TRIONYX LABIATUS.

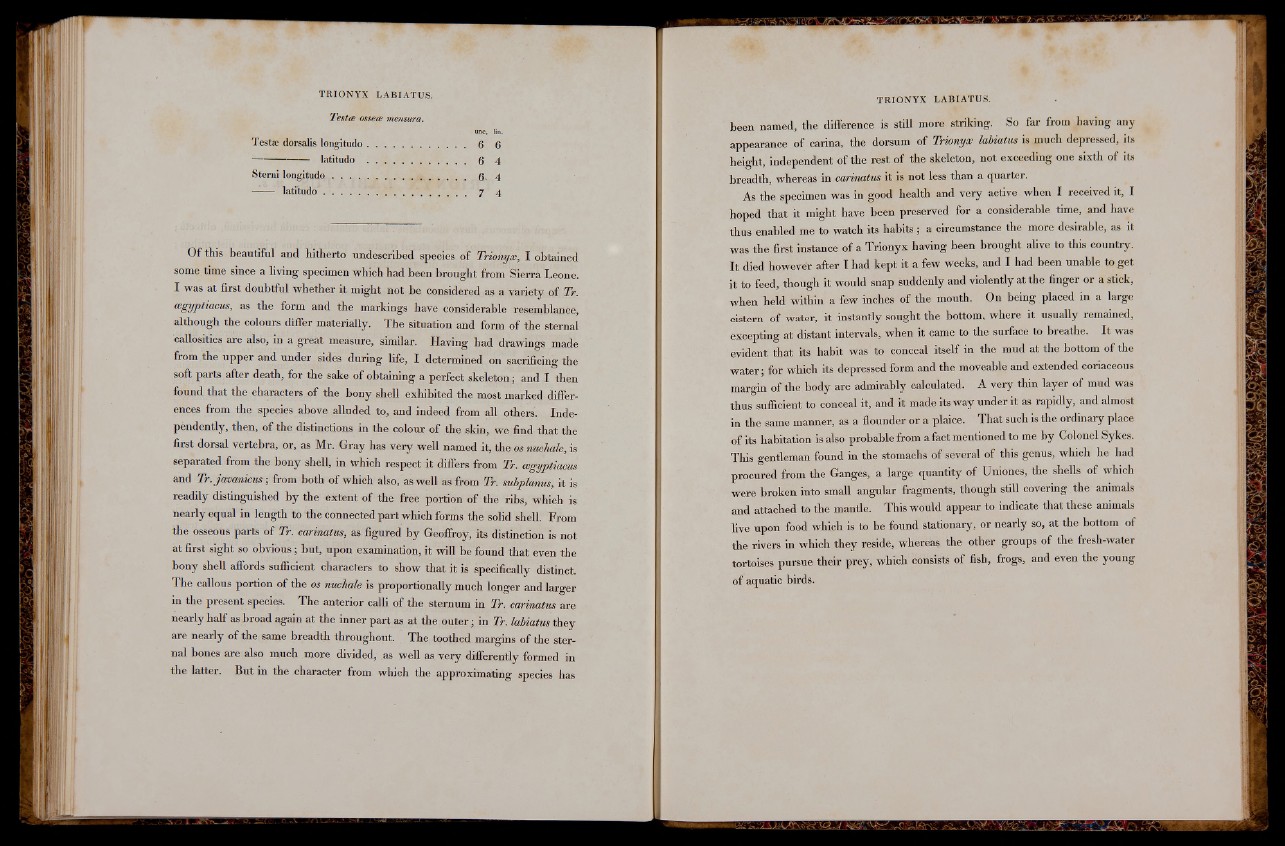

Testce ossece metisura.

■ »me. lin.

Testae dorsalis longitudo.......................................... 6 g

----------------------la titu d o ......................................................... 6 4

Sterni lo n g itu d o ..................... . . . . . . ..................... 6> 4

l a t i t u d o ................................................. 7 4

Of this beautiful and hitherto undescribed species of Trionyx, I obtained

some time since a living specimen which had been brought from Sierra Leone.

I was at first doubtful whether it might not be considered as a variety of Tr.

wgyptiucus, as the form and the markings have considerable resemblance,

although the colours differ materially. The situation and form of the sternal

callosities are also, in a great measure, similar. Having had drawings made

from the upper and under sides during life, I determined on sacrificing the

soft parts after death, for the sake of obtaining a perfect skeleton; and I then

found that the characters of the bony shell exhibited the most marked differences

from the species above alluded to, and indeed from all others'. Independently,

then, of the distinctions in the colour of the skin, we find that the

first dorsal vertebra, or, as Mr. Gray has very well named it, the os nuchale, is

separated from the bony shell, in which respect it differs from Tr. agyptiacus

and Tr. javanicus; from both of which also, as well as from Tr. subplanus, it is

readily distinguished by the extent of the free portion of the ribs, which is

nearly equal in length to the connected part which forms the solid shell. From

the osseous parts of Tr. carinatus, as figured by Geoffroy, its distinction is not

at first sight so obvious; but, upon examination, it will be found that even the

bony shell affords sufficient characters to show that it is specifically distinct.

The callous portion of the os nuchale is proportionally much longer and larger

in the present species. The anterior calli of the sternum in Tr. carinatus are

nearly half as broad again at the inner part as at the outer; in Tr. labiatus they

are nearly of the same breadth throughout. The toothed margin» 0f the sternal

bones are also much more divided, as well as very differently formed in

the latter. But in the character from which the approximating species has

TRIONYX LABIATUS.

been named, the difference is still more striking. So far from having any

appearance of carina, the dorsum of Trionyx labiatus is much depressed, its

height, independent of the rest of the skeleton, not exceeding one sixth of its

breadth, whereas in carinatus it is not less than a quarter.

As the specimen was in good health and very active when I received it, I

hoped that it might have been preserved for a considerable time, and have

thus enabled me to watch its habits; a circumstance the more desirable, as it

was the first instance of a Trionyx having been brought alive to this country.

It died howeve'r after I had kept it a few weeks, and I had been unable to get

it to feed, though it would snap suddenly and violently at the finger or a stick,

when held within a few inches of the mouth. On being placed in a large

cistern of water, it instantly sought the bottom, where it usually remained,

excepting at distant intervals, when it came to the surface to breathe. It was

evident that its habit was to conceal itself in the mud at the bottom of the

water; for which its depressed form and the moveable and extended coriaceous

margin of the body are admirably calculated. A very thin layer of mud was

thus sufficient to conceal it, and it made its way under it as rapidly, and almost

in the same manner, as a flounder or a plaice;: That such is the ordinary place

of its habitation is also probable from a fact mentioned to me by Colonel Sykes.

This gentleman found in the stomachs of several of this genus, which he had

procured from the Ganges, a large quantity of Uniones, the shells of which

were broken into small angular fragments, though still covering the animals

and attached to the mantle. This would appear to indicate that these animals

live upon food which is to be found stationary, or nearly so, at the bottom of

the rivers in which they reside, whereas the other groups of the fresh-water

tortoises pursue their prey, which consists of fish, frogs, and even the young

of aquatic birds.