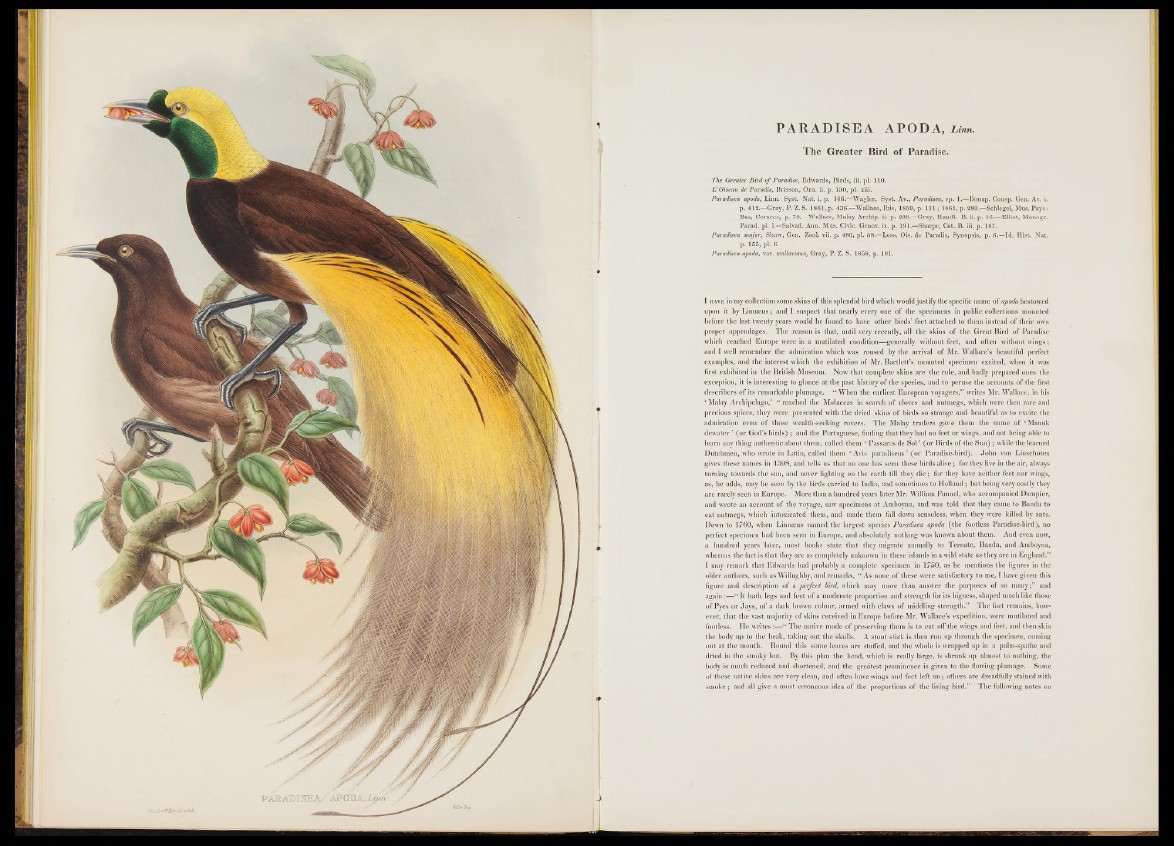

The Greater Bird of Paradise.

The Greater Bird o f Paradise, Edwards, Birds, iii. pi. 110.

L ’Oiseau de Paradis, Brisson, Om. ii. p. 130, pi. xiii.

Paradisea apoda, Linn. Syst. Nat. i. p. 166.—Wagler, Syst. Av., Paradisea, sp. 1.—Bonap. Consp. Gen. Av. i.

p. 412.—Gray, P. Z. S. 1861, p . 436.—Wallace, Ibis, 1859, p. I l l ; 1861, p. 289.—Schlegel, Mus. Pays-

Bas, Coraces, p. 78.—Wallace, Malay Archip. ii. p. 238.—Gray, Handl. B. ii. p. 16.—Elliot, Monogr.

Parad. pi. i.—Salvad. Ann. Mus. Civic. Genov, ix. p. 191.—Sharpe, Cat. B. iii. p. 167.

Paradisea major, Shaw, Gen. Zool. vii. p. 480, pi. 68.—Less. Ois. de Paradis, Synopsis, p. 6.—Id. Hist. Nat.

p. 155, pi. 6.

Paradisea apoda, var. wallaciana, Gray, P. Z. S. 1858, p. 181.

I have in my collection some skins o f this splendid bird which would justify the specific name o f apoda bestowed

upon it by Linnaeus; and I suspect tliat nearly every one o f the specimens in public collections mounted

before the last twenty years would be found to have other birds’ feet attached to them instead of their own

proper appendages. The reason is that, until very recently, all the skins o f the Great Bird o f Paradise

which reached Europe were in a mutilated condition—generally without feet, and often without wings;

and I well remember the admiration which was roused by the arrival o f Mr. Wallace’s beautiful perfect

examples, and the interest which the exhibition of Mr. Bartlett’s mounted specimen excited, when it was

first exhibited in the British Museum. Now that complete skins are the rule, and badly prepared ones the

exception, it is interesting to glance at the past history o f the species, and to peruse the accounts o f the first

describers o f its remarkable plumage. “ When the earliest European voyagers,” writes Mr. Wallace, in his

‘ Malay Archipelago,’ “ reached the Moluccas in search o f cloves and nutmegs, which were then rare and

precious spices, they were presented with the dried skins o f birds so strange and beautiful as to excite the

admiration even, o f those wealth-seeking rovers. The Malay traders gave them the name o f ‘ Manuk

dewater ’ (or God’s birds) ; and the Portuguese, finding that they had no feet or wings, and not being able to

learn any thing authentic about them, called them ‘ Passaros de Sol ’ (or Birds of the S u n ); while the learned

Dutchmen, who wrote in Latin, called them ‘ Avis paradiseus ’ (or Paradise-bird). John van Linschoten

gives these names in 1598, and tells us that no one has seen these birds alive; for they live in the air, always

turning towards the sun, and never lighting on the earth till they d ie ; for they have neither feet nor wings,

as, he adds, may be seen by tbe birds carried to India, and sometimes to Holland; but being very costly they

are rarely seen in Europe. More than a hundred years later Mr. William Funnel, who accompanied Dampier,

and wrote an account o f the voyage, saw specimens at Amboyna, and was told that they came to Banda to

eat nutmegs, which intoxicated them, and made them fall down senseless, when they were killed by ants.

Down to 1760, when Linnaeus named the largest species Paradisea apoda (the footless Paradise-bird), no

perfect specimen had been seen in Europe, and absolutely nothing was known about them. And even now,

a hundred years later, most books state that they migrate annually to Ternate, Banda, and Amboyna,

whereas the fact is that they are as completely unknown in these islands in a wild state as they are in England.”

I may remark that Edwards had probably a complete specimen in 1750, as he mentions the figures in the

older authors, such as Willughby, and remarks, “ As none of these were satisfactory to me, I have given this

figure and description of a perfect bird, which may more than answer the purposes o f so ma n y a n d

again :— “ It hath legs and feet o f a moderate proportion and strength for its bigness, shaped much like those

o f Pyes or Jays, o f a dark brown colour, armed with claws o f middling strength.” The fact remains, however,

that the vast majority o f skins received in Europe before Mr. Wallace’s expedition, were mutilated and

footless. He writes:— “ The native mode o f preserving them is to cut off the wings and feet, and then skin

the body up to the beak, taking out the skulls. A stout stick is then run up through the specimen, coming

out at the mouth. Round this some leaves are stuffed, and the whole is wrapped up in a palm-spathe and

dried in the smoky hut. By this plan the head, which is really large, is shrunk up almost to nothing, the

body is much reduced and shortened, and the greatest prominence is given to the flowing plumage. Some

of these native skins are very clean, and often have wings and feet left o n ; others are dreadfully stained with

smoke; and all give a most erroneous idea o f the proportions of the living bird.” The following notes on