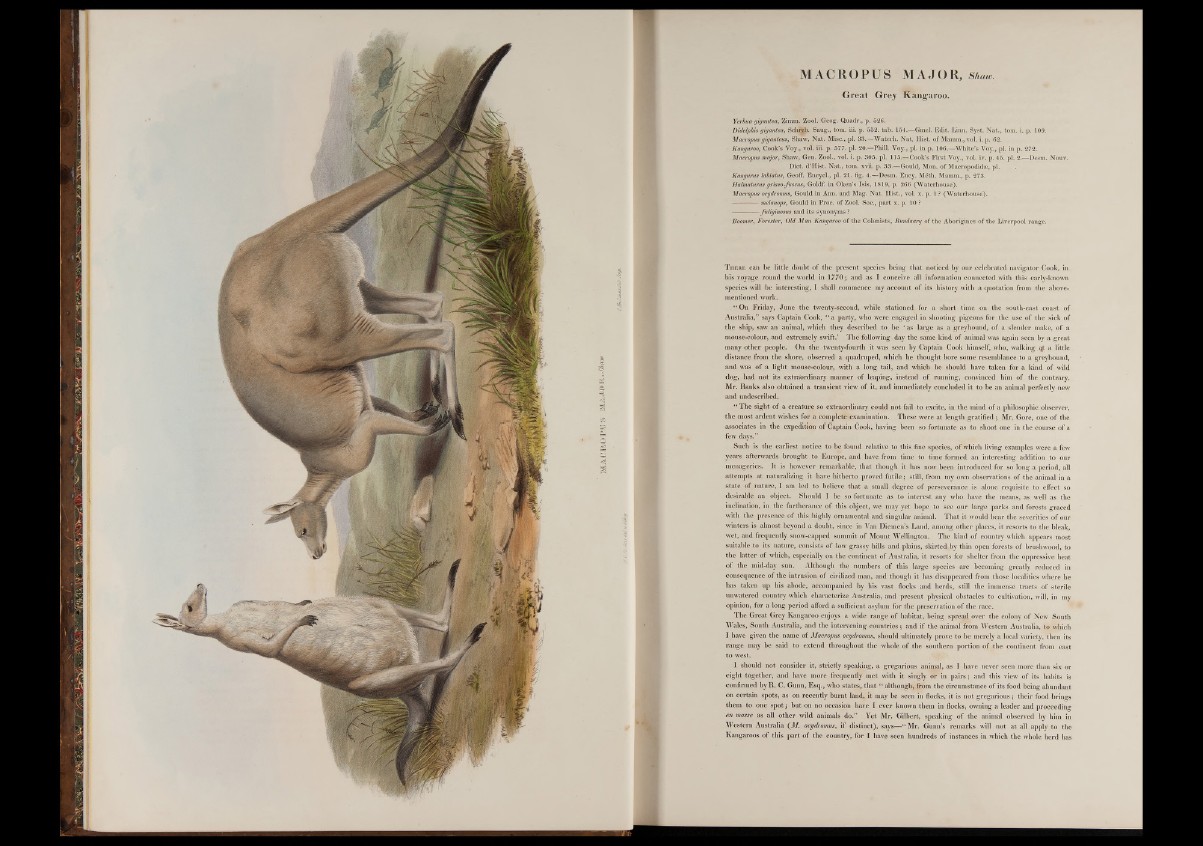

MACROPUS MAJOR, Shaw.

Great Grey Kangaroo.

Yerbua gigantea, Zimm. Zool. Geog. Quadr., p. 526.

Didelphis gigantea, Schf&b. Saug., tom. iii. p. 552. tab. 154.—Gmel. Edit. Linn. Syst. Nat., tom. i. p. 109.

Macropus gigatiteus, Shaw, Nat. Misc., pi. 33.—Waterh. Nat. Hist, of Mamm., vol. i. p. 62. .

Kangaroo, Cook’s Voy., vol. iii. p. 577.-pl> 20.—Phill. Voy., pi. in p. 106.—White’s Voy., pi. in p. 272.

Macropus major, Shaw, Gen. Zool., vol. i. p. 305. pi. 115.—Cook’s First Voy., vol. iv. p. 45. pi. 2.—Desm. Nouv.

Diet. d’Hist. Nat., tom. xvii. p. 33.—Gould, Mon. of Macropodidee, pi.

Kängurus labiatus, Geoff. Encycl., pi. 21. fig. 4.—Desm. Ency. M6th. Mamm., p. 273.

Halmaturus griseo-fuscus, Goldf. in Öken’s Isis, 1819, p. 266 (Waterhouse).

Macropus ocgdromus, Gould in Ann. and Mag. Nat. Hist., vol. x. p. 1 ? (Waterhouse).

------------melanops, Gould in Proc. of Zool. Soc., part x. p. 10 ?

------------fuliginosus and its synonyms ?

Boomer, Forester, Old Man Kangaroo of the Colonists, Bundaary of the Aborigines of the Liverpool range.

T h e r e can be little doubt of the present species being that noticed by our celebrated navigator Cook, in

his voyage round the world in 1770 ; and as I conceive all information connected with this early-known

species will be interesting, I shall commence my account of its history with a quotation from the abover

mentioned work.

“ On Friday, June the twenty-second, while stationed for a short time on the south-east coast of

Australia,” says Captain Cook, “ a party,, who were engaged in shooting pigeons for the use of the sick of

the ship, saw an animal, which they described to be ‘as large as a greyhound, of a slender make, of a

mouse-colour, and extremely swift.’ The following day the same kind of animal was again seen by a great

many other people. On the twenty-fourth it was seen by Captain Cook himself, who, walking qjt a little

distance from the shore, observed a quadruped, which he thought bore some resemblance to a greyhound,

and was of a light mouse-colour, with a long tail, and which he should have taken for a kind of wild

dog, had not its extraordinary manner of leaping, instead of running, convinced him of the contrary.

Mr. Banks also obtained a transient view of it, and immediately concluded it to be an animal perfectly new

and undescribed.

“ The sight of a creature so extraordinary could not fail to excite, in the mind of a philosophic observer,

the most ardent wishes for a complete examination. These were at length gratified ; Mr. Gore, one of the

associates in the expedition of Captain Cook, having been so fortunate as to shoot one in the course of a

few days.”

Such is the earliest notice to be found relative to this fine species, of which living examples were a few

years afterwards brought to Europe, and have from time to time formed an interesting addition to our

menageries. It is however remarkable, that though it has now been introduced for so long a period, all

attempts at naturalizing it have hitherto proved futile; still, from my own observations of the animal in a

state of nature, I am led to believe that a small degree of perseverance is alone requisite to effect so

desirable an object. Should I be so fortunate as to interest any who have the means, as well as the

inclination, in the furtherance of this object, we may yet hope to see our large parks and forests graced

with the presence of this highly ornamental and singular animal. That it would bear the severities of our

winters is almost beyond a doubt, since in Van Diemen’s Land, among other places, it resorts to the bleak,

wet, and frequently snow-capped summit of Mount Wellington. The kind of country which appears most

suitable to its nature, consists of low grassy hills and plains, skirted,by thin open forests of brushwood, to

the latter of which, especially on the continent of Australia, it resorts for shelter from the oppressive heat

of the mid-day sun. Although the numbers of this large species are becoming greatly reduced in

consequence of the intrusion of civilized man, and though it has disappeared from those localities where he

has taken up his abode, accompanied by his vast flocks and herds, still the immense tracts of sterile

unwatered country which characterize Australia, and present physical obstacles to cultivation, will, in my

opinion, for a long period afford a sufficient asylum for the preservation of the race.

The Great Grey Kangaroo enjoys a wide range of habitat, being spread over the colony of New South

Wales, South Australia, and the intervening countries; and if the animal from Western Australia, to which

I have given the name of Macropus ocydromus, should ultimately prove to be merely a local variety, then its

range may be said to extend throughout the whole of the southern portion of the continent from east

to west.

I should not consider it, strictly speaking, a gregarious animal, as I have never seen more than six or

eight together, and have more frequently met with it singly or in pairs; and this view of its habits is

confirmed by R. C. Gunn, Esq., who states, that “ although, from the circumstance of its food being abundant

on certain spots, as on recently burnt laud, it may be seen in flocks, it is not gregarious; their food brings

them to one spot; but on no occasion have I ever known them in flocks, owning a leader and proceeding

en masse as all other wild animals do.” Yet Mr. Gilbert, speaking of the animal observed by him in

Western Australia (M. ocydromus, if distinct), says—“ Mr. Gunn’s remarks will not at all apply to the

Kangaroos of this part of the country, for I have seen hundreds of instances in which the whole herd has