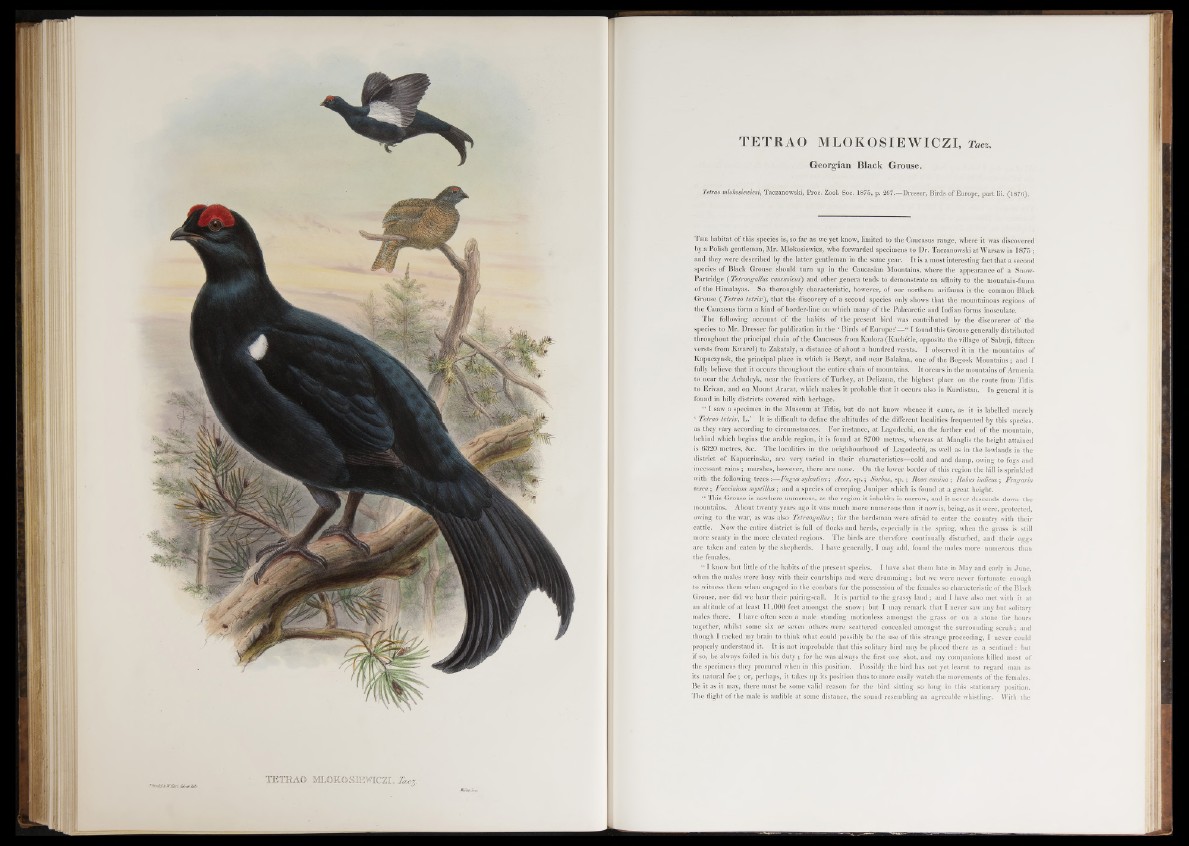

XETRAO MLOKOSIEWICZI. T a c a .

TETRAO MLOKOSIEWICZI , Tac%.

Georgian Black Grouse.

Tetrao mlokosiewiczi, Taczanowski, Proc. Zool. Soc. 1875, p. 267.—Dresser, Birds of Europe, part lii. (1876).

T h e habitat o f this species is, so far as we yet know, limited to the Caucasus range, where it was discovered

by a Polish gentleman, Mr. Mlokosiewicz, who forwarded specimens to Dr. Taczanowski at Warsaw in 1875 ;

and they were described by the latter gentleman in the same year. It is a most interesting fact that a second

species of Black Grouse should turn up in the Caucasian Mountains, where the appearance o f a Suow-

Partridge ( Tetraogallus caucasicus) and other genera tends to demonstrate an affinity to the mountain-fauna

of the Himalayas. So thoroughly characteristic, however, of our northern avifauna is the common Black

Grouse ( Tetrao tetrix), that the discovery of a second Species oniy shows that the mountainous regions of

the Caucasus form a kind of border-line on which many of the Palaearctic and Indian forms inosculate.

The following account o f the habits of the present bird was contributed by the discoverer of the

species to Mr. Dresser for publication in the ‘ Birds of Europe:’—■“ I found this Grouse generally distributed

throughout the principal chain of the Caucasus from Kadora (Kachetie, opposite the village of Sabuji, fifteen

versts from Kwarel) to Zakataly, a distance of about a hundred versts. I observed it in the mountains of

Kapuczynsk,.the principal place in which is Bezyt, and near Balakna, one o f the Bogosk Mountains; and I

fully believe that it occurs throughout the entire chain of mountains. It occurs in the mountains o f Armenia

to near the Achalcyk, near the frontiers of Turkey, at Delizana, the highest place on the route from Tiflis

to Erivan, and on Mount Ararat, which makes it probable that it occurs also in Kurdistan. In general it is

found in hilly districts covered with herbage.

“ I saw a specimen in the Museum at Tiflis, but do not know whence it came, as it is labelled merely

‘ Tetrao tetrix, L.’ It is difficult to define the altitudes of the different localities frequented by this species,

as they vary according to circumstances. For instance, at Lagodechi, on the further end o f the mountain,

behind which begins the arable region, it is found at 8700 metres, whereas at Manglis the height attained

is 6320 metres, &c. The localities in the neighbourhood o f Lagodechi, as well as in the lowlands in the

district of Kapucrinske, are very varied in their characteristics—cold and and damp, owing to fogs and

incessant rains ; marshes, however, there are none. On the lower border of this region the hill is sprinkled

with the following trees:— Fagus sylbatica; Acer, sp .; Sorbus, s p .; Rosa canina; Rubas iadieus ; Fragaria

vesca; Vacdnium imjstillus; and a species of creeping Juniper which is found at a great height.

“ This Grouse is nowhere nu, merous, as the region it inhabits is narrow, aud it never descends down the

mountains. About twenty years ago it was much more numerous than it now is, being, as it were, protected,

owing to the war, as was also Tetraogallus; for the herdsman were afraid to enter the country with their

cattle. Now the entire district is full of flocks and herds, especially in the spring, when the grass is still

more scanty in the more elevated regions. The birds are therefore continually disturbed, and their eggs

are taken and eaten by the shepherds. I have generally, I may add, found the males more numerous than

the females.

“ I know but little of the habits of the present species. I have shot them late in May and early in June,

when the males were busy with their courtships and were drumming; but we were never fortunate enough

to witness them when engaged in the combats for the possession of the females so characteristic o f the Black

Grouse, nor did we hear their pairing-call. It is partial to the grassy land ; and I have also met with it at

an altitude of at least 11,000 feet amongst the snow; but I may remark that I never saw any but solitary

males there. I have often seen a male standing motionless amongst the grass or on a stone for hours

together, whilst some six or seven others were scattered concealed amongst the surrounding scrub; and

though I racked my brain to think what could possibly be the use of this strange proceeding, I never could

properly understand it. It is not improbable that this solitary bird may be placed there as a sentinel: but

if so, he always failed in his duty; for he was always the first one shot, and my companions killed most of

the specimens they procured when in this position. Possibly the bird has not yet learnt to regard man as

its natural fo e ; or, perhaps, it takes up its position thus to more easily watch the movements of the females.

Be it as it tnay, there must be some valid reason for the bird sitting so long in this stationary position.

The flight of the male is audible at some distance, the sound resembling an agreeable whistling. With the