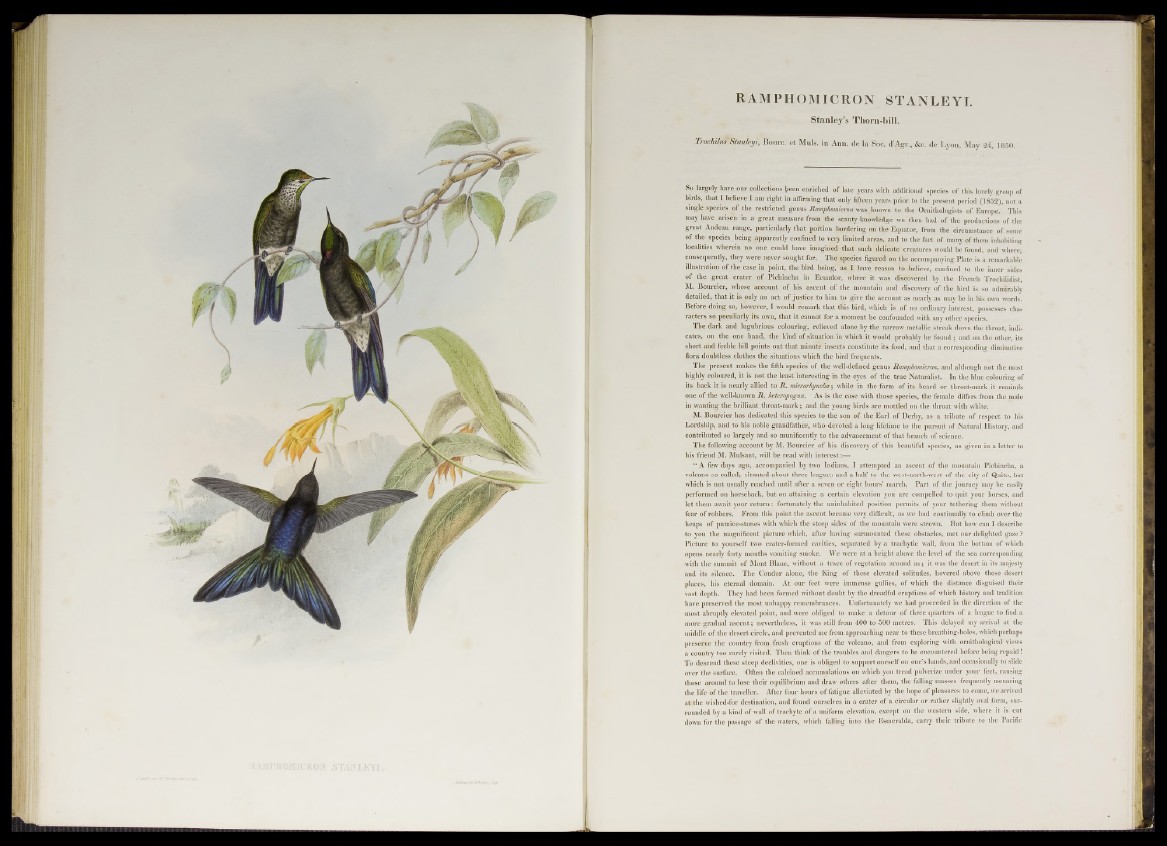

RAMPHOMICRON STANLEYI.

Stanley’s Thorn-bill.

Trochilus Stanleyij Bourc. et Muls. in Ann. de la Soc. d’Agr., &c. de Lyon, May 24, 1850.

So largely have our collections fceen enriched of late years with additional species of this lovely group of

birds, that I believe I am right in affirming that only fifteen years prior to the present period (1852), not a

single species of the restricted genus Rmnphomicron was known to the Ornithologists of Europe. This

may have arisen in a great measure from the scanty knowledge we then had of the productions of the

great Andean range, particularly that portion bordering on the Equator, from the circumstance of some

of the species being apparently confined to very limited areas, and to the fact of many of them inhabiting

localities wherein no one could have imagined that such delicate creatures would be found, and where,

consequently, they were never sought for. The species figured on the accompanying Plate is a remarkable

illustration of the case in point, the bird being, as I have reason to believe, confined to the inner sides

of the great crater of Pichincha in Ecuador, where it was discovered by the French Trochilidist,

M. Bourcier, whose account of his ascent of the mountain and discovery of the bird is so admirably

detailed, that it is only an act of justice to him to give the account as nearly as may be in his own words.

Before doing so, however, I would remark that this bird, which is of no ordinary interest, possesses characters

so peculiarly its own, that it cannot for a moment be confounded with any other species.

The dark and lugubrious colouring, relieved alone by the narrow metallic streak down the throat, indicates,

on the one hand, the kind of situation in which it would probably be found ; and on the other, its

short-and feeble bill points out that minute insects constitute its food, and that a corresponding diminutive

flora doubtless clothes the situations which the bird frequents.

The present makes the fifth species of the well-defined genus Ramphomicron, and although not the most

highly coloured, it is not the least interesting in the eyes of the true Naturalist. In the blue colouring of

its back it is nearly allied to R» ttitcroThytichci, while m the form of its heard or throat-mark it reminds

one of the well-known R. heteropogon. As is the case with those species, the female differs from the male

in wanting the brilliant throat-mark; and the young birds are mottled on the throat with white.

M. Bourcier has dedicated this species to the son of the Earl of Derby, as a tribute of respect to his

Lordship, and to his noble grandfather, who devoted a long lifetime to the pursuit of Natural History, and

contributed so largely and so munificently to the advancement of that branch of science.

The following account by M. Bourcier of his discovery of this beautiful species, as given in a letter to

his friend M. Mulsant, will be read with interest:—

“ A few days ago, accompanied by two Indians, I attempted an ascent of the mountain Pichincha, a

volcano so called, situated about three leagues and a half to the west-north-west of the city of Quito, but

which is not usually reached until after a seven or eight hours’ march. Part of the journey may be easily

performed on horseback, but on attaining a certain elevation you are compelled to quit your horses, and

let them await your return: fortunately the uninhabited position permits of your tethering them without

fear of robbers. From this point the ascent became very difficult, as we had continually to climb over the

heaps of pumice-stones with which the steep sides of the mountain were strewn. But how can I describe

to you the magnificent picture which, after having surmounted these obstacles, met our delighted gaze ?

Picture to yourself two crater-formed cavities, separated by a trachytic wall, from the bottom of which

opens nearly forty mouths vomiting smoke. We were at a height above the level of the sea corresponding

with the summit of Mont Blanc, without a trace of vegetation around us; it was the desert in its majesty

and its silence. The Condor alone, the King of these elevated solitudes, hovered above these desert

places, his eternal domain. At our feet were immense gullies, of which the distance disguised their

vast depth. They had been formed without doubt by the dreadful eruptions of which history and tradition

have preserved the most unhappy remembrances. Unfortunately we had proceeded in the direction of the

most abruptly elevated point, and were obliged to make a detour of three quarters of a league to find a

more gradual ascent; nevertheless, it was still from 400 to 500 metres. This delayed my arrival at the

middle of the desert circle, and prevented me from approaching near to these breathing-holes, which perhaps

preserve the country from fresh eruptions of the volcano, and from exploring with ornithological views

a country too rarely visited. Then think of the troubles and dangers to be encountered before being repaid!

To descend these steep declivities, one is obliged to support oneself on one’s hands, and occasionally to slide

over the surface. Often the calcined accumulations on which you tread pulverize under your feet, causing

those around to lose their equilibrium and draw others after them, the falling masses frequently menacing

the life of the traveller. After four hours of fatigue alleviated by the hope of pleasures to come, we arrived

at the wished-for destination, and found ourselves in a crater of a circular or rather slightly oval form, surrounded

by a kind of wall of trachyte of a uniform elevation, except on the western side, where it is cut

down for the passage of the waters, which falling into the Esmeralda, carry their tribute to the Pacific