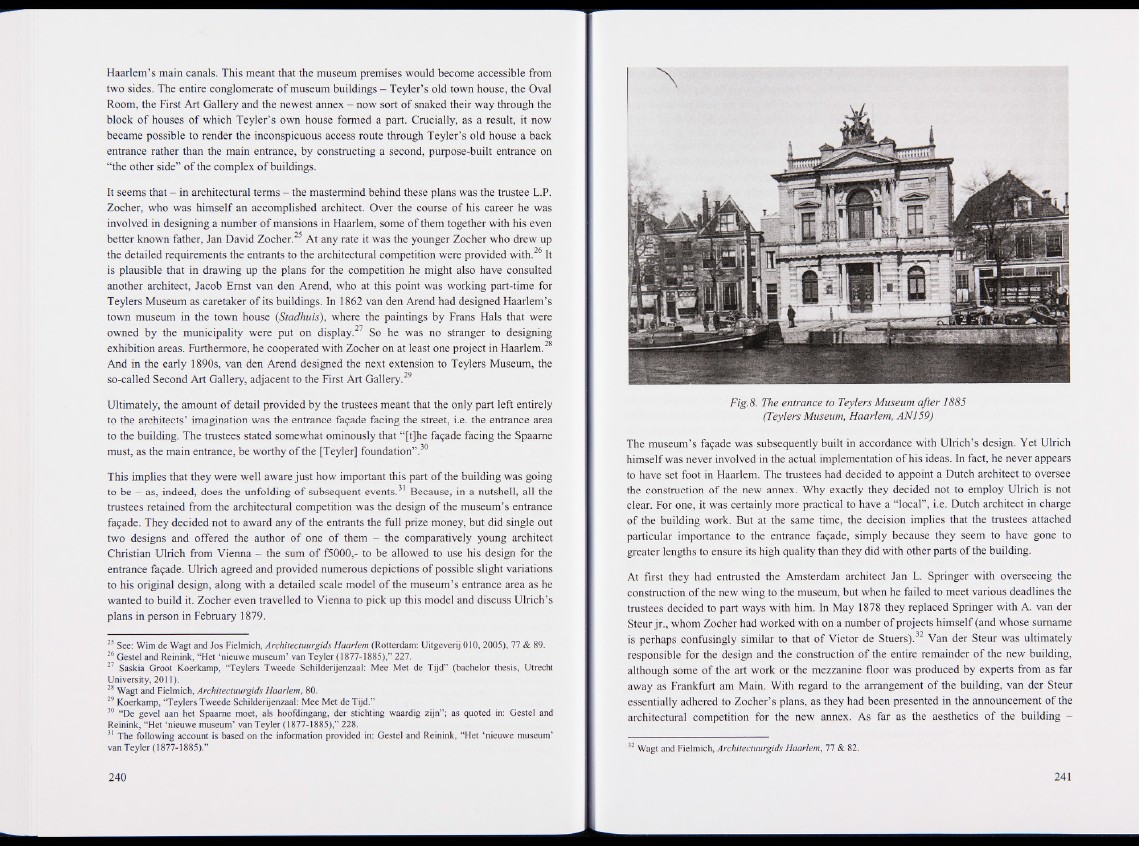

Fig. 8. The entrance to Teylers Museum after 1885

(Teylers Museum, Haarlem, AN159)

The museum’s façade was subsequently built in accordance with Ulrich’s design. Yet Ulrich

himself was never involved in the actual implementation of his ideas. In fact, he never appears

to have set foot in Haarlem. The trustees had decided to appoint a Dutch architect to oversee

the construction of the new annex. Why exactly they decided not to employ Ulrich is not

clear. For one, it was certainly more practical to have a “local”, i.e. Dutch architect in charge

of the building work. But at the same time, the decision implies that the trustees attached

particular importance to the entrance façade, simply because they seem to have gone to

greater lengths to ensure its high quality than they did with other parts of the building.

At first they had entrusted the Amsterdam architect Jan L. Springer with overseeing the

construction of the new wing to the museum, but when he failed to meet various deadlines the

trustees decided to part ways with him. In May 1878 they replaced Springer with A. van der

Steur jr., whom Zocher had worked with on a number of projects himself (and whose surname

is perhaps confusingly similar to that of Victor de Stuers).32 Van der Steur was ultimately

responsible for the design and the construction of the entire remainder of the new building,

although some of the art work or the mezzanine floor was produced by experts from as far

away as Frankfort am Main. With regard to the arrangement of the building, van der Steur

essentially adhered to Zocher’s plans, as they had been presented in the announcement of the

architectural competition for the new annex. As far as the aesthetics of the building B

32 Wagt and Fielmich, Architectuurgids Haarlem, 77 & 82.